There are many criticisms to be made of Washington's response to the heinous attacks of 11 September 2001. Much depends on the political and cultural proclivities of the critic, whether he or she is an Islamist or a neo-conservative, a leftist or a liberal.

There are many criticisms to be made of Washington's response to the heinous attacks of 11 September 2001. Much depends on the political and cultural proclivities of the critic, whether he or she is an Islamist or a neo-conservative, a leftist or a liberal.

But there's little disagreement with one point made by the high-level commission tasked with finding out why the attacks on America succeeded. In its report released in 2005, the 9/11 commission singles out "groupthink". This, in the words of commission co-chair Lee Hamilton, was to blame for intelligence agencies and policy makers failing to anticipate the plot to crash civilian airliners into high profile targets.

Similarly, a US Senate probe into why Weapons of Mass Destruction weren't found in Iraq after the invasion of 2003 blamed groupthink among those who were analyzing the intelligence data. So intent were the White House and its proxies on attacking Iraq, the report says, that even sober analysts pushed the notion that Saddam Hussein was armed to the teeth with nukes, biological bombs, and nerve gas. That these were lies and fallacies we now know all too well.

The idea of groupthink isn't new. The term was coined by the American writer and individual thinker, William H Whyte, in 1952. His definition is still the best.

Groupthink, he writes, is "a rationalised conformity-an open, articulate philosophy which holds that group values are not only expedient, but right and good as well." This, he concludes witheringly, is "a perennial failing of mankind."

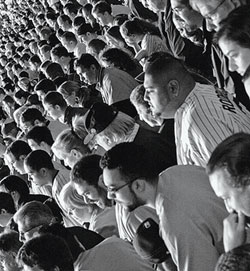

In other words, we are part of a group that is working on a series of tasks or challenges and we already agree on many things. So that informs what we do, how we try to achieve our outcome, how we view the world. It matters more than the solution to the problem. Groupthink is in our nature as social beings who crave acceptance into something larger than just ourselves and our immediate family.

It's part of being intellectually lazy, which many of us are. It's innate, part of us, hardwired into our flawed human brains. So Osama Bin Laden won't attack America. Saddam is a threat and Afghanistan doesn't matter. There's no civil war in Iraq and the tarai and janajatis will just trust us. We'll be kind to the women and dalits too, just be patient.

It is-admittedly-grossly unfair to blame just the interim government of the moment for having the monopoly on groupthink in Nepal. There's plenty scattered over the detritus of recent history. King Gyanendra and his cohorts positively reeked of it. How else could ministers, military officer, and courtiers keep taking over a country that they already ran.Throughout the 1990s, freedom fighters turned democrats thought blithely and blindly that everything was wonderful while the Maoists raised the ire of the hills to revolutionary pitch. The entire Panchayat era was the most egregious example of Whyte's "perennial failing" that South Asia had to offer. The least said about Rana times the better.

These days, the bitter fruits of generations of groupthink are falling ever more rapidly from the tree and yet there are hopeful signs that Nepal is shaking off the demons of collective thought. The new voices in parliament, whether Maoist, civil society, madhesi, women, or excluded castes, will be immune in the short term to the urge to conform to discredited ideas. Democratic feudalism or high caste turf defending, neither will move these new groups to think as elites demand.

The key is to keep the group open and expanding. To resist the urge to slam shut the gates of inclusion once your group is inside. That's certainly tempting.

Comfort rests in familiarity. But I'm confident that Nepal's new dynamic is unstoppable, however unpredictable and inconvenient.

Someone call Washington. Here's a little something that they could learn from Kathmandu.