When Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher abolished slavery he used money from Pashupatinath to compensate slave owners. Indeed, the temple, perhaps one of Nepal's largest landowners, could still be a last resort today in times of national need.

When Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher abolished slavery he used money from Pashupatinath to compensate slave owners. Indeed, the temple, perhaps one of Nepal's largest landowners, could still be a last resort today in times of national need.

King Girbanaya Yuddha Bikram Shah gave 2,000 ropanis of land to the temple trust for its use which today includes sacred spots such as Gorakhnath, Biswaroop, Guheswori, and Kirateswore. Green parks like the Bhandarkhal Ban, and the forest surrounding Guheswori function as Kathmandu's lungs as the city groans and grows.

The Pashupati Area Development Trust (PADT) was created in 1988 to manage the real estate belonging to Nepal's patron deity. The same year it was also included as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's tasks included not only safeguarding the area's historic flavour but also preserving its cultural and religious significance.

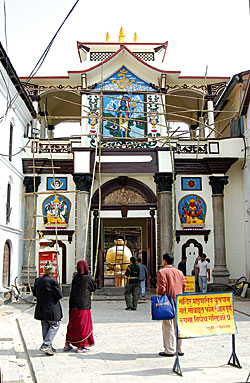

In 2000, a 10-year master plan began work shifting squatters, tearing down at least 100 illegal buildings. That angered some people. "The problem with the removal of illegal squatters was not just due to the way PADT handled it but also because of the lack of foresight with the local administration, which approved some as local residents and denied others," says freelance journalist KB Prem Vikari. However even critics now agree that the Trust has done commendable work.  PADT Chairman, industrialist Basanta Chaudhary, has been a key force in pushing the project. "We have our challenges. With temples like Pashupati, which has the sentiments of one billion Hindus worldwide attached to it, we have to balance social and religious obligations," he told us. Half the masterplan work has now been completed and the effect can already be seen in the clean wide streets and the management of the shops.

PADT Chairman, industrialist Basanta Chaudhary, has been a key force in pushing the project. "We have our challenges. With temples like Pashupati, which has the sentiments of one billion Hindus worldwide attached to it, we have to balance social and religious obligations," he told us. Half the masterplan work has now been completed and the effect can already be seen in the clean wide streets and the management of the shops.

Plastic has been banned, the Bagmati flows cleaner because of sewage control upstream. A one-stop shop for cremation rites has opened in Arya Ghat and an electric cremation is on the way. The ground outside the temple is being paved with granite and marble and a proper park is being constructed. Stone waterspouts where the faithful can wash before and after praying actually have water flowing through them.

Money was never a question. The faithful have their own ways of thanking the Lord and they go beyond making offerings to the main temple. The issue was always lack of resolve to improve the situation. There were small hiccups along the way like when devotees were prevented from performing prayers in Kirateswor Mahadeb. They built a shrine on a mound next to the temple and then constructed a shed to protect the shrine from the elements. But the PADT demolished the shed because it did not conform to architectural guidelines.

"Except for the handling of the illegal squatters and construction case the trust has done great work," says Prabin Thapa, a 23-year-old tourist guide from the area. But the PADT has one more major case to solve before it can declare the master plan a complete success-the temple's legendary treasury, the keys to which traditionally lie with Bhatta priests from South India.  There is a good reason why the main priests of the official protector deity of Nepal hail from South India. In times of national mourning, such as the recent deaths of the royal family, the rules of mourning apply to every Nepali Hindu but not to the Bhattas. According to the shastras, a priest in mourning is not pure enough to perform purification and religious rites but foreign priests can.

There is a good reason why the main priests of the official protector deity of Nepal hail from South India. In times of national mourning, such as the recent deaths of the royal family, the rules of mourning apply to every Nepali Hindu but not to the Bhattas. According to the shastras, a priest in mourning is not pure enough to perform purification and religious rites but foreign priests can.

The Bhattas get the money donated to the main temple, which according to some is less than that collected from outside the main temple, which goes to the Raj Bhandari priests. This state of affairs has erupted into controversy every now and then, in part due to nationalistic sentiments but also because the handling of the temple's money is not transparent enough. A thorough and transparent auditing of the temple's treasury is one issue that the Trust is now looking forward to solve.

Last days at the lord's doorstep

Established in 1882 as Pashupati Pakshala by King Surendra Bikram Shah, the present day Pashupati Bridashram is the country's oldest and only government-run old age home. This is where 230 elders, 140 women and 90 men, spend their final days happy that they can breathe their last in peace at the lord's doorstep. Residents need to be above 65 and have a recommendation from local officials certifying that they do not have a caretaker, are poor and in weak health. Twenty staff are employed here to look after residents' food, health and cremation, also paid by the government. This year's budget is Rs 6.8 million.

"I have an extended family. These old people are living history, the gods who speak. The one who doesn't is inside," says administrative head Arjun Prasad Gautam, whose major preoccupation today is finding the space to accommodate 230 elderly people comfortably. The PADT renovated three wings of the Bridhashram but it is not sufficient and Gautam is now pushing for a plan to construct a modern building with full facilities.