|

|

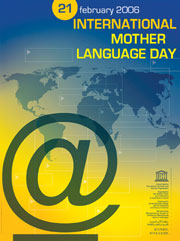

International Mother Language Day on 21 February has particular resonance for South Asia. On that day in 1952, a number of Bangladeshi language activists were shot and killed by police as they demonstrated for Bengali language rights.

Established at the 1999 UNESCO General Conference, and first celebrated in February 2000, International Mother Language Day (IMLD for short) was established to promote linguistic diversity and multilingualism. In 2005, IMLD was devoted to Braille and sign languages, last year's topic was languages and cyberspace, and this year the theme is very pertinent to Nepal: the links between mother tongues and multilingualism.

UNESCO states unequivocally on its website that "all moves to promote the dissemination of mother tongues will serve not only to encourage linguistic diversity and multilingual education but also to develop fuller awareness of linguistic and cultural traditions throughout the world and to inspire solidarity based on understanding, tolerance, and dialogue." While honourable and even noble, this suggestion remains contentious. In Nepal, language policy and linguistic rights are thorny political issues, and recent statements by language activists show a tendency towards isolationism, exceptionalism, and division in the name of inclusion and participation.

Even the United States and the United Kingdom, two nations held together by so much cultural background and shared history, are said to be divided by a common language. What about Nepal and its close to 100 languages? What implications does International Mother Language Day have for this nation in transition, and how should it be celebrated?

|

|

A helpful point of departure for understanding the emotional attachment to mother tongues in Nepal is the constitution, particularly because the ground has recently shifted. While Article 4 of Part 1 of the 1990 constitution declared Nepal to be multi-ethnic and multi-lingual, Article 6 stated that the Nepali language in the Devanagari script would be the official language of the nation. Almost as a concession, all the remaining languages spoken as mother tongues across the then kingdom were declared 'national languages of Nepal'.

The recently promulgated interim constitution makes a small but significant compromise on the issue of language: even though the Nepali language in the Devanagari script retains its place as the official language, all mother tongues spoken in Nepal are to be regarded as languages of the nation, and may be used in local administration and offices. The responsibility of translating from these indigenous mother tongues into Nepali for public records falls to the government.

The symbolic importance of these changes is considerable, as the topic is deeply emotive for many Nepalis whose mother tongue is not Nepali. But it is too early to say whether they will make any practical difference to the lives of non-Nepali speakers.

|

|

| Educating Babel: While studies show that students learn better through their mother tongue, the language has to be taught in school for the benefits to be reaped, which is rarely the case with minority languages. |

On the other hand, speakers of minority languages have real contemporary and historical grievances, and been met with opposition at all levels when they've tried to implement the rights granted to them in the constitution. Non-Nepali speaking, non-caste Hindu ethnic groups have long felt excluded from full participation and recognition in the state by a homogenous vision of what it means to be Nepali. What better time than now, they argue, while the Nepali nation is taking its new shape, to voice their frustrations and redress those wrongs.

Part of the difficulty for Nepal is that much of the groundwork needed for formulating a robust, progressive language policy is lacking. Linguists still disagree about the number of languages spoken in the country, let alone dialects, and a comprehensive linguistic survey has yet to be conducted. Historically, the decadal census of Nepal has oscillated on whether it was counting discrete languages or ethnic groups, and only more recently have bhasa and jat been enumerated as distinct categories.

The gap between practical action and symbolic language policy in Nepal is steadily growing. On the practical side, we learnt on 1 February, a project called Newa Schools in Newa Settlements (NSNS) will fund the establishment and operation of two Newar language schools in which the medium of instruction is Newa Bhae.

This is excellent news, and in line with international best practices and UNESCO recommendations on primary education. On the symbolic side, it was announced on the same day that the interim constitution is being translated into a number of 'indigenous' languages, an effort more rhetorical than useful. How will phrases such as 'constituent assembly' be translated into Magar, and how many Chamling or Tharu speakers will actually read the document in their mother tongue?

This is excellent news, and in line with international best practices and UNESCO recommendations on primary education. On the symbolic side, it was announced on the same day that the interim constitution is being translated into a number of 'indigenous' languages, an effort more rhetorical than useful. How will phrases such as 'constituent assembly' be translated into Magar, and how many Chamling or Tharu speakers will actually read the document in their mother tongue?

Amid all the posturing, there is little discussion of a more fundamental question: what makes a language indigenous to Nepal? In the Nepali context, the claim to indigenousness is more about disadvantage than about being autochthonous or adivasi. When language activists say Nepali is not an indigenous language of Nepal (where is it indigenous to, then?), they are making a claim about oppression and inclusion, not about nativity. Likewise, when janajati rights campaigners invoke history and territory to make claims of indigenousness, they forget that the arrival of many well-known 'janajati' communities like the Sherpa far post-dates the settlement of Bahun and Chhetri 'migrants' into Nepal's middle hills.

Claims for ethno-linguistic autonomy need to be carefully balanced with an appreciation of the inherently heterogeneous and multilingual nature of modern Nepal. The map (see above) can easily be misinterpreted as suggesting that only Newa Bhae is spoken in Kathmandu, or that one unified language called Bhote is spoken across Nepal's northern border from the far-west to the central regions, when in fact no such language exists. The reality is much more complex, with layers of languages and mixtures of various peoples occupying most of Nepal's landmass. Truly homogenous regions are few and far between, and not representative of the diversity of most areas.

Nepal is now at another crossroads in its turbulent history. Much is up for debate and negotiation, and members of communities who have been historically marginalised have legitimate aspirations and high hopes for a more 'inclusive' nation. Making flexible, lasting policies that genuinely support all of Nepal's languages will require foresight. Care should be taken to avoid replacing the divisive 'one nation, one culture, one language' rhetoric of the past with an equally divisive discourse of linguistic fragmentation.

Mark Turin is a linguistic anthropologist and director of the Digital Himalaya Project. He is presently fieldwork coordinator for the Chintang and Puma Documentation Project at Tribhuvan University.