The ambitious project to bring Himalayan glacial melt through a tunnel to augment the Valley's water supply is already seven years late, but it may be delayed further. Demand for water has far outstripped supply, and this dry season will see massive shortages.

The ambitious project to bring Himalayan glacial melt through a tunnel to augment the Valley's water supply is already seven years late, but it may be delayed further. Demand for water has far outstripped supply, and this dry season will see massive shortages.

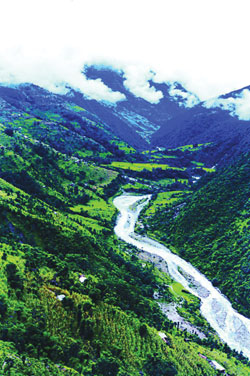

The road to the Melamchi headworks(pictured) in Sindupalchok is almost complete. But before the 26.5km tunnel drilling can start, the government has to fulfil the condition of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to revise water distribution policy.

In January, the now-dissolved parliament passed a bill amending the Nepal Water Supply Corporation Act which terminated its control of the Valley's water supply system and brought in the British firm, Severn Trent Water, as a management contractor.

NWSC employees cut off water supply to Singha Darbar, Baluwatar and the royal palace in protest.

The ADB had wanted a Water Regulatory Board, Tariff Fixation Commission and the setting up of a private Kathmandu Water Limited (KWL). The conditions have been met. And when three other bidders withdrew, Severn Trent bagged the contract to manage the capital's water supply for six years for a total of

$8.5 million.

The reason for the present hurry seems to be that the ADB is reviewing its Melamchi loan in March, and this has stiffened political opposition to the deal.

"The government says Kathmandu's water distribution is not managed well, but why do we need a foreign company without any competition?" asks Prakash Rai, of the NC-D affiliated employees association still staging a sit-in outside NWSC office. A rival union affiliated to the UML has agreed to government assurance that jobs will be guaranteed, but Rai says there are loopholes.

The Melamchi Water Supply Development Board (MWSDB) says privatisation doesn't mean the NWSC is being sold to a foreign company. "This is just a management contract, which means that the general, technical, and financial expertise is from a foreign company," explains the Board's Poorna Das Shrestha.

He says Nepali companies weren't qualified enough to take up the job and Severn Trent showed its commitment by staying with the bidding process despite three bidding calls. A French and German company which had been short-listed withdrew.

Privatisation has its detractors, but Shrestha says Severn Trent will guarantee two hour water supply to 190,000 taps in Kathmandu in two years even before Melamchi is completed.

Regardless of whether or not Severn Trent takes over, there will be a water tariff hike. In 2004, the government decided to increase prices annually by 15 percent. For the last two years the tariff has remained the same, which means the next increase will be a whopping 30 percent. Consumers paying Rs 50 for 10,000 litres will now have to pay Rs 66.

"Whether water can be considered a commodity is a debate in itself, but water and sanitation are public utilities. If they are to be looked after by private companies, what then is the government going to do?" asks lawyer Bhola Nath Dhungana, who has researched Manila's experience with water privatisation. In a country with a patchy history of privatisation, handing over an essential commodity like water to the private sector is fraught with risks, he says, adding that it has failed in Bolivia, Argentina, and the Philippines.

NWSC's Hari Prasad Dhakal says the state-owned company was never given a chance to prove itself. "Instead of interfering with NWSC, the government should have made it autonomous and freed it from political interference," he says.

Experts say the government has never looked at alternatives to Melamchi. Just upgrading the ageing water mains and cutting back on leakage would augment supply by anywhere between 40 to 70 percent. Cutting back on waste by pricing could conserve water, and rain-harvesting would provide water for non-drinking use. Construction of reservoirs on the Valley rim to store monsoon runoff would be much less expensive than drilling a long tunnel.

"The problem of water scarcity did not arise overnight, and we have alternative ways of bringing in water besides Melamchi," says Dhungana, "it's not too late to look at them."