Despite millions of dollars being poured into Nepal to fight AIDS over the past decade, public health experts say the epidemic is spreading into the general population because of failure to address high-risk groups.

At the 16th International AIDS conference in Toronto this week, a World Bank report warned that unless more effective measures are taken to halt the spread of the disease by sex workers, injecting drug users, trafficked women and male migrant workers, Nepal faced a serious threat.

Nepal's own country report shows that prevention programs have been successful, as the rate of increase in infection has stabilised and the prevalence in certain high-risk groups has gone down due to targeted interventions. But despite all this, these programs are still not reaching enough HIV-infected people.

"We have not been able to halt, if not reverse, the spread of the epidemic in Nepal," says Mahesh Sharma of UNAIDS, "this is why the number of infected people has increased." The study confirms that prevention programs reach only one-third of sex workers, only 8.9 percent of injecting drug users and just 0.4 percent of migrant workers.

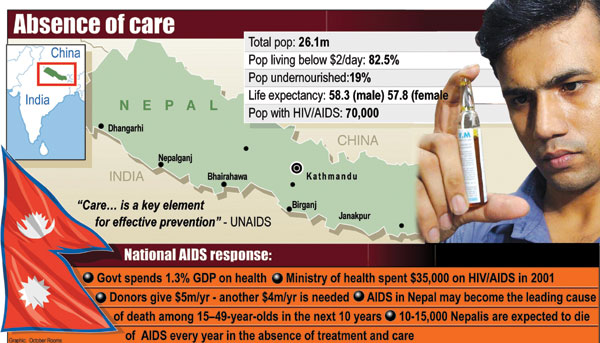

There are no accurate figures on the total number of HIV infected people in Nepal, but they are mostly in the 30-39 age group and 22 percent are women. Migrant workers make up 46 percent of those infected, 20 percent are clients of sex workers, and nearly 10 percent are injecting drug users.

Shyam Sundar Mishra, director of National Centre for AIDS and STD Control (NCASC) admits that prevention efforts are concentrated in urban areas. He says, "we need time to take it across the country because HIV/AIDS programs are fairly new."

However, anti-AIDS activists blame the government's poor policies and lack of commitment. They say AIDS is a social and development issue. "HIV/AIDS should be included in the national plan and needs to stop being treated as just a health problem," says Bhoj Raj Pokhrel, of Policy Project, Nepal.

Some blame a lack of money. The total budget for HIV programmes for 2005 was at $23 million and over half of that came from donors. However, even if more money was available experts say the country just can't spend it. "We don't have the institutional and technical capacity to absorb the money," says Bina Pokhrel at the NCASC.

Her boss Mishra argues that although we may lack the capacity to spend money for AIDS prevention, the need is great. "The money comes in just when the donor projects are phasing out, we have to implement our programs in six or seven months, which is not enough time to use all the funds," he adds.

Money has been available from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria since 2002, but approval has been stuck because the Ministry of Health was incapable of spending it. The funds, including other grants from DFID and AUSAid, are managed by the local UN office.

While all this is going on in Kathmandu, HIV is spreading to reaching remote parts of Nepal where awareness about prevention is still low. People are dying due to a lack of access to treatment. Infected people in urban areas are waiting for donors and the government to figure out a way to make anti-retroviral treatment affordable and to deliver care and support.

After much lobbying the government started providing free anti-retrovirals in 2004. But the waiting list at NCASC for the drugs is long, and patients have to sometimes wait weeks.

"We have a patient who needs the medicine, but her turn may not come for another two weeks, so she is forced to buy the anti-retrovirals to survive," says a member of Sneha Samaj, a hospice for women with HIV.

While anti-retrovirals have given infected people longer lives elsewhere, more people are dying not because of AIDS but because of society's discrimination against them.

As one patient, Sneha Samaj says, "When awareness is low, and stigmatisation is so high most patients would rather give up and die than come out."

Who gets the cure?

"When I do not have enough to eat, what do I do with the anti-retrovirals? Many in the villages don't have that luxury," says an HIV patient at Sneha Samaj. She is one of the few Nepalis with HIV whose life has been prolonged by care and support as well as anti-AIDS drugs.

Infected people want the government to give them care services, nutrition programs, rehabilitation, skills training and counselling so that they can learn to live with the disease.

Rajiv Kafle of the group Navakiran Plus disagrees. "Ideally, anti-retroviral treatment would come in a package, but we don't live in an ideal world." He is critical of donors and the government who say giving medicines is not enough. "Those pills save lives, give infected people hope and make them stronger so they can work and earn a living," Kafle adds.

Nepal's National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2002-2006 doesn't mention anti-retroviral treatment but after lobbying the government has started treating 500 people countrywide. Among donors, USAID policy is still prevention-oriented, but treatment and care has been included in the overall aim of the Global Fund. DFID has made a commitment to scale up towards universal access to treatment by 2010.