Better To Have Been Killed

Produced and Directed by

Dhruba Basnet

CIJ/Himal Association 2006

[email protected]  The recurring theme in Dhruba Basnet's heartrending documentary about journalists being tortured in detention is how they asked their tormentors to just finish it off by shooting them.

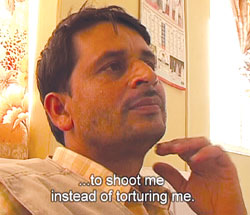

The recurring theme in Dhruba Basnet's heartrending documentary about journalists being tortured in detention is how they asked their tormentors to just finish it off by shooting them.

"It became unbearable," recalls Nagendra Upadhya of the Mallika newspaper in Dhangadi, "I just wished I could die quickly and be freed of my pain and misery."

Badri Sharma of Dhorpatan Dainik in Baglung told the police who were smashing his toe-nails: "Give me your pistol, I'll kill myself." The policeman replied: "You think you can die so easily?"

Dipin Rai of Mukti Abaj in Jhapa was tortured so brutally in a semi-underground bunker that he remembers thinking: "Wish they'd just kill me."

"I couldn't bear the torture and even thought of trying to escape so they would shoot me," says Ambika Bhandari, the Dhankuta correspondent of Nepal Samacharpatra.

Given the agonised on-camera testimonies of journalists under torture it is no surprise that Dhruba Basnet has titled his latest documentary Better To Have Been Killed. Just watching and listening to these traumatised editors is bad enough, and all of them carry the physical and psychological scars of their ordeal.

And for those who thought King Gyanendra's military regime was bad, the documentary makes a shocking revelation. The worst tortures and longest incarcerations took place when parliament was in session and elected prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba was in power in 2001-02.

The torturers during the emergency period were policemen and the journalists were blindfolded, kept inside small dark rooms with hands tied behind their backs for up to 14 months, beaten and tortured every day.

The torturers during the emergency period were policemen and the journalists were blindfolded, kept inside small dark rooms with hands tied behind their backs for up to 14 months, beaten and tortured every day.

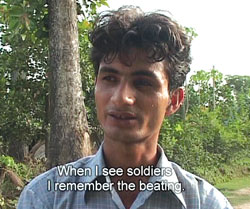

During the second emergency following the royal coup of February 2005, the torturers were soldiers and the journalists were kept in bunkers inside barracks. Before being released reporters were warned not to talk, and the testimonies show the torture was just for the sake of inflicting pain than extracting confessions.

It is a tribute to the tenacity and courage of these journalists that they not only survived, but are now coming forward to tell their tale. In his documentary, Dhruba Basnet follows the journalists as they walk back into their places of detention and show the small dark rooms where they spent nearly a year-and-half.

While Badri Sharma was being mercilessly beaten in prison, the policemen told him to quit journalism. He recalls telling them: "If by leaving journalism it will bring peace back to this country, I will quit." That is the only time he gave anything to the police.

Nagendra Upadhya was arrested because the Maoists had forced him to take a sick comrade to hospital and he was caught by the soldiers. During torture the army often told him he would be buried alive or dropped into the jungle from a helicopter.

More than a year after being released, Nagendra breaks into cold sweat and has nightmares every time he sees soldiers, he has nightmares and wakes up screaming. Badri still feels a dull pain in his stomach where the policemen kicked him with boots. Dipin looks away every time he passes the barrack where he was tortured. Ambika avoids going back to his home town of Dhankuta, there are just too many painful memories.

Shyam Shrestha, editor of Mulyankan was also stopped at the airport and detained by police during the Deuba regime in 2001 and says the only reason he was released was because of his high profile. "There was no warrant, no proof, no reason to arrest us, in hindsight it is clear this was a dress rehearsal for the royal coup," he says.

In 2002, the international press watchdog, Reporters without Borders accused Deuba of 'turning Nepal into the world's biggest prison for journalists'. The known torturers of journalists are still in the police and army, they were ever tried.

Ambika Bhandari was the only journalist who took the police and government to court and was awarded Rs 20,000 by the Dhankuta court. The government has appealed the case.

Operation Free Voice

Operation Free Voice

Producer and Director

Hasta Gurung

CIJ/Himal Association, 2006

[email protected]

Hasta Gurung's documentary is a chronology of the crackdown on the media after the February 2005 military coup by the king. Overnight, newsrooms were turned into barracks, there was direct censorship and FM stations were not allowed to broadcast news.

Operation Free Voice documents the stories of the journalists in the frontlines, how they struggled to uphold their freedom, defied controls and then used media's power to restore democracy.

The army singled out radio for special treatment, confiscating transmitters, harassing radio reporters, threatening to take away their licenses. The Supreme Court through numerous verdicts and stay orders came out strongly in support for free press and giving radio stations the legal basis to start re-broadcasting news.

The army singled out radio for special treatment, confiscating transmitters, harassing radio reporters, threatening to take away their licenses. The Supreme Court through numerous verdicts and stay orders came out strongly in support for free press and giving radio stations the legal basis to start re-broadcasting news.

Hasta Gurung also tells the story of how the Maoists ransacked Radio Ghodaghodi in Banke that broadcast in Tharu language. Far from apologising, Maoist leader Min Bahadur Sob is shown publicly warning stations they will be attacked if they persisted in their "anti-people" broadcasts.

The radio stations did not sit idly by, they resisted and defied controls, mailed a broken radio set to Information Minister Tanka Dhakal, organised a nationwide referendum on whether news should be allowed on FM, held protest poetry readings, concerts and parody shows, they read the news to passers-by on the streets and even sang the news.

The lesson of Operation Free Voice is that the media successfully fended off controls only because it was united. Nepal's media showed that the best way to safeguard press freedom is by its maximum application.

I am a Nepali-Hear My Voice

Produced by Heart in Design

UNESCO Nepal and OHCHR, 2007  If you thought press freedom was only for media, this UN-produced film shatters that myth. Access to information is a fundamental right of citizens, not just of journalists. It uses the example of Madan Pokhara FM and Lumbini FM to show how information empowers people and liberates them.

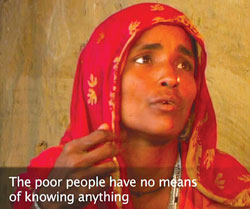

If you thought press freedom was only for media, this UN-produced film shatters that myth. Access to information is a fundamental right of citizens, not just of journalists. It uses the example of Madan Pokhara FM and Lumbini FM to show how information empowers people and liberates them.

Yet, despite the spread of FM radio throughout Nepal, there are still large areas which do not have easy access to information. The digital divide exists not just globally but within Nepal, where the spread of information is uneven. New technologies, if judiciously used, can help us leapfrog the gap.

Asked about whether she finds radios useful, a woman Kamaiya replies matter-of-factly: "First food, then shelter, then we will think about radio."

The film underlines the challenge ahead for FM stations in Nepal: that a large section of Nepalis do not even speak Nepali. Access to information is all very well, but it has to be in a language that people understand. And then the real role for radio in the coming year, which is to educate citizens about the constituent assembly elections so that they can vote wisely.