It is always a surprise, and a little insulting, when people dismiss Nepali food as boring. That old joke about "dull bhat". Actually there is no such thing as 'Nepali food'-Nepal's cuisine is a composite of food experiences from across this diverse land with foods to suit the tropical tarai to the arctic Himals. Even if geography alone played a role in our eating patterns, it would logically follow that each region would have a cuisine particular to what was available. And Nepali cuisine has also been enhanced by trade, which has blended and blurred our culinary boundaries.

It is always a surprise, and a little insulting, when people dismiss Nepali food as boring. That old joke about "dull bhat". Actually there is no such thing as 'Nepali food'-Nepal's cuisine is a composite of food experiences from across this diverse land with foods to suit the tropical tarai to the arctic Himals. Even if geography alone played a role in our eating patterns, it would logically follow that each region would have a cuisine particular to what was available. And Nepali cuisine has also been enhanced by trade, which has blended and blurred our culinary boundaries.

Newari  Starting right here in the Kathmandu Valley, the Newars have had links with Tibet and China for centuries. While the ancient salt route is dying out today, the osmosis of culture and taste is still alive in the ubiquitous momo-cha. It's the smaller, spicier version of the Tibetan momo that can be found in the Valley's gallis. But Newari culinary traditions are vibrant. Most Newars can reel of the dishes in the samme bhwe, the traditional feast: chiura, shia baji - beaten rice, haku musya - black soyabean curry, bhuti - soyabean, palu, loba - marinated ginger and garlic, chwela - boiled and spiced mince meat, wala tau gu alu - fried potatoes, woh - black dal fritters and chatamari - the Newari cross between a pizza and a dosa. All of it is eaten off taparis, ingenious disposable leaf plates. Judging from the average Newari clan feast, it's a blessing there is no washing up to contend with.

Starting right here in the Kathmandu Valley, the Newars have had links with Tibet and China for centuries. While the ancient salt route is dying out today, the osmosis of culture and taste is still alive in the ubiquitous momo-cha. It's the smaller, spicier version of the Tibetan momo that can be found in the Valley's gallis. But Newari culinary traditions are vibrant. Most Newars can reel of the dishes in the samme bhwe, the traditional feast: chiura, shia baji - beaten rice, haku musya - black soyabean curry, bhuti - soyabean, palu, loba - marinated ginger and garlic, chwela - boiled and spiced mince meat, wala tau gu alu - fried potatoes, woh - black dal fritters and chatamari - the Newari cross between a pizza and a dosa. All of it is eaten off taparis, ingenious disposable leaf plates. Judging from the average Newari clan feast, it's a blessing there is no washing up to contend with.

There are other dishes that are eaten almost exclusively at home. Swo is similar to Scottish haggis, only better. Goats lungs are force-filled with a batter of flour, eggs and spices. It is boiled, sliced and fried, to be served hot with a touch of salt and pepper, washed down with a palate cleansing shot of ela or tho, homemade firewater.

If the English have their blood sausages and the French their escargots, the Newars indulge in yanghu yi hau or tuyu yi hau, a choice of either white or red savoury blood pudding. When it comes right down to it, everything does not taste like chicken after all. If you want to eat like the locals, and are not fortunate enough to snag an invite to a bhwe, follow your nose behind Krishna Mandir at Patan Durbar Square to Ho na cha, a Newari food haven.

Rana  On a x-y axis, Rana food would be at the other end of Newari cuisine. The only thing they'd have in common would be unrefined mustard oil. It all began in the 1840s when Jung Bahadur returned from his victorious campaign in Lucknow with several khansamas in tow. The Muslim cooks specialised in the rich Mughlai tradition and divulged their secrets to the bajais, the only ones allowed to cook for royalty. What came about from this chain of culinary art was a distilled version that rejected heavy flavours and oils but embraced the kebab to create sekuwa. Ranas did not eat chicken, especially after the sacred thread ceremony for boys. But being meat lovers, their meats had to be properly cleaned, spiced and cooked.

