|

|

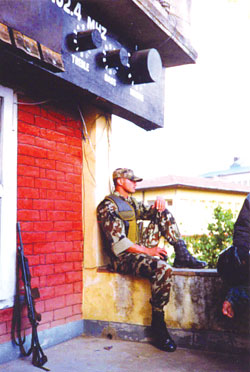

| WAR AND PEACE: Radio Sagarmatha has seen a lot in its 10 years, from soldiers occupying it after the royal coup in 2005 to being a true public broadcaster battling commercialisation in peacetime. |

Most young radio journalists today probably don't know what a long and hard battle it was ten years ago to liberate Nepal's air waves and to create public space for radio.

When Radio Sagarmatha was finally granted a license to be Nepal's first non-government radio station in May 1997 it was a milestone not just for Nepal but the whole South Asian region. The day 102.4 FM went on air was the day the government monopoly of radio ended and frequencies were recognised as public property.

Sagarmatha opened the gates to dozens of community FM stations, private commercial radio and public broadcasters. Ten years later, there are 66 independent stations through Nepal, 27 more are going on air within two months and dozens more licesense have been given out.

"Sagarmatha was a hard-won group effort, it took years of lobbying," recalls Bharat Koirala the media trainer and activist who was given the Magsaysay Award in 2000 for his contribution. Koirala's original idea was to turn Sagarmatha into a nucleus for training community broadcasters throughout Nepal, and use grassroots communications to empower rural Nepal and help development.

But even after the license was granted to the Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists (NEFEJ) to run Sagarmatha, there were numerous hurdles: fixing the tax for public broadcasters, distinguish between community and commercial stations and finding a legislative framework.

"In April 1997, we sent a letter to the Ministry of Communication asking for a permission to test broadcast," recalls present station manager Mohan Bista, "the government didn't respond so we went ahead and broadcast anyway."

|

|

Getting Sagarmatha on air was instrumental in creating awareness that community radios could expand the public sphere creating the conditions for democracy and development to thrive. But it hasn't all gone according to plan. The virtually unregulated process has brought with it commercial pressures on the quality of programming. Many private stations, dependent on advertisement support, cater to young, urban, middle class people with high purchasing power.

Nepal needs public broadcasters, doing inclusive and participatory programming, to supply rural communities with access to relevant information. These programs being information-based have higher running costs and lower advertisement revenues than commercial stations.

Forced to pay 4 percent tax on income and a high annual broadcasting royalty, community stations including Radio Sagarmatha find it hard to sustain themselves. So it depends on donor support, partnerships and sponsored programming.

In July 2001 a landmark Supreme Court decision assured broadcasters the same freedoms as those available to print media and ruled that a ban on news restricted the constitutional right to information. But broadcasters have faced constant harassment and restrictions culminating in a blanket ban on news on radio after the royal coup of Feburary 2005.

In November that year police raided Sagarmatha, seized equipment and took five journalists into custody for a BBC interview with Pushpa Kamal Dahal. The fact that the station hadn\'t actually run the interview wasn\'t considered. Sagarmatha took the case to the Supreme Court which ruled that BBC rebroadcasts should be allowed on FM. Sagarmatha had won this victory on behalf of a dozen other stations that also relay the BBC Nepali Service.

FM in Nepal is now no longer a development project, thanks to Sagarmatha's pioneering work, it is a mainstream phenomenon that has contributed to the creation of public space. "Now we are facing the second generation problems, monitoring, regulation and the setting of quality standards being the most urgent," says Binod Bhattarai of the Centre for Investigative Journalism who was station manager in 1998-99. Licensing should become more transparent and differentiate between non-profit and commercial broadcasters and handled by an independent monitoring authority, he adds.

To achieve this the government should step back from being the monitoring, licensing and broadcasting agency at the same time. It should take the role as a regulator in the public interest and guarantee the survival of public broadcasters and institutions like Sagarmatha that try to promote this. Licensing and regulation should itself be decentralised.

Radios have given voice to indigenous groups and neglected languages, but it has a long way to go in ensuring ethnic and gender diversity in staffing.

Raghu Mainali of the Community Radio Support Center (CRSC), says: "Sagarmatha has helped community radios throughout Nepal with training now we need to work together to improve the quality, participatory nature of programming and ensuring sustainability."