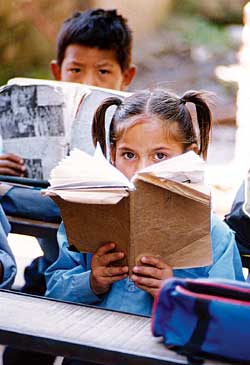

For the first time in Nepal's history, the government is mulling over a job quota for women and marginalised communities in the civil service.

For the first time in Nepal's history, the government is mulling over a job quota for women and marginalised communities in the civil service. Dalits, madhesis, other ethnic groups and women will benefit from the scheme which is expected to be implemented by April along the lines recommended by the Reservation Provision-related Advisory Committee led by Finance Minister Prakash Chandra Lohani. The five-member task force has less than 45 days to complete its work.

The reason for the government's rush to take the initiative on affirmative action appears to be aimed at countering the Maoist moves towards local autonomy and to defuse its demand for inclusion of ethnic communities in the national mainstream.

During last year's peace process, the government conceded to the Maoist demand to establish a reservation policy which included proposals for a five-year quota system in the civil service: 20 percent for women, 10 percent for dalits and five percent for indigenous communities. Following protests, the government formed a committee to come up with new recommendations. Time is running out and many wonder if the job can be finished on time.

"This is a landmark for the government," says Dambar Narayan Yadav, member of Nepal Sadbhabana Party and coordinator of a sub-committee for reservation for madhesi people. "The tarai population has been politically debarred from equal participation and left out of economic and development processes."

The sub-committee looking at quotas for women is recommending proportional representation based on the national census. Women have only eight percent of civil service jobs, only two percent of judges are female. "There are 525 females working in government jobs and most are still not considered permanent staff even after working there for decades," says Durga Pokhrel of the National Women Commission. Pokhrel says there should be at least one seat for a female joint-secretary in each ministry. "It's time to act now and this is the right way. Just talking about women's problems will not result in action," she told us.

Figuring out a quota system for madhesi, janjati and dalit communities may be easier said than done. There are over 100 ethnic and caste groups in the country and there is no agreement about which are eligible for reservation. Many fear quota percentages might be excessive in some cases and end up leaving others out altogether.

While the reservation policy sounds good in theory, many are sceptical about whether it will work in practice in reducing social exclusion. There are also questions on why the government is in such a rush to implement the policy by April.

"There is immense pressure from donor agencies," a janjati activist, who has reservations about reservation, told us. Nepal's donors are convinced the root of the country's inequities stem from social exclusion and are pushing for a proactive government approach to redress the imbalance. They have even threatened to pull out funding if the policy is not implemented soon.

"The Netherlands has already taken a strong stand," a government source, confirming the pressure, told us. The UNDP is hiring international consultants to develop its own plans for reservation in case the government committee fails to deliver. This has angered officials, who say the UN is wasting money. "There is no need for the UNDP to duplicate the work of the government and spend so much on international consultants," said one official, who requested anonymity.

"The Netherlands has already taken a strong stand," a government source, confirming the pressure, told us. The UNDP is hiring international consultants to develop its own plans for reservation in case the government committee fails to deliver. This has angered officials, who say the UN is wasting money. "There is no need for the UNDP to duplicate the work of the government and spend so much on international consultants," said one official, who requested anonymity. Several janjati activists are asking the government not to jump into the reservation bandwagon without studying the implications just because of donor pressure. They say the policy may fail to achieve its goal of proportionate representation for all communities in the civil service, and may even result in greater disparities and discord. "This policy might never be implemented," says anthropologist and researcher, Mukta Lama. "There are no associated laws or a systematic approach needed to make it successful."

The haste with which the Maoists started declaring ethnic-based autonomous regions, most recently Magarant and Tharuwan, appears to be an effort to stay one step ahead of the government. This may explain the government's tearing hurry to get the job finished.

Some independent researchers admit affirmative action elsewhere in the world has met with mixed results but do not doubt that a well-planned quota policy is necessary because of Nepal's entrenched exclusion. Says Bal Gopal Baidya, former member of the National Planning Commission: "Obviously, this is a controversial issue, but affirmation action is needed. Things will not change on their own."

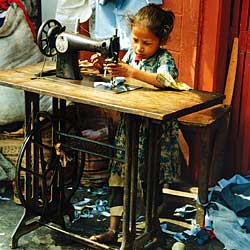

Bahuns, Chettris and Newars together make up 37 percent of the population but dominate 82 percent of politics, bureaucracy and education. Twenty percent of Nepalis are dalits, but there hasn't been a single dalit minister since 1990.

Surprisingly, it is dalit and janjati activists who are not convinced about reservation. "The main problem is a centralised and unitary governance system, so what is more urgent is devolution to a federal democratic structure by establishing ethno-linguistic autonomous regions without compromising the unity of our nation," says activist

and academician Bal Krishna Mahubang.

Buddhiman Tamang, adviser to the National Federation of Indigenous Communities, agrees: "What the government is doing is quite revolutionary and we really appreciate it, but this is something an elected government should be doing. Right now, this might just be a political gimmick."

Activists doubt that the government's small task force on reservation can do justice to such an enormous problem. Why not start with local self-governance, they say, that will lead automatically to greater representation of minorities and help pull the rug from under the Maoists.