An event of huge significance happened for some of South Asia's most disadvantaged children in August. They came home. In Lahore they were met by their parents, some of whom were in tears. They had been tricked to become camel jockeys in the Gulf.

An event of huge significance happened for some of South Asia's most disadvantaged children in August. They came home. In Lahore they were met by their parents, some of whom were in tears. They had been tricked to become camel jockeys in the Gulf.

In May the UAE changed its law so that only those aged 18 or over could act as jockeys. This, we hope, will mean an end to the practice of agents preying on children from families who are desperate for them to have a better life but who are not informed of the terrible dangers they face. In a process that is still continuing the Punjab government and UNICEF are working to reunite families and make life better for the returnees, some of whom are still very young.

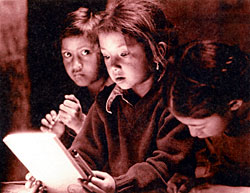

This intervention demonstrates what can be done when we all-states, families, humanitarian workers and the media-come together to turn around unacceptable practices and conditions. This week UNICEF is publishing a report that is concentrating on children who are 'excluded' and 'invisible'. Too many children are simply not being counted. Too many are not getting health care or the food they need to develop. Children who are 'invisible' are neglected and made much more vulnerable to abuse.

This is not normal and it should not be ignored. It would be difficult to imagine much of a future for nations that deny the value and potential of up to half the population. South Asia regrettably has some 24 million children who are not registered at birth, which makes it the region with the highest number of unregistered births in the world. This marginalisation plays into South Asia's immense child labour and trafficking problem, which often keeps children locked in poverty through debt bondage and exclusion from education. It is estimated that 43 million children are not enrolled at schools in South Asia and up to 60 percent of those are girls. What happens to girls in South Asia who are denied opportunities? Too often they are robbed of their childhood, with dramatic consequences.

A household survey conducted by UNICEF in 49 developing countries this year suggested that 48 percent of females in South Asia aged 15-24 had married before they were 18. Pregnancy related deaths are the leading cause of mortality for 15-19 year old adolescents worldwide. Those under 15 are five times more likely to die than women in their 20's and their children are less likely to survive.

Keeping large numbers of children excluded and invisible has a high cost. It costs them their rights, and it costs states as they lose out on the benefit of having engaged citizens who are economically thriving.

It need not be like this. South Asia's governments devoted three major points in the SAARC declaration in November to the immediate needs of women and children, and applauded the resolve demonstrated by the ratification of Conventions relating to Trafficking and the promotion of child welfare.

Children need to be included in statistics. Let us 'see' them in government analysis and planning. But in addition let us really see the impoverished, the street child and the tiny domestic worker. And when we see them, let us look them in the eye and let them know that they are not invisible to us.

Cecilia Lotse is the regional director for South Asia of the UN Children's' Fund.

Every child counts

Nepali children start suffering before they are born because of the exclusion and neglect of their mothers. They are born underweight because their mothers are anemic. Most children don't have birth registrtion. Many mothers can't take proper care of their babies because of overwork. Then, if they are girls, they suffer through their childhoods working harder and eating less than their brothers. Then they are married, often in childhood and ill-treated by husbands' families.

Nepali children start suffering before they are born because of the exclusion and neglect of their mothers. They are born underweight because their mothers are anemic. Most children don't have birth registrtion. Many mothers can't take proper care of their babies because of overwork. Then, if they are girls, they suffer through their childhoods working harder and eating less than their brothers. Then they are married, often in childhood and ill-treated by husbands' families.

And still we wonder why the male-female ratio in Nepal is so skewed. Why Nepal is still one of the few places in the world where men on average live longer than women, where the number of women who can read or write is half that of men, and our maternal mortality rate is the highest in Asia.

At the rate we are going, Nepal is unlikely to meet most of the Millennium Development Goals to eradicate extreme hunger, achieve universal primary education, have equal enrolment of girls and halve child mortality by 2015. Nepal has made progress-especially in the 15 years since the restoration of democracy. In 1990 out of 1,000 babies born alive, 145 never lived till their fifth birthday. Today, that number has been halved.

But there are still many children who are left out. They are excluded because they are poor, because they are not from the dominant ethnic groups, because they live in remote areas, because the state either doesn't care or is too inefficient. In Nepal the conflict has worsened child neglect.

Many Nepali children are also invisible because their births are never registered. They don't appear on national statistics and if they are street children, refugee children, internally displaced children, trafficked children or child workers they are exposed to further exploitation and discrimination.

UNICEF's Excluded and Invisible report has special relevance to Nepal because so many of our children are left out and not seen. Boys and girls in hazardous jobs who don't go to school or are exploited as domestics, children who are sold or trafficked. Children displaced by war, children who run away from home to live on city streets. They don't go to school, they don't have health care many are separated from parents and are exploited in conditions of near-slavery. For the state, they just don't exist.

UNICEF reminds governments of their responsibility to protect children. The report has a list of action points: mandatory birth registration, increasing allocation for social welfare, implementation of legislation on child rights, prosecution of those committing crimes against children, educating children themselves on their rights.

The report is international but on exclusion UNICEF's antidotes for Nepal are long-term and tied up with the solution of other crises as well. Including children will also mean an inclusive democracy when they grow up, it will ensure sustainable peace, decentralisation of political and economic power to the grassroots to make service delivery more effective for tomorrow's children as well.

Kunda Dixit