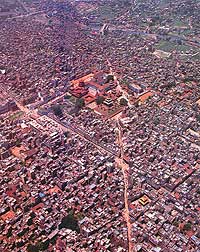

The British historian, Perceval Landon, came to Kathmandu Valley in the 1920s, and wrote the famous lines describing Kathmandu as a city with more temples than houses, and more idols than people. Sadly, this epithet no longer applies. The temples have long since been outnumbered and rendered invisible by concrete buildings. And at present rates of growth, the Valley's 1.5 million population is expected to double in 12 years.

The British historian, Perceval Landon, came to Kathmandu Valley in the 1920s, and wrote the famous lines describing Kathmandu as a city with more temples than houses, and more idols than people. Sadly, this epithet no longer applies. The temples have long since been outnumbered and rendered invisible by concrete buildings. And at present rates of growth, the Valley's 1.5 million population is expected to double in 12 years.

Kathmandu\'s exceptional architectural legacy was recognised as a World Heritage Site in 1979 by Unesco. It was more than just a tourist attraction-the Valley had a vibrant, living culture with a unique urbanscape and architectural heritage. Anyone flying into Kathmandu today will immediately see that things haven't turned out as planned at the seven sites set aside by Unesco: the three Durbar Squares at Hanumandhoka, Mangalbazar and Bhaktapur, the stupas of Boudhanath and Swoyambhunath, and the temples of Pashupatinath and Changu Narayan.

On 4 July this year, Kathmandu was placed on the Unesco list of endangered sites-right alongside the Bamiyan Valley in war torn Afghanistan. Uncontrolled urban development, not the guns of war, has ravaged our heritage. Kishore Thapa, deputy director general of the Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, admits that although there are strict zoning laws and building codes, the problem lies in enforcing them.

The fight to save Kathmandu's heritage needs more than controlling urban expansion. Restoration is costly, labour intensive and time-consuming. With every crumbling temple it is not just architecture that is at stake, but also the countless wooden and stone carvings and idols that they house. Thankfully, there are the first signs of a renaissance in conservation of what is left of the towns in the Valley.

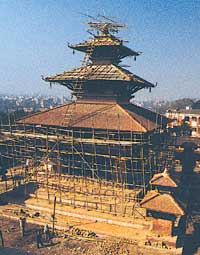

Local guthis, altruistic individuals, conservation groups and even a government department are serious about restoration. The Nepal Heritage Society, founded in 1983, strives to create public awareness, so that the people of Kathmandu understand the importance of conservation. This can't be done without community support so they conduct public meetings to keep people informed, like they did about the newly-renovated Charumati Stupa in Chahabil that was restored by the Central Conservation Laboratory for Cultural Heritage, a branch of the Department of Archaeology (DoA).  When the DoA took on the job of restoring the Tripureshwor Mahedev Temple (top, right), originally built by Queen Tripura Sundari in 1818, the three-tiered pagoda style roof had caved in. Repairing the roof and retouching the beautifully carved eaves took two years, now the pati around the temple is near completion too. The department is also working on the Taleju Bhawani Temple in Bhaktapur, and has most recently sought to conserve and restore the murals on the four outer walls of the Bagh Bhairab temple in Kirtipur. Sadly, the department is under-funded and its efforts and expertise are not nearly enough to restore the 16th century paintings that depict scenes from the Mahabharata.

When the DoA took on the job of restoring the Tripureshwor Mahedev Temple (top, right), originally built by Queen Tripura Sundari in 1818, the three-tiered pagoda style roof had caved in. Repairing the roof and retouching the beautifully carved eaves took two years, now the pati around the temple is near completion too. The department is also working on the Taleju Bhawani Temple in Bhaktapur, and has most recently sought to conserve and restore the murals on the four outer walls of the Bagh Bhairab temple in Kirtipur. Sadly, the department is under-funded and its efforts and expertise are not nearly enough to restore the 16th century paintings that depict scenes from the Mahabharata.

Surya Kumari Manandhar, a restoration artist who worked at Bagh Bhairab, says the department's work consists of repairing cracks and holes with plaster of paris, cleaning off the dirt and gently retouching the paintings without reinterpreting the original colours and designs. Despite the hard work, the paintings are still in a deplorable condition. Worse, the community around the temple shows little interest in the work that went on for over six months.

Five elderly Kirtipur gentlemen sitting outside a shop near the Bhairab temple entrance shrugged their shoulders when asked what they thought. "It's outsiders who did it," one of them said. The pujaris who perform monthly rituals at the temple were neither curious nor pleased with the restoration. The murals had become slightly brighter, they said without interest. This apathy needs as much work as the actual process of renovation and conservation.

It's not hard to imagine Kathmandu as it should and could have been, if only we had taken a more active interest in our surroundings. Dwarika Shrestha and his family were ones who did, rescuing and reusing antique friezes and windows from torn-down buildings to build the award-winning Dwarika's Hotel. Shrestha believed in community contribution and involvement, and his family is now carrying on his life's work to restore other nearby temples. Dwarika's doesn't actively collect wooden carvings, discouraging the practice of dismantling houses purely for the advantage of selling its precious wooden windows and supports.

Ram Mandir, just in front of Dwarika's, was renovated with the combined effort of the Dwarika team, consisting of architect BD Pokhrel, artisans from its workshop and the municipality. Today, it is also enthusiastically supported and maintained with the help of the local community of Battis Putali, named after the 32 carved sculptures that adorn the interior of Ram Mandir.

Ram Mandir, just in front of Dwarika's, was renovated with the combined effort of the Dwarika team, consisting of architect BD Pokhrel, artisans from its workshop and the municipality. Today, it is also enthusiastically supported and maintained with the help of the local community of Battis Putali, named after the 32 carved sculptures that adorn the interior of Ram Mandir.

Another encouraging example of growing local awareness and involvement in heritage conservation is the ongoing restoration of the small but elegantly proportioned Ugrachandi Temple at Jawalakhel. The local guthi there raised funds to restore the temple from various bhojs during important festivals. They also took a loan that they plan to repay by money earned from renting out the newly renovated and very pleasing Newari style banquet hall behind the temple. "Our ancestors set up guthis for each temple so they could maintain and sustain themselves for posterity, most of them have frittered away their assets, but we need to facilitate a resurgence of the old guthi spirit," says Sangita Shrestha of Dwarika's.

Perhaps the best known example of self-sustaining conservation is Patan Museum, once a medieval palace in the heart of Patan Darbar Square, and now a world class repository for Hindu and Buddhist artifacts. The museum itself is a bracing example of restoration, and bears eloquent testimony to our cultural and architectural heritage. It raises funds from entry fees, a restaurant, an exhibition hall and a museum shop-proving that heritage conservation combined with revenue generation is the way to go.

With more examples like this, and given political will and more alert communities, there is reason to be hopeful that Kathmandu will be struck off Unesco's endangered listing and become a secure World Heritage Site again. We must protect our sacred spaces, from ourselves.

True to the original

Staying true to the original, which often requires meticulous research, challenges conservation organisations as much as the pressing concern of insufficient funds. Rohit Ranjit, one of the chief architects for the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KPVT) recalls the hard work that went into renovating the Indrapur temple in Kathmandu Durbar Square. When it was destroyed in the earthquake of 1934, Juddha Shumsher had it reconstructed but unfortunately, the roof was redone without much regard to the original (see pic and drawing, left). When the KVPT began to restore the Indrapur temple, which had once again started to crumble, they redesigned it after tracking down rare pre-1934 photographs (below, right). Today, it stands close to its original glory.