Looking back at the April Uprising and analysing media coverage of the last days of royal rule, what seems to have played a bigger role than bricks and barricades was the power of ridicule.

Looking back at the April Uprising and analysing media coverage of the last days of royal rule, what seems to have played a bigger role than bricks and barricades was the power of ridicule.

In Kirtipur, a formerly unknown student recited satirical poetry entertaining an audience of thousands for hours. Even riot police within earshot burst into laughter at the mockery of monarchy. Elsewhere, a student did impersonations of the king imitating his regal gestures and was greeted by gales of laughter.

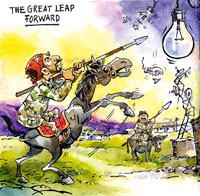

And then there were the cartoonists. Every day, as the palace dug itself deeper and deeper into a hole of its own making, the illustrations got more and more daring. A cartoonist depicted the king burying his head in the sand with his crown next to him, or showed him sawing off one of the legs of his own throne.

It was risky because lese majeste laws were still in place and punishment was harsh. But cartoonists became more and more defiant, caricaturing the king's face, his wrap-around shades, jowls and a frowning visage.

Although Batsyayana did not directly depict King Gyanendra his cartoons on the front pages of Kantipur and Kathmandu Post his cartoons lampooned a morally bankrupt regime and helped bring it down. One of Batsyayana's memorable drawings from last year is of a soldier escorting an underfed and near-naked farmer carrying a Rolls Royce into the royal palace.

Although Batsyayana did not directly depict King Gyanendra his cartoons on the front pages of Kantipur and Kathmandu Post his cartoons lampooned a morally bankrupt regime and helped bring it down. One of Batsyayana's memorable drawings from last year is of a soldier escorting an underfed and near-naked farmer carrying a Rolls Royce into the royal palace.

Because he is so famous, Batsyayana doesn't have to prove himself and be overtly contemptuous-his subtlest cartoons are his most scathing. He sets aside his sharpest barbs for sycophants, yes-men, opportunists and hyprocrites that infested post-1990 Nepal, the ones who through lust and greed squandered the gains of the 1990 People's Movement and thus set the stage for the conflict.

With his prominent proboscis Girija Koirala seems to be Batsyayana's favourite cartoon character, Madhab Nepal is a close second with his Charlie Chaplin moustache and owlish spectacles. With Sher Bahadur Deuba it is his permanently smug smirk. Batsyayan tears apart Koirala's arrogance and tolerance of corruption, Nepal's flip-flopping and Deuba's shameless kowtowing of the king and his army. His biting cartoons attack the Maoists' cynical justification of violence for political end.

Batsyayana's real name is Durga Baral and he never started out being a cartoonist, he is a painter. Living in Pokhara, he kept an eye on the shenanigans of the capital from a perspective that the people of Kathmandu lacked. What he saw was so funny, he just had to make fun of it.

Baral's son Ajit has compiled his father's best cartoons of post-1990 Nepal in this elegant volume and writes in his preface: 'We want this book to be a sustained visual history, warts and all, of post-1990 Nepal.' The book went to press in March 2006 and includes some cartoons from the post-February First period of censorship. But mostly it reminds us of the hope and hopelessness of the past 15 years of Nepali history: a sobering reminder to the same politicians who came to power after People Power II not to make the same mistakes again.

Last year, at the height of royal rule and the republic vs monarchy debate, Bastsyayana's famous cartoon of Koirala carrying away a horse's corpse labelled 'constitutional monarchy' (above) appeared on the front page of Kantipur. The paper got threatening calls and the minister of information vowed to take action. The government mouthpiece Gorkhapatra wrote a scathing editorial and the king's henchmen even asked for the death penalty against the cartoonist.

The fact that Batsyayana's cartoon of Girija and the dead horse is more relevant today than it was a year ago goes to prove just how prescient and timeless his drawings are.

For that reason alone, this book which is being launched on Sunday 25 June is a must-have.

KUNDA DIXIT

Batsyayana & his barbs

Batsyayana & his barbs

A Cartoonists's Take on

Post-1990 Nepal

FinePrint, Kathmandu 2006

148 pages

Rs 700