Are we seeing the last days of the Nepali readymade garment industry that employs 60,000 people? Yes and no.

Are we seeing the last days of the Nepali readymade garment industry that employs 60,000 people? Yes and no. The story of garments in Nepal has long been not of entrepreneurship and business savvy but of luck and charity. Sadly, both are about to run out on 1 January when quotas are lifted, forcing Nepal to compete for markets and customers with the whole world. Meantime, according to a report published by the Garment Association of Nepal (GAN), Nepal's annual exports to the US (worth a little over $100 million), which accounts for 80 percent of our garment exports have been declining all of this year.

On the other hand, if Nepal accepts the changing global reality, looks around the region, understands what China, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are doing, then figures out what it can do to carve out a niche for itself, it can remain a player. Such a repositioning would mean weak players would be forced out of the market but the stronger ones can consolidate their operations, focus only on doing things they do very well and transform the way they conduct business to remain competitive.

So far, except for Surya Nepal (whose markets are growing in India, thanks in part to the corporate muscle of its parent ITC) the media reports in Nepal have been coloured by panic, gloom and a cry for help and not by the evidence of quiet and careful strategising.

A readymade garment company is a low-tech but labour-intensive venture. Historically, countries with low labour costs on the cusp of industrialisation have used it to give themselves a jumpstart to earn foreign currency. As those countries did well economically, they started seeing their labour costs rise. They then moved up the value chain to design, market, distribute and sell the garments while farming out bulk production to countries with lower labour costs.

For many years, this was a template for an arrangement between rich and poor countries, whereby the former would offer market-access benefits and provide guaranteed secure markets for the products. Since the late 1980s, Indian businessmen came to set up shops with local investors and Nepal has benefited. Indeed, before international buyers started slapping social and environmental compliance codes on their Nepal-based suppliers, there was a time when every fourth house in New Baneswor was a tubelight-powered garment sweatshop. Garment exporters made money like there was no tomorrow.

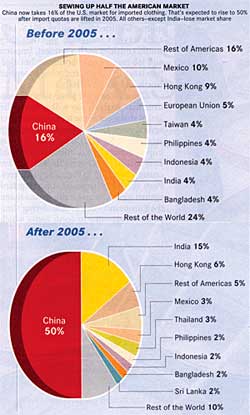

The curtains on sheltered markets are about to be lifted, these businessmen will find their products under the glare of harsh global competition. Unfortunately for them, competition is dictated entirely by the actions of companies such as Wal-Mart, GAP, JC Penney, H&M and others, who can now dump Nepal in favour of countries with stronger relationships with buying houses, lower labour costs, or lower political risks, or better technological base for converting fibre to fabrics or lower costs of doing business and higher overall reliability (Translation? The elephants next door known as China and India, not to mention tiny Bangladesh with an RMG industry with annual exports worth $5 billion).

Instead of continuing to knock on US Senator Diane Feinstein's (D-CA) door for additional time-bound protections that are unlikely to happen, the choices before the Nepali readymade garment industry are twofold: either find a niche in the regional and global markets or perish altogether.