You couldn't invest in a simpler, more natural technology. Dung goes in, gas comes out. You don't need to put anything else in: even the bacteria that break down the droppings are already present in the cow's stomach.

You couldn't invest in a simpler, more natural technology. Dung goes in, gas comes out. You don't need to put anything else in: even the bacteria that break down the droppings are already present in the cow's stomach.

"It's a great investment," says Kamal Prasad Gautam from Kabhre. He built a biogas plant three months ago, and had to pay just Rs 14,000 because more than half the costs were subsidised.

"Here I put in the dung of my two buffaloes and some water," Kamal Prasad shows us, turning the stirrer over the inlet. He walks to the other side of the plant. "And here slurry comes out. I'll use it after the monsoon to manure my land. It is very fertile."

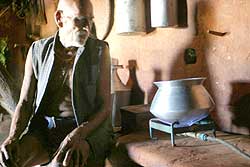

Between the inlet and the outlet, a metal pipe sticks out of the ground and runs to the kitchen. Kamal Prasad's wife, Radha, shows us how it works, turning the valve and striking a match to the cooking stove. A clear blue flame lights up the dark room. "We have enough gas for five hours of cooking every day," Radha says. "I cook rice, vegetables, milk and food for the animals. We even have gas left for tea. It's nice. I don't have to sit in the smoke anymore."

In a country where indoor pollution from smoky fires is a major cause of acute respiratory infections among children and women, biogas does not just conserve firewood, it is also a major leap forward in public health.

Gautam sums up some more advantages of his purchase. "Previously, it took us at least two hours per day to collect firewood," he says. "Now we use that time to do other work, or we just relax. Also, we no longer have to go into the field to go to the toilet." The DDC sponsored the construction of a toilet, which is connected to the biogas plant, which now runs on a combination of effluent from the goth and the toilet. The bonus is the spent slurry which is an odourless and potent fertiliser.

The first experiments with biogas in Nepal took place in the 1950s, using the Indian drum design. But the rusty drums needed expensive maintenance and the above-ground design was also unsuitable for Nepal's colder climate. In 1979, Nepali scientists modified the Chinese underground design with an air-tight dome and produced a cheap and easy-to-make prototype that worked beautifully. There are virtually no moving parts, and the underground digester keeps the slurry insulated from the cold.

Nepal's biogas campaign really took off after 1992, when the Biogas Support Program (BSP) began to subsidise farmers who had to take out a soft loan to finance the construction of the plants. The amount of subsidy depends on the remoteness of the area and the size of the plant. It is about Rs 6,000 in the tarai, Rs 9,000 in the hills and Rs 11,000 in the remote hills.

"We also select and train construction companies," says Roop Singh Thapa, a BSP quality management officer. "We carry out random checks of the work they do. If a company fails to meet the standards, it is banned from the program." In 1992, there was only one biogas company. At present, there are more than 40 private companies involved, with branches in 65 districts.

Of the 20,000 plants that have been tested, 98 percent are functioning well. "In comparison to other countries, the success rate in Nepal is very high," says Thapa. There are no official figures for the success rates of biogas plants in India, but Thapa says Indian visitors who have inspected Nepal's program say they have a below 60 percent success rate. In China, where the emphasis is less on gas than on fertiliser, the figure is even worse. It's probably also because donors abroad often build large plants to support a whole community. Explains Thapa: "In Nepal individual farmers actually buy plants. As a result they feel responsible and make sure it is well maintained."

BSP engineers are currently experimenting with biogas plants that can work in even colder regions in high altitude villages where deforestation is rampant. Biogas could be a solution for both cooking and heating. Above 2,500m it is too cold for microogranisms to break down slurry into methane. In 2001, BSP built two plants in Solukhumbu, with a greenhouse on top of the digester. This year more experiments will be carried out to integrate solar panels to heat underground digesters.

BSP program manager Sundar Bajgain explains: "It is a fine balance between trying out new ideas and keeping costs down." Whether or not BSP will be able to come up with an affordable high altitude plant, the potential for biogas in Nepal is still huge. Our total cattle and buffalo population is at least an estimated 9.3 million, and they theoretically produce enough dung for 1.4 million biogas plants. BSP aims to construct 200,000 new plants in the coming six years. "We've set up a loan and micro finance structure in order to reach poor people in more remote areas," says Bajgain.

All in all, biogas proves that a development effort based on a simple, practical idea, can yield excellent results. BSP recently obtained ISO certification, and by December, it will be legally independent from the Dutch aid group, SNV/Nepal which supported it. In the future, BSP probably will not need the financial support of Western donors anymore. And with the Kyoto Protocol, it is possible for Nepal to actually trade CO2 emission. Western countries that contaminate the environment way too much and have difficulty to keep within the limits set in Kyoto, can buy reduction of CO2 emission from countries that don't produce CO2.

Even though biogas plants produce methane, which is a more powerful greenhouse gas, most of it is burnt and its volume is negligible compared to emmisions from fossile-fuel burning cars. One biogas plant reduces CO2 emission by 4.7 tons per year, and the Kyoto trade-in for one ton of reduction can be up to $10. "Considering the increasing number of plants, we're talking about a lot of money," Bajgain says with a big smile. "The beautiful part is the money has to go back to the program which generated the reduction. The government can't buy guns with revenues. It would be enough to finance our whole program. The ball is now in the government's court."

Made in Nepal

The Nepali biogas plant design uses an air-tight underground digester where bacteria breaks down the raw material in the farm waste to produce methane. The reaction has to take place in the absence of oxygen, and these bacteria occur naturally in the cow's stomach. The gas contains up to 70 percent methane and 30 percent carbon dioxide.

The Nepali biogas plant design uses an air-tight underground digester where bacteria breaks down the raw material in the farm waste to produce methane. The reaction has to take place in the absence of oxygen, and these bacteria occur naturally in the cow's stomach. The gas contains up to 70 percent methane and 30 percent carbon dioxide.

A biogas plant consists of five main components. The required quantity of dung and water is mixed in the inlet tank (right) and digested in the digester. The gas produced in the digester is collected in the dome. The digested slurry flows to the outlet tank and ends up in the compost pit as the gas pressure in the dome forces the effluent out. The gas is tapped from the top of the dome with a pipe that goes to the kitchen.