It will soon be a year since an elected prime minister was sacked and King Gyanendra took over the reins of power. There were questions about the constitutionality of that move, but the majority of people gave their king the benefit of the doubt last October because he vowed to restore peace. His handpicked government kept that promise, and by January a truce and peace talks were declared, justifying the royal move in the public eye.

It will soon be a year since an elected prime minister was sacked and King Gyanendra took over the reins of power. There were questions about the constitutionality of that move, but the majority of people gave their king the benefit of the doubt last October because he vowed to restore peace. His handpicked government kept that promise, and by January a truce and peace talks were declared, justifying the royal move in the public eye. Cast adrift, the political parties took nearly twelve months to muster enough unity and energy to counter the king's move, and even then it has been a relatively restrained agitation. The party leaders were unable to completely convince Nepalis that their anti-regression campaign was about restoring democracy and not about returning to Singha Darbar. And except for one Congress senior, the party that was in power for the longest period since 1990 showed scant remorse for squandering our hard-earned freedoms.

If the January cseasefire legitimised the king's October Fourth move, the breakdown of the truce three weeks ago and the dread of full-scale violence is now forcing a royal rethink. The same message is coming across loud and clear from the international community: there is no other recourse than for the palace and the parties to live and let live.

But we didn't really need foreign ambassadors to tell us what has been painfully obvious: forces guided by the constitution must be on the same side, otherwise it will bolster the side that doesn't believe in it. A parliamentary democracy within a constitutional monarchy governed by a reformed constitution should be a compromise acceptable to all. The trouble is that all three sides so far want a winner-takes-all formula, and have locked themselves into rigid positions.

This layered fight needs a sequenced solution, and the first order of business is to find an accommodation between the palace and the parties. All indications are that the king has returned with some new ideas, and with Mars now safely receding, signs are good that an accord can be reached. There are all kinds of options before the king: he can go back to pre-22 May 2002 and reinstate parliament, to pre-4 October 2002 and give Sher Bahadur Deuba back his job, to pre-30 May 2003 and accept Madhab Kumar Nepal who was the candidate endorsed by the five party alliance to suceed Lokendra Bahadur Chand or go back to 11 October 2002 and restart the game of musical chairs.

None of these options is going to resolve the Maoist problem overnight. But the king must chose the one that will hand power back to the peoples\' representatives. It is in his self-interest to re-erect the buffer that the monarchy needs to protect itself from the forces that want to overthrow it.

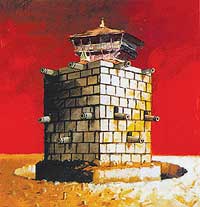

Despite their bravado and capacity to sow mayhem, the leaders of the Maoist movement know that this is not a war that will be easily won, if ever. They agreed to the truce in January to try to see if they could get what they wanted through negotiations. Negotiators derive clout from the threat of military prowess in the field, and the talks broke down on 27 August because the Maoists realised that the government side hadn't been softened enough. They are now taking the violence up a notch by threatening Fortress Kathmandu.

Sooner or later, as a new military balance of power is re-established, the peace process must resume. The only alternative is to fight on until there is no Nepal left.