(KIRAN KRISHNA SHRESTHA)

Our 4WD juddered over pits and bumps on the untarmaced road up the hillside to Mai Pokhari. Our driver took each twist with bravado. Some of us hung on to our seats, but young conservationist Kamal Rai, oblivious to the dangers and dropping temperature, was enthusiastically pointing out the flowering apple and plum trees by the wayside.

The ride was forgotten a few minutes later as we stood looking at the dark green forest reflected serenely in the lake. Rai, though, was just warming up to his job. He was quick to point out exotic fish in the lake, left behind by British Army folks. These (the fish, not British Army personnel), now indiscriminately gobble up eggs of a rare salamander species found only in this region.

|

|

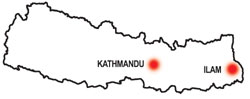

This part of the massive eastern Himalaya, ranging across spread across Ilam, Panchthar, and Taplejung in east Nepal, northeast India, and Bhutan, is less-studied and understood than other biodiverse regions of the country like the tarai and Khumbu. It even looks mysterious, with its hidden valleys and impenetrable forest clouded with mist, dripping richly with moisture all year round. The green is broken by thick clumps of scarlet and white rhododendron and still unidentified orchids clinging to mossy trees. The foxy-bandit-like red panda and the rarely-spotted snow leopard are natives.

|

|

Because the terrain is rugged and often inaccessible, biological surveys are difficult. As a result, most of the information available is on larger vertebrates that are relatively easy to identify and observe. The smaller mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish have been neglected. The most abundant animal group here-insects-has been virtually ignored. The Kangchenjunga-Singalila forests house about 35 species of birds considered at risk.

Scientists say the true extent of the region's biodiversity is vastly underestimated. Professionally and personally, they say, it is one of the most rewarding areas to work in. Hem Sagar Baral, head of Bird Conservation Nepal, believes that his work here could also help fulfil a personal goal every birder has-to identify new species. Ethnobotanist Krishna Shrestha hopes to have luck with unidentified plants.

Sarala Khaling, co-ordinator for the grants in the eastern Himalaya, says this is just the beginning. As annual grantees become more diverse, they will help design innovative conservation efforts and strengthen the relationship between people and their environment. Khaling says she particularly hopes that local women's and media groups will join in the efforts, instead of leaving the field to Kathmandu-based organisations. There is a strong feeling out here in Ilam of possibility and hope that there are good days ahead for the area's rich, pristine environment.

Sarala Khaling, co-ordinator for the grants in the eastern Himalaya, says this is just the beginning. As annual grantees become more diverse, they will help design innovative conservation efforts and strengthen the relationship between people and their environment. Khaling says she particularly hopes that local women's and media groups will join in the efforts, instead of leaving the field to Kathmandu-based organisations. There is a strong feeling out here in Ilam of possibility and hope that there are good days ahead for the area's rich, pristine environment.

Grants were made possible by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF), a joint initiative of Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Japan, the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, and the World Bank.