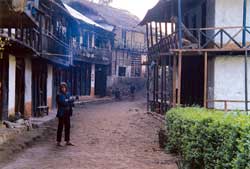

This is a part of Nepal where, in the old days, you knew you were approaching a village when children on a ridge would sing or yell "Namaste" to any passing stranger. Nowadays, all you get are silent, suspicious stares.

This is a part of Nepal where, in the old days, you knew you were approaching a village when children on a ridge would sing or yell "Namaste" to any passing stranger. Nowadays, all you get are silent, suspicious stares. Like many Nepalis caught up in this pointless war, Pasang Bhutia, the 55-year-old former chairman of Yamphudin VDC just wanted to be left alone by both sides. He lived with his wife, and his four daughters and one son went to school in Taplejung. Pasang allegedly used to be a Maoist sympathiser, but wasn't anymore.

On the night of 8 November, a group of 10 armed Maoists came to his house seeking shelter. Pasang and his wife couldn't say no. In the morning, word reached the village that an army patrol was approaching. The Maoists ran off, leaving their weapons behind. The soldiers went house-to-house and when they saw the weapons, they opened fire killing Pasang on the spot. His wife waited all day and the following night beside her husband's dead body, unable to do anything but grieve.

The next day, the villagers finally mustered the courage to help her carry out the last rites. That evening, they heard Radio Nepal announce that a Maoist, Pasang Bhutia, had been shot dead by security forces in Taplejung. Pasang has become another statistic. But for his family, his community and his country, he is yet another Nepali who was caught in this vicious and senseless conflict.

Three years ago, Taplejung was untouched by the insurgency and had a bright future ahead. The infusion of remittances from soldiers and workers abroad was making a visible difference to living standards, and local elected officials had started improving health and education.

Farmers were farming cardamom, and the cash crop was bringing in up to Rs 450 per kg. The Kanchenjunga Conservation Area Project (KCAP) initiated by the World Wide Fund was promoting ecotourism as a way to raise living standards and conserve the region's biodiversity around the world's third highest mountain.

It was just when the future was getting rosy that the Maoists arrived with their alternative vision of a free, classless society. The Rai, Limbu, Sherpa and Gurung villagers were far too busy making a living in this rugged land to understand. First, the Maoists started taxing cardamom farmers, and took away 5kg of every 100kg harvested as 'donation'. A few farmers were threatened and punished for their reluctance to pay this new tax.

It was just when the future was getting rosy that the Maoists arrived with their alternative vision of a free, classless society. The Rai, Limbu, Sherpa and Gurung villagers were far too busy making a living in this rugged land to understand. First, the Maoists started taxing cardamom farmers, and took away 5kg of every 100kg harvested as 'donation'. A few farmers were threatened and punished for their reluctance to pay this new tax. As Maoist activity spread and after the ceasefire broke down in August, things worsened. The Maoists are active outside the district headquarters, and people like Pasang pay with their lives. Navin used to own a shop in his village of Sanwa. Three years ago the police came looking for him. When they didn't find him, Navin tells us, they beat up his wife so badly she nearly died. "I had no other choice," Navin tells us simply. "I joined." Several villagers standing around nod their heads as they listen. This is just one of many stories of brutality perpetrated by security personnel in these remote mountains.

Later, in the privacy of their homes, people in these remote villages speak in hushed tones of the 'Junglis', the name they use for the Maoists who descend into the village in the cover of darkness and force subsistence farmers to give them food and shelter. The Maoist leadership, wherever they are, may give directives to its cadre, but up here in the northeastern corner of Nepal there are other rules.

When 79-year-old Prabahang Kedem of Thinglabu refused to give Maoists the 'donations' they asked for, they tortured the old man and slit his throat. His nephew was forced to watch the execution. A week later, the party leadership denied involvement in Kedem's execution. Many villagers can't imagine who else could have carried out such a brutal act.

The Maoists officially claim to raise only minimal donations from trekkers and insist it is totally voluntary. Even though receipts are given, tourists on the Kanchenjunga trail told us extortion is arbitrary. In Yamphudin a group of 14 British trekkers were looted of everything including clothes, tents and money. They were helped back to Taplejung headquarters by locals. The incident here was so serious that it warranted a statement from Maoist spokesman Krishna Bahadur Mahara denying party involvement and promising an investigation.

