|

|

The tub full of leeches sat on a table in Mark Siddall's office at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The leeches, each about five cm long and covered in orange polka dots, were swimming lazily through the water.

One leech suddenly began undulating up and down in graceful curves, pushing water along its body so that it could draw more oxygen into its skin.

"This is beautiful. Look at that," Dr Siddall said. "It's a very complex behaviour. The only other animals that swim in a vertical undulating pattern are whales and seals."

For Dr Siddall, leeches are a source of pride, obsession and fascination. His walls are covered in leech photographs. He owns a giant antique papier-m?ch? model of a leech, with a lid that opens to reveal filigrees of blood vessels and nerves. His lab is filled with jars full of leeches that he has collected from some of the most dangerous places in the world.

He considers the risks well worth it because he can now reconstruct the evolutionary history of leeches-how an ordinary worm hundreds of millions of years ago gave rise to sophisticated bloodsuckers.

As a boy growing up in Canada, Dr Siddall was disgusted by the leeches that attacked him when he went swimming in forest ponds. But their biology began to intrigue him as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, where he became interested in how leeches spread parasites among frogs and fishes.

"It was hard for family conversations," he said. "You couldn't exactly talk about it over Thanksgiving dinner."

By the time Dr Siddall joined the museum in 1999, the evolution of leeches had become his chief obsession.

|

| THE BITE |

To chart the leech's entire evolutionary tree, Dr Siddall had to obtain species from all of its major branches. That required a series of expeditions to places like South Africa, Madagascar, French Guyana, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, where Dr Siddall and his colleagues took off their shoes, rolled up their pants and waded into the water.

"You can't set traps for leeches," Dr Siddall said. "We are always the bait."

His research has shown that the ancestors of leeches were probably freshwater worms that fed on the surface of fish or crustaceans, as the closest living relatives of leeches do.

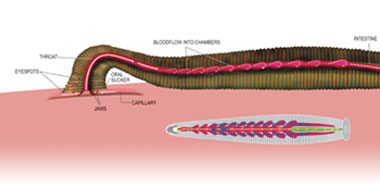

Dr Siddall has identified several major innovations that early leeches evolved as they became blood feeders. They acquired a proboscis that they could push into their hosts to drink blood. Later, some leeches evolved a set of three jaws to rasp the skin.

Leeches also needed chemicals that could keep their host's blood thin so that it would not clot in their bodies. They have evolved many molecules for that purpose, along with others that prevent inflammation. Pharmaceutical companies have isolated some of these molecules and sell them as anticoagulants.

The leeches in the tub in his lab, Dr Siddall explained, belong to the species Macrobdella decora, the North American medicinal leech. Dr Siddall has been making a careful study of North American medicinal leeches for years.

But the biggest surprise came when he applied new DNA sequencing techniques to the best-known leech of all, the European medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis.

In ancient Rome, physicians used that species to treat maladies like headaches and obesity. The tradition continued for 2,000 years.

Although physicians no longer bleed their patients, Hirudo medicinalis has been enjoying a renaissance. Surgeons reattaching fingers and ears find that patients heal faster with the help of leeches. By injecting anticoagulants, leeches increase the flow through the reconnected blood vessels.

When Dr Siddall and Peter Trontelj of the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia analysed the DNA of the European leech, they received a big surprise. "The European medicinal leech is not one species at all," Dr Siddall said. "It's at least three."

The researchers are now trying to determine the abilities among the three species and their differences. More important, they hope that their work will draw attention to the plight of European leeches. Over-harvesting and habitat destruction have cut their numbers drastically.

Dr Siddall knows that the notion of leech conservation may seem odd to some people. But he points out how many medical surprises leeches have yielded. New species will presumably yield new surprises. But he also thinks people should be concerned about leeches simply because they are leeches.

"Don't you think the world would be a colder, darker place without leeches?" he asked. He raised his tub with a smile. "Especially ones with orange polka dots?" (NYT)