Kathmandu has started feeling the terror that has stalked the rest of the country. In large parts of village Nepal, misery and death has become a way of life for those without the resources to move to Kathmandu's urban embrace.

Kathmandu has started feeling the terror that has stalked the rest of the country. In large parts of village Nepal, misery and death has become a way of life for those without the resources to move to Kathmandu's urban embrace. Author Khagendra Sangraula has written vividly about the villager caught in the middle, between the Maoists' constant threats and the army's occasional but havoc-making passage. He wrote of the situation a year ago. Today, the people are cowering more than they ever did, as the war enters a more brutal and unpredictable phase.

In many villages, teachers and health workers are often the only representatives of the state (if we can call them that) still left. They are regarded suspiciously by the Maoists of being supporters of the UML or the Congress, and by the army as Maoist sympathisers for willingly paying what is, in fact, a forced revolutionary tax equivalent to a day's salary a month. Yet these teachers and health workers in, say, Ramechhap or Rolpa have little choice but to stay to teach and treat so they can send some savings home to their families in Jhapa or Chitwan.

The villagers have little foothold left. Only those without resources and contacts in Kathmandu or roadhead towns remain in the villages. The Maoists hold the countryside except when the army marches through (sometimes in civvies, which only adds to the terror), so the villagers have no option but to submit to the rebels. This makes them 'accidental Maoists', as one writer has described them: at the mercy of government forces when they arrive wielding their SLRs and M-16s. Today across Nepal, trapped Nepalis are suffering psychological trauma on a mass scale.

Then there is the daily bloodletting in which the police, army and the Maoists are being killed. The army often catches innocents in its net, and the Maoists are exacting revenge against suspected informants. The impunity is near total.

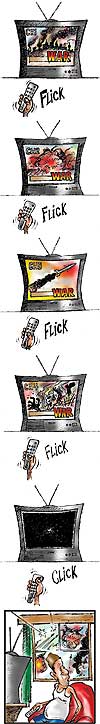

The Maoists love to coddle Kathmandu Valley because in its willingness to turn the other way, lies the opportunity to wreak havoc on the countryside. We know by now that images of dead bodies of foot soldiers, policemen, the Maoists and innocent villagers killed by rebel or army action doesn't outrage the capital. Kathmandu never felt the pain of the rest of Nepal.

But now, as the national infrastructure and Valley people are targeted by the desperate insurgents, the danger is that even those who would have mouthed liberal sentiments on human rights and Geneva conventions, are going to keep silent. Even more than before, they will look the other way.

At a time when the Maoists have given up their guise of being a political force, and when armed cadre stalk the hinterland with seemingly little control of their leaders, there is perhaps little sense in appealing to the good sense of the mercurial Prachanda or the argumentative Baburam, who once said that children, too, had a right to fight a revolution.

But perhaps we can still appeal to the army to be careful as it goes about this phase of the war. And the appeal would be this: please take care that you fight clean, that you stand by universal principles of humanitarian behaviour. This is because you represent much more than the Maoists ever can or will. It is your job to protect the people of Nepal, not pursue them.