|

|

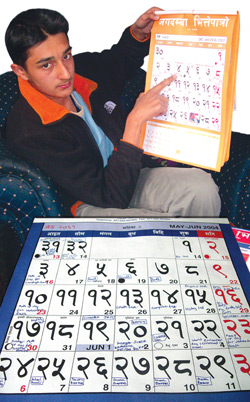

It's been over three years since 18-year-old Prajwal Raj Gyawali started marking off every school day that's been disrupted by strikes, bandas, and chakkajams. Prajwal's calendars start with the five bandas in April 2003, and go right up to the one on 23 December protesting the ambassadorial appointments. In that time, a total of 94 school days have been lost to shutdowns.

Prajwal's calendars are a telling record of the chaos of the last few years. Marked off is the 13-day educational strike that the Maoists called in June 2004 demanding for lower school fees, as well as the days that were lost in September 2004 after 11 Nepalis were killed in Iraq, and the 19-day shutdown for Jana Andolan II last April. Prajwal was in grade eight in Rato Bangala School when he started keeping track, and he's now in his first year of A levels. "I've been robbed of more than four months of school days," he notes.

For Prajwal, the project is about more than making sure there's a record of how his education has been disrupted. He's interested in the sociological and psychological reasons and consequences of shutdowns. Prajwal plans to become a lawyer-he's done a three-month internship with Pro-public-and has much to say about the way protests are carried out in Nepal. "Closing down educational institutions and resorting to vandalism to lower school fees didn't seem like a good idea to me," he says in an understatement. "When Nepal closed down for 19 days for the mass movement, I didn't feel as sad as I usually do during bandas, but it is depressing that the behaviour of politicians remains unchanged."

Prajwal is concerned that the banda mentality sticks, despite progress in the peace process. "Protest through movies, newspapers, radio, tv. Organise concerts and sing freedom songs. Ask for reasonable things through proper channels.

Why do you need a banda?" he asks.

Dambar K Shrestha