Every morning as the sun illuminates the fluted ridges of Ama Dablam, 80-year-old Dorje Sherpa sits quietly in front of his house in Dingboche and stares up at the mountain.

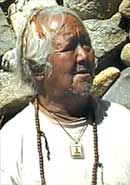

Every morning as the sun illuminates the fluted ridges of Ama Dablam, 80-year-old Dorje Sherpa sits quietly in front of his house in Dingboche and stares up at the mountain. His eyes are moist as he recalls how his young daughter and grandchild were killed 12 years ago in a flashflood. The glacial lake below Ama Dablam burst and a wall of ice blocks, boulders and water crushed his daughter's house. Dorje and his wife were sleeping in the monastery when they were awakened by the guttural thunder of the avalanche. They ran out, and watched helplessly as the boulders smashed into the small house where their daughter and grandchild slept. "The gods must have been angry, why else would it have happened?" says Dorje, as his wife motions him to stop talking.

Like mountain people elsewhere, Dorje and other villagers here have never heard of global warming, which is causing the snow to melt, the glacial lakes to swell up and triggering avalanches and floods. Up here, the Sherpas blame themselves for paying less attention to dharma. Older Sherpas, including learned monks, are from the spiritual school and don't see the rational explanation to the changes that are transforming the Himalaya in their lifetime. In 1985, the Dig Tsho glacial lake near Thame burst and the flood rushed 90km down the Dudh Kosi, killing 12 people and destroying bridges, trails and Namche Bajar's $1.5 million hydropower plant. There were rumours that someone killed an animal and threw it into the lake, and the angry gods punished the people with the flood.

"We try to explain to them that it is all because industrialised nations are burning fossil fuels," says Sandip C Rai, a climate change expert with the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF). "But it is hard to explain why." Scientists say GLOFs (glacial lake outburst flood) are caused when increased snow melt causes the glacial lakes to overflow or burst.

"We try to explain to them that it is all because industrialised nations are burning fossil fuels," says Sandip C Rai, a climate change expert with the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF). "But it is hard to explain why." Scientists say GLOFs (glacial lake outburst flood) are caused when increased snow melt causes the glacial lakes to overflow or burst. "We were lucky that the flood occurred during the daytime. A lot of people could have died if this had happened at night," explains 32-year-old Ang Maya Sherpa, who was just a teenager then. Ang Maya, who took us on the eight-hour walk up to the lake, relates how the yaks tried to escape to higher ground but were swept away by the brown wall of water and ice. Nearly 20 years later, the scars of that terrible flood can still be seen on the banks of the river.

"Only humans survived that day, but lost everything," explains 85-year-old Lama Dorje in Ghat. He lost two houses, a huge tract of land and several cattle due to the flood. "All my houses and wealth is under that debris," says Lama Dorje, pointing to the gorge that formed when half the village was torn apart.

"Only humans survived that day, but lost everything," explains 85-year-old Lama Dorje in Ghat. He lost two houses, a huge tract of land and several cattle due to the flood. "All my houses and wealth is under that debris," says Lama Dorje, pointing to the gorge that formed when half the village was torn apart. There are fears that Imja Lake (see pic, top), across the valley, could also burst in the next five years. A team of Japanese researchers studying the lake have assured villagers that there is no immediate danger. "The younger generation is actually more scared because they know about global warming," says 21-year-old Tenzing K Sherpa, son of one of the five Sherpas who portered for the Hillary expedition in 1953.

Tenzing was 12 when he started working as a mountain guide, travelling frequently to Everest, Ama Dablam, Nuptse and Lhotse base camps. "My generation now understands that these things are not the Nepali people's fault, but because of excessive fossil fuel burning that is warming the atmosphere."

Imja Glacier is receding at an astounding 10m a year as average temperatures rise. The lake, which was first observed in 1960, is currently 100m deep, 500m wide and 2km long and holds 28 million cubic metres of water dammed behind an unstable moraine wall. If the wall breaks, the entire Dingboche valley will be swept away. "Just imagine what would happen. We shouldn't wait for it, we should do something now," says 13-year-old Soni Sherpa from Khumjung School, who is here on an educational tour with her class and geography teacher.

Imja Glacier is receding at an astounding 10m a year as average temperatures rise. The lake, which was first observed in 1960, is currently 100m deep, 500m wide and 2km long and holds 28 million cubic metres of water dammed behind an unstable moraine wall. If the wall breaks, the entire Dingboche valley will be swept away. "Just imagine what would happen. We shouldn't wait for it, we should do something now," says 13-year-old Soni Sherpa from Khumjung School, who is here on an educational tour with her class and geography teacher.