As it is, the Kanchenjunga region which gets fewer trekkers than other regions, was just beginning to reap the benefits of being declared a "Gift to the Earth" by the government under WWF's Living Planet campaign. But incidents like these will affect next spring's tourist season unless there is a dramatic improvement in security. Senior KCAP staff have been unable to go to the field. Villagers along the trail who were hoping that the income from trekkers would see them through the bad times are getting desperate.

As it is, the Kanchenjunga region which gets fewer trekkers than other regions, was just beginning to reap the benefits of being declared a "Gift to the Earth" by the government under WWF's Living Planet campaign. But incidents like these will affect next spring's tourist season unless there is a dramatic improvement in security. Senior KCAP staff have been unable to go to the field. Villagers along the trail who were hoping that the income from trekkers would see them through the bad times are getting desperate. They have a saying in these parts that when two bulls fight it is the calf that gets trampled. The Maoists come by night and force villagers to provide food and shelter and the security forces come by day and punish anyone who help the Maoists. Most villagers have learnt to live with the Maoists. They are willing to give food and shelter in exchange for what little measure of peace they can get. But they are always scared when the soldiers come because then they find themselves trapped in the middle.

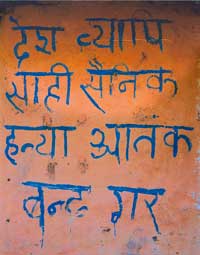

Locals told us the soldiers suspect everyone of being a Maoist and beat them up if information is not given. "When we know the army is heading our way, we know we're in trouble," one resident of Hellok village told us. "The Maoists came here when we were away during Dasai and wrote a few slogans on the school walls and raised their flag in the village, but they have not threatened us," says the headmaster of Saraswoti High School in Lelep.

From what villagers tell us, it looks like indiscriminate harassment of locals could drive them to the Maoist fold. One villager talks of how the soldiers came and emptied the granary of an entire village, another woman's sewing machine was broken and a group of KCAP staff nearly got shot at by jittery soldiers on patrol.

But this does not mean the people are willingly joining the Maoists. There is a deep-seated resentment of their methods, and despite efforts by the cadres to set up their local peoples' government, there has been little success. "So far, we have given them one excuse or another, but I don't know how long this can go on," says one village elder, who did not want to be identified for fear of reprisal.

But this does not mean the people are willingly joining the Maoists. There is a deep-seated resentment of their methods, and despite efforts by the cadres to set up their local peoples' government, there has been little success. "So far, we have given them one excuse or another, but I don't know how long this can go on," says one village elder, who did not want to be identified for fear of reprisal. Lelep's population consists mostly of Sherpas and the Maoists have tried hard to gain their confidence. But the activities of their own militia has weakened the political work. They have tried to make up by maintaining trails, repairing bridges, banning alcohol (except the warm millet drink, tongba), and petty thieves and criminals are severely punished. In Tapethok a thief who stole from offerings meant for Pathibhara Debi, Taplejung's protector deity, was publicly punished. But this is still not enough.

Rebel recruits are either those who have suffered from atrocities at the hand of the security forces or teenagers brainwashed by the glamour of a gun. "We don't force them to join us," says a Maoist in Chiruwa who calls himself Sandip. "We give them lessons on politics and tell them about the feudal system we have lived under for the last 250 years. It's up to them to join or not." Some cadre in Sandip's group don't look older than 13. Most don't know what 'feudalism' means when we talked to them. We ask Sandip about the future of these underage recruits. "The party will take care of them," he says without hesitation.

In villages people listen to the weekly army program on Radio Nepal that usually features interviews with Maoist defectors and how the army is helping locals. Most villagers we met found it hard to believe that this is the same army they see on the trails. "Who are they trying to fool?" asks a villager finishing his dinner at 7PM by the dying embers of a fire. He is used to going sleeping early, there is no telling who might turn up at the door if a light is still on.

Taplejung is settling down for another winter. It's too cold for the Maoists and they are coming down from villages up higher. The police post at Olangchunggola was burnt down two years ago, and the old customs post is abandoned. The border is only a day away and trade goes on. A kilogram of rice brought from Taplejung costs Rs 290 here, while rice from Tibet costs Rs 90. The irony is the latter is actually from Hetauda and was exported to Tibet via Khasa.

There is one bright spot in the horizon: a hydropower plant brought here nearly a decade ago has finally started working. Only a few houses in Olangchunggola have electricity because the army doesn't allow electric wire to be brought here. As darkness falls, the people lock their doors and hope the Maoists won't come calling. Day will bring little relief.