The innocent yet exotic, gajalu face of Nepal's living goddess, the Kumari, looking out of the wooden windows from her palace has inspired writers and photographers since time immemorial. Scott Berry is no exception: perhaps the only difference between him and many others who have written about the goddess is that Berry was fascinated by the life of an ex-Kumari.

The innocent yet exotic, gajalu face of Nepal's living goddess, the Kumari, looking out of the wooden windows from her palace has inspired writers and photographers since time immemorial. Scott Berry is no exception: perhaps the only difference between him and many others who have written about the goddess is that Berry was fascinated by the life of an ex-Kumari.

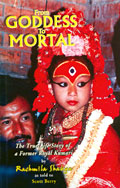

From Goddess to Mortal is the story of a former Kumari, Rashmila Shakya, who was chosen to be the living goddess at the age of four and spent eight years away from her parents at Kumari Ghar living a life vastly different from that of a conventional young girl. The book describes her struggles as she makes the transition from the world of innocence to a life of common matters. This is also a young woman's quest to correct the world's exotic misconceptions about Kumaris.

A Kumari is said to represent the Hindu goddess Durga. The first few chapters of From Goddess to Mortal chart Rashmila's life and duties as a goddess, focussing on the festivals that are significant to a Kumari. No one describes the streets of Kathmandu better than Rashmila. As the reader follows the Indra Jatra procession through the eyes of a Kumari on a palanquin, the sights, sounds and smells of Hanuman Dhoka, Thamel, Kilagal Tahity, Jyatha, Asan Tol, Jana Baha and Indra Chok flood the reader's senses.

The book's most poignant section describes Rashmila's transition from the life of a Kumari to that of a normal 12-year-old. Life after Kumari Ghar is not easy for her. When she leaves her palace she is virtually illiterate. Put in Grade Two, she works doubly hard to catch up with her classmates, and the struggle continues through her teenage years. To the most part she succeeds, but at times reality hits her with a thud.  Berry , who has lived in Nepal for several years, is the author of A Stranger in Tibet and tells the former Kumari's story in simple yet vivid language. For her part, Rashmila uses From Goddess to Mortal for a few specific purposes. She is very critical of the media, both western and Nepali, for often resorting to clich?s about the Kumari. For instance, she explains that she was never made to spend a night in a room with 108 freshly severed goat and buffalo heads to prove her courage. Nor did she have to undergo a particularly rigorous physical examination. Rashmila says she cannot claim the 32 signs of perfection that Kumaris are said to posses: "If unusually fair skin had really been one of the criteria, I wouldn't have stood a chance," she says.

Berry , who has lived in Nepal for several years, is the author of A Stranger in Tibet and tells the former Kumari's story in simple yet vivid language. For her part, Rashmila uses From Goddess to Mortal for a few specific purposes. She is very critical of the media, both western and Nepali, for often resorting to clich?s about the Kumari. For instance, she explains that she was never made to spend a night in a room with 108 freshly severed goat and buffalo heads to prove her courage. Nor did she have to undergo a particularly rigorous physical examination. Rashmila says she cannot claim the 32 signs of perfection that Kumaris are said to posses: "If unusually fair skin had really been one of the criteria, I wouldn't have stood a chance," she says.

Not only a critic, she also points out that life for present and former Kumaris is improving-a goddess now has a chance at being educated while she is serving. But many institutional changes are still needed and Rashmila makes some suggestions: serving Kumaris need to be treated a little less like goddesses and more like normal young girls, while a scholarship to finance higher studies would cost the government much less than a pension for life. If such changes were to be put into place, Rashmila says she would have no qualms about advising other young girls to serve as a Kumari

From Goddess to Mortal proves that a lot of the more spectacular stories we hear about Kumaris are wrong. The book succeeds in calling attention to reporters who are keen on writing stories about exotic lands without doing formal research and is a good example of how, with repetition, writers' misconceptions become accepted as the truth over the years.

It is also very clear from Rashmila's story that it is possible and not exceedingly difficult for a former Kumari to readjust to society, particularly with a little help from her family.