On a x-y axis, Rana food would be at the other end of Newari cuisine. The only thing they'd have in common would be unrefined mustard oil. It all began in the 1840s when Jung Bahadur returned from his victorious campaign in Lucknow with several khansamas in tow. The Muslim cooks specialised in the rich Mughlai tradition and divulged their secrets to the bajais, the only ones allowed to cook for royalty. What came about from this chain of culinary art was a distilled version that rejected heavy flavours and oils but embraced the kebab to create sekuwa. Ranas did not eat chicken, especially after the sacred thread ceremony for boys. But being meat lovers, their meats had to be properly cleaned, spiced and cooked.

Gautam SJB Rana, who owns Baithak, the only Rana food restaurant in the Valley is not only a foodie but a connoisseur who goes into raptures over bafa ko bandel, (pic, right) a deceptively simple sounding but exceptionally difficult dish to execute. A wild boar is boiled and its hairs plucked by tweezers. It is then steamed on a bed of tej leaves. The fragrant meat is wrapped in muslin cloth and allowed to rest overnight. The next day it is sliced into bite sized pieces and served with salt and chilli. Somewhat conspiratorially, Gautam reveals how many Ranas judge a feast not by the lavish variety, but solely on the bafa ko bandel.

Fifty-five-year-old Durga Gautam used to be a bajai in the kitchen of Prabhu Sumshere. From the age of 14, she served there for nearly two decades, turning out Nepali style pulaos, the unique panchamukhi dal that incorporates five different lentils and bari, chicken meatballs that no Italian mama could hope to rival.

Sherpa

More than the gourmet experience, nourishment is the foundation stone of Sherpa cuisine. For generations the Sherpa worked their arid terraces for potato, barley and buckwheat. The harsh, high terrain and cold climate called for hearty stews, and shyakpa is the perfect example. While Sherpa rice wine, chang, has many converts, their tea is still an acquired taste-hot and milky, fortified with yak butter and salt that most first timers are advised to think of as soup. When tsampa, barley flour, is thrown into the mix you end up with a very nutritious porridge that is good trekker fuel. Palmo Khampa's restaurant, Dechenling, specialises in Tibetan and Bhutanese food, both close kin to Sherpa cooking. An old Tibetan cook trained her staff, and "it's what we eat at home," says Palmo. Another definite link between Tibetan and Newari food shows up on the menu-lowa is very similar to swo. The in-house specialities are dapao, minced meat steamed in soft dough buns, spicy hot garlic potato eaten with tingmo, meaning 'cloud momos' for their soft roundness, and shabhale, meat stuffed into flaky pastry and deep fried.

Thakali

When it comes to dal-bhat, let it be said that no-one does it better that the Thakalis of lower Mustang. As traders between India and Tibet, the Thakalis adapted dishes and together with local favourites, created a culinary tradition all their own. It's a huge compliment to Rekha Bhattachan that since 1997, locals have been flocking to Tukkeche Thakali Kitchen to eat dal bhat. The secret to her dal is slow cooking in an iron pot, a Rana tradition too, and the ratio of tumeric to ghiu for a green colour peculiar to Thakali dal. Unlike midhill Nepalis, Thakalis pay close attention to the visual appeal and presentation of food. "You'll never find a potato dish next to cauliflower," explains Rekha. "It will be something green, like spinach." Bowls are arranged to the right of the plate with the dal closest, followed by soup and an array of meat and vegetable dishes. For the truly adventurous, Rekha suggests a typically Thakali item: lyetpo khu, head of goat soup-all organs included-diced into small pieces and cooked with timur, salt, garlic and chili powder.

For adventurous vegetarians there is the joy of kinema and gundruk. The first is fermented, and to be honest rather foul smelling, soyabeans that taste divine with Bombay duck in a thick tomato paste. Gundruk is fermented vegetable greens, usually radish tops, that makes a sour soup which is often a substitute for dal. Both feature in Rai and Gurung kitchens. During the full moons of Ubhauli (April-May) and Udhauli (November-December) the Rais have their sakela puja, a ritual for good weather and abundant harvests. The sacrificial chicken is made into wachhippa with ash of burnt feathers, ginger, chili and rice that is washed down with raksi.

