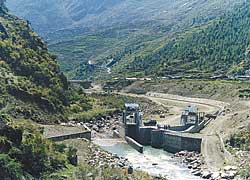

Last month, three Nepali power projects with substantial local rupee investments were tested and commissioned: Chilime (20MW) in Rasuwa, Piluwa (3MW) in Sankhuwasabha and Jhimruk (12MW) in Pyuthan.

Last month, three Nepali power projects with substantial local rupee investments were tested and commissioned: Chilime (20MW) in Rasuwa, Piluwa (3MW) in Sankhuwasabha and Jhimruk (12MW) in Pyuthan. Nepal's hydropower development took a wrong turn 25 years ago, and it has finally come back on track. Individual aid-funded projects are now being replaced by projects that enhance our own technical and financial capacity to meet energy needs. From the late 1970s onwards, foreign aid completely dominated the power sector. High-budget, glamorous, aid-funded projects like Kulekhani I and II, Marsyangdi, Kali Gandaki and even the ill-fated Arun III became much more attractive to politicians and policy makers than building smaller projects using local resources.

These mega-schemes were funded by multilateral banks or bilateral donors, and the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) effectively lost control over its hydropower strategy. The strict conditions of these donors meant that projects had to be designed and managed by international consultants and built by outside contractors. Not even Indian or Chinese companies, which were building much larger projects in their own countries, could pre-qualify for construction contracts in Nepal.

Unfortunately, these externally funded, designed and constructed projects did little to enhance national capacity. The projects were expensive, and the country was forced on a path of longterm dependency and unaffordable energy costs. People began to question whether hydropower was even an asset. The irony of one of the poorest countries in the world building some of the most expensive projects was lost on our policy makers and civil society.

It took 15 years and the restoration of democracy, when Arun III exposed the contradiction between the Nepalis' need for cheap electricity and the high cost of production of foreign-built mega-projects. Nepali engineers, economists and civil society finally started looking at cheaper, indigenous projects. Although initially met with skepticism, it has now become clear that only through locally-financed, locally-built and locally-managed smaller projects would the price of electricity in Nepal come down to affordable levels. Outside investment, it became clear, should supplement national expertise and resources. Not substitute for them.

Today, projects like Piluwa and Chilime are living proof that the paradigm shift in Nepali hydropower planning have brought real change. These and other projects have extensive involvement of both in-country financial institutions and technical manpower. And the beauty is their cost of electricity generation is $1,500 per kW, less than half that of larger aid-funded projects.

The success of the Chilime model is largely due to one man, Dambar Nepali (see interview). And it is such a success story that the management is already thinking of starting on the 26MW Upper Chilime next, and in future it wants to take on the 250MW Upper Tama Kosi for less than the per kilowatt cost of Chilime.

he Butwal Power Company (BPC), newly privatised in January 2003, is a consortium of Nepali and Norwegian investors who have invested Rs 952 million for 75 percent share of the company. The company owns Andhi Khola (5.1MW) and Jhimruk (12MW). BPC has rebuilt Jhimruk, and is selling energy to NEA at Rs 3.67 per kWh. The construction of Piluwa (3MW in Sankhuwasabha) and Syange (183 KW in Lamjung), undertaken largely by investors from the districts they are based in, were made possible under NEA's policy announced in 1998 to purchase energy from below-5MW hydro producers under a standard contract. The credit for this goes to Shailaja Acharya when she was Minister of Water Resources.

It is clear that the cost of construction of hydropower projects in Nepal depends strongly on the financing modality. The per kW construction costs of locally financed projects are lower than either large donor-funded projects or the International Independent Power Producers (IPPs).

Interestingly, the mode of financing and the contracting that goes with it has a much stronger impact on project costs than economies of scale. Larger projects financed through aid are the most expensive, followed by medium scale projects built by the international private sector and the least expensive are the smaller, locally financed projects.

One possible reason for the relative high cost of aid funded projects is that they are generally designed for storage (Kulekhani) or for daily pondage (Marsyangdi and Kali Gandaki), and in the case of Arun III there would have been a 120 km access road whose cost was also included in the project. Such projects incur higher civil construction and land compensation costs compared to run-of-the-river projects. However, it still does not explain the two-and-a-half times higher cost compared to the rupee financed projects.

Large aid-funded projects are very expensive partly because of the rigid conditions of competitive bidding to the highest international standards. These standards are so high that only a handful of companies in Europe, the US and East Asia even pre-qualify. Many are also bound by tied-aid rules under which equipment purchases have to be made from the donor country. With international IPPs, the cost comes from dollar loan financing at interest rates ranging from 8-13%, which is higher than Nepali rupee loans and have to factor in rupee depreciation, and their perception of the risks in investing in Nepal.

There are, therefore, three main reasons why locally designed projects are less expensive:

. The cost of capital borrowed from local banks is at its lowest point in many years.

. Developers had complete flexibility in where they source their equipment and how they pick contractors, and they can get the best prices.

. Smaller projects mean fewer technical complications and the ability to breakdown contracts into small components that could be bid out among a large number of competitive Nepali, Indian and Chinese companies.

Besides being cheaper, local investments also benefit the national economy through much stronger backward linkages in construction and manufacturing. Usually, it is only the equipment (25-40 percent of total cost) which has to be imported from overseas.

There is now plenty of evidence that Nepal's hydropower sector can attract substantial local investment both in equity and debt. Nine prominent Nepali business houses invested in the BPC, by far the largest privatisation so far in the country. Nepal is earning over $1 billion every year in remittances from overseas workers. Channeling just 10 percent of this will meet most of our hydropower needs.

Nepali consumers suffer among the highest electricity prices in the region. The cost to the consumers is ultimately dependent on the Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) signed by independent power producers with NEA. PPAs signed in dollars will cost the Nepali consumer around Rs 25 per kWh in 2010, while local rupee based PPAs would cost less than half because of contractual escalation in tariffs and rupee depreciation.

There are some things that need to be ironed out. At present, there is a large difference between the PPAs signed between NEA and various private producers, even those with full local investment. For instance, with escalation by 2012, the PPA tariff for Chilime will be Rs 7.55, for Piluwa Rs 4.35 and for Jhimruk Rs 6.57. There is no longer any justification for negotiating different prices for energy from each supplier for future run-of-the-river schemes under 25MW.

One of the big changes in the last 10 years is that Nepal's donors have finally realised that large projects have diseconomies that make them expensive for Nepal. The World Bank's recently approved Power Development Fund will be financing smaller projects in the under-30MW range.

Future support from the international community to Nepal's power sector will be most effective if it is used to support both NEA in the public sector, and private Nepali sector companies to increase their capability to build low cost, high quality projects. The hydropower sector in Nepal needs technical support and financing to carry out projects of the size that it can manage itself.