The biggest problem with Nepal benefiting from information technology is affordability and accessibility. Computers, internet fees, or telephone fees are too expensive and convergence applications need the English language. No one has done an accurate study, but it is estimated about one million Nepalis read or speak English. That is roughly five percent of the population. This keeps 95 percent of Nepal's 24 million people away from computers, solely because they don't know its primary language of use.

The biggest problem with Nepal benefiting from information technology is affordability and accessibility. Computers, internet fees, or telephone fees are too expensive and convergence applications need the English language. No one has done an accurate study, but it is estimated about one million Nepalis read or speak English. That is roughly five percent of the population. This keeps 95 percent of Nepal's 24 million people away from computers, solely because they don't know its primary language of use. There's more: Nepal's literacy rate is estimated at 42 percent. This means that even if the computer with all its applications was available in Nepali, more than half would not be able to use it. This is where those involved in computer literacy and applications in Nepal must get out of their ke garne attitude and make computers at least accessible to literate Nepalis to start with. There is no point saying, oh well, Nepalis will never be able to afford computers and it is only for the rich countries. With that kind of fatalistic attitude we will just be left further and further behind. If only we broaden our horizon and see the real possibilities with information and communications technologies, computers will not only be relevant but may even allow us to leapfrog in education, governance and commerce.

So far, we in Nepal have defined literacy along very narrow terms: reading and writing. Leaving aside the fact that what we read may not be relevant to our daily needs, and there may be no reason to write, it leaves half the population out of the loop. Can technology address the needs of that segment of the population? Reading is only a medium through which one learns new things. If the text books are old-fashioned, and carry wrong or inappropriate values, then literacy (as is conceived in Nepal) can actually be a liability to the nation. Can we still learn without having to learn reading or writing? What are the possibilities?

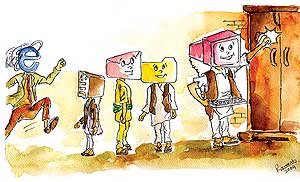

Contrary to popular views, it is not the 'technical expertise' that's stopping people from learning and using computers. Learning how to drive requires a lot of coordination between hand, eyes and feet. Yet, thousands of Nepalis have mastered driving. Not all of them drive responsibly, it must be said, but that technology did not faze them. Then why should computer technology? People learn best when they find a technology and find out about its real usage. Maybe more Nepalis aren't into computers because they can not think of enough good reasons to use them. So how about letting people know the benefits of computers first in the way they understand it: by showing practical benefits of using the computers for various purposes in their lives.

As often is the case, we (the technocrats) tend to decide how the people will benefit from ICT without even considering-or asking-what their real needs are. Rather than emotionalising the issues, we have to be clear that not everybody would benefit from ICT. The option would be to provide accessibility to those who can benefit from it. Accessibility here means a lot of things. It means providing the content and interface of the technology in the local language for those who are literate in the local language. It also means providing multi-modal approaches to those who are illiterate. Speech recognition in the local language would surely make ICT accessible to those illiterate. Similarly visual interface with touch-screen facility would go beyond the language barrier.

Professor Kenneth Keniston said at a recent meeting in Kathmandu: "The role of language and localization vis-?-vis the digital divide, while not denying the technological component, is primarily a matter of cultural and ultimately political significance." It is the desire and commitment to providing accessibility of ICT to the people that is important. People are not stupid. Once they have the access, they will decide for themselves the ways of using ICT and harnessing benefits from it. So let's seriously start about taking technology to the people rather than the other way round.