Sweet nothings

The agrarian people of the fertile plains in the south make some of the best sweetmeats. During Chhath most households in the tarai make thakuwa, a deep fried dish made of wheat flour and sweetened with cane sugar. During Holi, malpua, a batter of flour is made with milk, spices, sugar and coconut and deep fried, comes into its own. Then there is the special sel roti, made of rice flour, milk, sugar, ghiu and cinnamon, which is eaten during major festivals like Dasai and Tihar. Yomari is a unique Newari sweet, almost like a Japanese moon cake, sticky rice case stuffed with a mixture of jaggery and sesame. When all else fails, there is curd, thick and rich like the famed Juju dha from Bhaktapur. It is the base for perhaps Nepal's most popular dessert-sikarni. Curd is tied up in muslin overnight and then sweetened, spiced with cinnamon and cardamom, and served chilled with slivers of blanched almonds.

ETC

Every fashionista knows that accessories pull an outfit together, and so it is with the wide variety of condiments served with most Nepali food. Momos come with a fiery dip made from the red hot dalle khursani. Depending on what type and how dal bhat is made, you could have anything from alu ko achhar, spiced boiled potatoes cubed in yoghurt and sesame, mula ko acchar, labour intensive but delicious radish pickles in either mustard oil or brine, tamatar ko achhar, a thickly reduced tomato paste of garlic, ginger, green chili and onions. As longtime Nepal resident Dubby Bhagat remarks, "Nepal has as many pickles as France has cheeses." Quite.

If, like us, you're too impatient to make your own, the WEAN Co-operative has a wide selection of pickles that are found on tables as far away as Germany and Japan that get a thumbs up from Nepali consumers. And if you feel inspired to cook up some genuine Nepali food they also have ingredients like bhatmas and masaura.

Where to eat Nepali  Kathmandu is a melting pot of cultures and cuisines. In this great melange there still are many places where you can sample a diverse range of Nepali food.

Kathmandu is a melting pot of cultures and cuisines. In this great melange there still are many places where you can sample a diverse range of Nepali food.

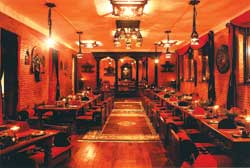

Bhanchha Ghar has become synonymous with a traditional Nepali culinary feast, since 1989. "Our food is a total Nepali food experience," says Kishore Raj Pandey. Over in Jamal, Kathmandu Kitchen offers exquisite chatamari served with tomato and cilantro achar. You might even catch a Tamang jhankri dancer eat fire, the ash from which is traditionally used to cure the sick. In Naxal, in the quiet retreat of Wunjala Moskova you can sample more Newari and even Russian delights. Especially popular are the savoury marinated bite sized chwela. In the heart of town in Dilli Bazar is Bhojan Griha in a Rana house built 150 years ago. Short of going to Mustang, your best bet for Thakali food is Tukkeche Thakali Kitchen on Darbar Marg.

For true Sherpa or Tibetan food you just can't go wrong with Dechenling Garden tucked in Thamel. The chili factor is pretty high so keep a chilled beer handy. Must samples are the ama dhatsi and tingmo. An all time favourite, also in Thamel, is Hotel Utse, still hailed for the best momos this side of the Friendship Bridge.

Around the Patan Darbar Square there are a number of restaurants that serve Nepali food. In Mangal Bazar, Layeku Kitchen is ideally located for stunning views and great food. But if you'd rather be in the centre of things, Patan Museum Caf? has a very good Nepali thali within the quiet confines of the actual darbar. For a regal dining experience that doesn't cost a king's ransom Baithak at Baber Mahal Revisited is quite literally the only place to go. Last but not least, if you want elaborate presentation and taste, book ahead at Krishnarpan at Dwarika's Hotel (pic,right) for a 16 course dinner that will make everyone well and truly abandon the idea that Nepal's cuisine is dull.