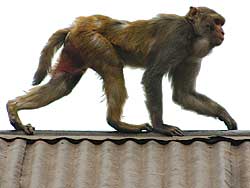

They're our closest neighbours in the chain of species. Which is exactly why Rhesus monkeys are so highly valued in bio-medical research. Except now there is a global shortage of primates because many countries have imposed bans on their export. Here in Nepal, monkeys share our streets, neighbourhoods and temples-and we're not party to any bans. Little wonder then, that the world's largest primate importers are wooing us.

They're our closest neighbours in the chain of species. Which is exactly why Rhesus monkeys are so highly valued in bio-medical research. Except now there is a global shortage of primates because many countries have imposed bans on their export. Here in Nepal, monkeys share our streets, neighbourhoods and temples-and we're not party to any bans. Little wonder then, that the world's largest primate importers are wooing us. Plans are already underway to set up a primate facility in the country funded by the US federal government. The Division of International Programs of the Washington National Primate Research Center (WoNPRC), established in 1999, supports two long-standing international programs in Indonesia and Russia. The third one was reportedly established in Nepal in collaboration with Natural History of Society of Nepal (NAHSON). Randall Kyes, head of International Programs at the Washington National Primate Research Centre, has already visited Nepal several times to establish a primate program.

The Nepali face aligned to the American drive is monkey specialist Mukesh Chalise. In 2001, he approached the King Mahendra Trust for Nature Conservation (KMTNC) to start a primate research centre and a clinical research laboratory in microbiology in Nepal. His proposal received a strongly worded response from the trustees: "The objectives of the centre can be called a combined wishlist of zoo keepers, epidemiologists, veterinarians, microbiologists, primatologists and biomedical researchers using non-human primates. The proposal is faulty.(and) ambitiously yields to the international experts and their funds which it says will bring sustainability. It is wrong."

Three years later, Chalise could be luckier. The Wildlife Farming Act passed last year by the government allows anyone to rear and breed certain wildlife. "He has to present a detailed work plan and then only will we decide to what extent the government will support him," says ecologist Shyam Bajimaya from the Department of National Parks & Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC). They are waiting to receive his proposal to start a breeding and research centre.

Conservationists are suspicious about the extent of the government's support of Chalise. They are worried that he may be allowed to export rhesus monkeys abroad to research laboratories where scientists are willing to pay $5,000 - 10,000 for each monkey. The DNPWC has already agreed to supply the monkeys from the national parks to Chalise for breeding purposes at Rs 25,000 per monkey. He can begin business with the second generation. "If there is surplus population, there is no obstacle for him to export them," adds Bajimaya.

While this may be a simple issue for the government, animal rights activists and conservationists are worried about the cruelty involved in scientific research in US laboratories. Some are asking for a national debate on the issue before the government legalises export of any animals for research. Noted biologist Pralad Yonzon is frustrated with the silence of conservationists working in dozens of international conservation organisations in Nepal. "If the conservationists are not raising the issue then that is a huge problem. We should never allow Nepal's monkeys to be used for bio medical research," says Yonzon who also runs Resource Himalaya, a private independent regional biodiversity organisation.

Until a few years ago, the Philippines and Indonesia used to be two of the biggest exporters to the United States. But both countries have now made the export of monkeys illegal. One of the first countries to impose the ban was India in 1977, after pressure from the International Primate Protection League (IPPL), begun by Shirley McGreal in 1973. McGreal influenced the Indian ban by publicising gruesome radiation experiments on monkeys, which are sacred to many Hindus. There was a time when India exported more than 100,000 monkeys a year during the 1950s.

Indonesia introduced the ban nearly two years after 110 monkeys died en route from Inquatex, a Jakarta supplier, to Worldwide Primates. This was followed by the Philippines, Bangladesh and Malaysia. But this crucial step had not been easy with US pressure mounting on these countries. McGreal says that the State Department threatened to cut off foreign aid unless Bangladesh renewed monkey exports immediately. "The US government and even the World Health Organisation exerted pressure on India to reopen exports," said McGreal.

Nepal-based animal welfare activist Lucia de Vries says: "The US, keen to conduct bioterrorism experiments on primates, is desperate for lab monkeys, which is why they turn to countries with weak legislation and a willingness to sacrifice its precious wildlife, such as China, Vietnam, Indonesia and, lately, Nepal." While exporting monkeys from Nepal has not begun and may take a while, this is exactly why many believe it is the right time for the government to tackle this issue seriously. "There needs to be a debate before the government takes another big step by letting the monkeys be exported," says noted naturalist Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha.

Primates continue to be essential to medical research, especially to study AIDS. Scientists say that monkeys make major contributions to the study of cancer, dental research and malaria treatment as well. According to the US Department of Agriculture, more than 49,000 monkeys and apes were used in medical research in 2001. "If this is about cruelty, then we should stop slaughtering animals and killing vegetables for food too," says Chalise. "Common species should be used for human welfare. There is no harm in exporting monkeys."