Located just outside the Valley rim, the villages to the south of Lele show the effects of eight years of Maoist insurgency: settlements devoid of young men, fallow terraces, deserted bazars.

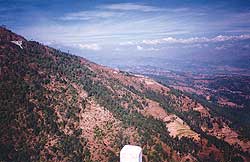

Located just outside the Valley rim, the villages to the south of Lele show the effects of eight years of Maoist insurgency: settlements devoid of young men, fallow terraces, deserted bazars. But there is another unintended side effect: a dramatic rejuvenation of the once denuded mountains surrounding this rugged and picturesque region on the outskirts of Kathmandu. The conflict and violence has depopulated Nepal's midhills, reducing pressure on the land, and villagers are afraid of going into the forest for fear of running into Maoists. The two factors combined have given the forests a chance to grow back.

"We don't enter the forest much these days to cut fodder leaves or to graze goats and cattle, that is why the trees are so thick," says Sumitra Godar, who is a forest guard with the all-women Sallaghari Community Forest User Group in the village of Mahat. "There are now a lot more birds and wildlife."

There has been some fighting in the mountains to the south and east of Lele, and the frequent checks along the highways have restricted the mobility of the villagers. This too has helped forest regeneration, and because of the trees the women say they have noticed many more birds and wild animals such as leopards, bears and pheasants. Regeneration has been so rapid that leopards and other wild animals have actually become the number one concern of many farmers who have suffered increasing livestock losses.

"Forest stock has visibly increased in recent years in southern Lalitpur, and this scenario is replicated in other parts of the midhills as well," says Ram Balak Yadav at the district forest office in Hatiban.

To be sure, not all effects of the insurgency on the environment have been so benign. The deployment of the Royal Nepali Army for counter-insurgency duty has reduced its presence guarding the national parks and nature reserves, leading to a rise in timber and wildlife poaching in Chitwan, Bardia and Dhorpatan.

Elsewhere, Maoists have deliberately targeted ranger posts and forestry officials, giving them a free hand in cutting trees for timber. In the absence of officials, large parts of remaining non-protected char kose jhhari along the tarai have been destroyed in recent years by timber smugglers. Depopulation from the hills has increased pressure on forests in the tarai.

Along Nepal's northern border with Tibet, forest destruction has reached crisis proportions in Larke Bhanjyang, parts of Mugu and eastern Nepal. Nepali logs are taken across the border to a roadhead in China by destitute villagers to barter for food. The lack of customs posts and a security presence has increased this illicit trade.

Along Nepal's northern border with Tibet, forest destruction has reached crisis proportions in Larke Bhanjyang, parts of Mugu and eastern Nepal. Nepali logs are taken across the border to a roadhead in China by destitute villagers to barter for food. The lack of customs posts and a security presence has increased this illicit trade. In other parts of Nepal, the Maoists have shown a conservation streak by hunting down timber poachers or regulating forest use. "To some extent the security situation has helped to check timber smuggling, deforestation and wildlife poaching, it has not only been because of the success of the community forestry program," says Dinesh Poudel, forest coordinator with the Nepal-Swiss Community Forestry Project.

They have stepped into the vacuum to take over forest user groups who have no members left, or community forestry projects that were abandoned. In Dolpa, for instance, the Maoists have regulated the yarchagumba and panchaule trade by slapping a fixed tax on the rare medicinal plants.

But it is in the midhills that there is a visible proof of a resurgence of forest cover. Ten years ago, the slope from Lamatar to Lakure Bhanjyang on the Valley's eastern rim used to be bare. The community forestry program started the process of regeneration, but in the past few years it has been security fears that have protected the forests. "Our forest used to be poached by other VDCs, but now everyone is afraid of going into the forest, especially on the higher ridges, and the trees have come back," says a member of the Kafle Community Forest User Group in Lamatar.

Yadav at the Hatiban forest office agrees that formerly denuded hillsides in eastern Lalitpur district are now green. "The forest cover has improved due to the community forestry program as well as the presence of the rebels higher up the mountains," he adds.

Kabhre and Sindhupalchok, east of Kathmandu, were pioneers in community forestry and they have shown what local communities can do to protect the commons. The rejuvenation of forests in these two districts can be seen even in recent satellite pictures, comparing them to Landsat images from 20 years ago.

Kabhre and Sindhupalchok, east of Kathmandu, were pioneers in community forestry and they have shown what local communities can do to protect the commons. The rejuvenation of forests in these two districts can be seen even in recent satellite pictures, comparing them to Landsat images from 20 years ago. At the all-women Koilidevi Community Forestry User Group in Budakhane in Kabhre, there has been an increasing awareness of the need to manage protected forests. In fact, forestry officials in Kabhre told us some of the community forests are "over-protected", and need to be managed. For example, forests have 1,400 trees per hectares, whereas a healthy density is less than half that. In addition, there has been a 13 percent increase in forest area in the past five years after the insurgency intensified in these two districts.

The user groups are now learning how to manage their pine forests by culling commercially-viable trees without disturbing the forest. "This way, we keep the forest healthy, while the community earns money to invest in schools, health posts and roads," said a woman from the Koilidevi Coummnity Forest User Group. In fact, community groups in Chaubas and Srichhap Deurali have set up saw mills to add value to their forest products. Since the mills came up, other VDCs in the area are also setting up commercial forests.

The security situation has also helped protect the forests where lokta and chirayito plants used to be unsustainably gathered to supply the demand of the traditional Nepali paper industry. "Today, the forests are completely protected because the areas with the best growth are strongholds of the Maoists," says Suman Dhoj Kunwar of the Federation of Community Forest User Groups in Kabhre.

Other forestry officials caution that it isn't a uniform scenario throughout the country, but the security situation does seem to have dispirited poachers and smugglers. Even in the inner-tarai and tarai, where there has traditionally been much more rapid deforestation in the past 30 years, the insurgency appears to be slowing the trend. Saptari and Rautahat in the east have seen more deforestation, timber smuggling and wildlife poaching. But in other parts of the plains, the security situation has actually protected the trees. There are frequent reports of the security forces shooting wildlife poachers dead in the buffer zones of national parks, and even Maoists apprehending timber smugglers heading towards the border.