Tenzing your immortality is assured.

Tenzing your immortality is assured.

Your name is written in gold.

You will always be honoured

for 29 May

when the highest peak in the world

bowed to kiss your feet.

You reached the top,

looked down at the world,

and helped others climb.

Tenzing, the world smiles

with pride at you.

Fifty years ago, Nepal's folk-singer-in-chief, Dharma Raj Thapa wrote those lines after Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Everest with his New Zealand counterpart, Sir Edmund Hillary. Today, the octogenarian singer and writer feels that Tenzing never received enough respect or credit for his contribution in making the Sherpa community and Nepal famous around the world.

Legend has it that Tenzing's real name was Namgyal Wangdi but a rimpoche changed it to Tenzing Norgay, meaning 'fortunate', a prophecy that came to happy fruition when he reached the summit of Sagarmatha and became a celebrity. From then on, he became the favoured son of the Sherpa people, their ambassador to the outside world. Tenzing's career in high altitude adventure closely reflects the hardships he went through to achieve the status he enjoys today.

But an increasing number, among them lyricist Thapa, believe Tenzing, the man and the climber, has been overlooked in the fanfare of commemorating the first successful human ascent of Mt Everest. A seminar organised on Tuesday by Himal Association and The Mountain Institute was an occasion to pay tribute to the man who has often been sidelined in the media.

Forestry expert Lhakpa Norbu Sherpa who has been studying Tenzing's childhood, revealed a different side to the mountaineer.

Born in a Tibetan village in Kharta Valley in May 1914, young Tenzing's early childhood was spent in severe poverty and hardship. Life on the high plateau where his parents were wage herders was so difficult that only six out of 14 of Tenzing's siblings survived into adulthood. He made the long journey on foot with his mother and brothers across the Himalaya to Thame valley in Nepal in search of a better life.

Life as a yak herder in Khumbu was slightly easier, but he later migrated to Darjeeling in India at the age of 18 to try to get a job as a mountaineering porter. Many Sherpa lads were headed that way because of the demand from British expeditions trying to explore and climb Everest from the north. Tenzing's first break was the Everest Expedition led by Eric Shipton in 1935, and he made several other unsuccessful attempts at the summit.

In Kharta, Tenzing's family was ill-treated and exploited because they belonged to the lowest economic and social strata. Some say this was why he chose not to return to Tibet, even though his father, Minga, remained there and died shortly after the family migrated. Tenzing married thrice, all of them were Sherpa women. He became an adviser and the guiding spirit at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI) after his appointment in May 1976.  Sherpas make up one-fourth of those who climbed Sagarmatha and one-third of those who died there, but they rarely merit a mention anywhere. But geographer Harka Gurung says Tenzing was always different from other Sherpas. "He had a different perspective on the whole business of climbing. For one thing he understood the Western concept of 'earning a name'."

Sherpas make up one-fourth of those who climbed Sagarmatha and one-third of those who died there, but they rarely merit a mention anywhere. But geographer Harka Gurung says Tenzing was always different from other Sherpas. "He had a different perspective on the whole business of climbing. For one thing he understood the Western concept of 'earning a name'."

Although he spoke seven languages, Tenzing never learned how to write but dictated his books that provide a timeless account of an era when the high Himalayan frontiers were still unexplored. In his autobiography Tiger of the Snows, The Autobiography of Tenzing of Everest he says, "It has been a long road...from a mountain coolie, a bearer of loads, to a wearer of a coat with rows of medals who is carried about in planes and worries about his income tax."

Two major points of controversy surrounding Tenzing are who got to the top first and the matter of his nationality. With regard to the first, in his autobiography Tenzing writes, "A little below the summit Hillary and I stopped. We looked up. Then we went on. The rope that joined us was thirty feet long, but I held most of it in loops in my hand, so that there was only about six feet between us. I was not thinking of 'first' and 'second'. I did not say to myself, 'There is a golden apple up there. I will push Hillary aside and run for it.' We went on slowly, steadily. And then we were there. Hillary stepped on top first. And I stepped up after him." Throughout his life he maintained they climbed the mountain as a team. The discrepancy probably arises from a press statement following the summit where Hillary wrote they made it "almost together", adding to the speculation.

And then there is the detail of his nationality. After 29 May 1953, everyone was keen to embrace him. "Both Nepal and India needed a hero and a role model during a time of dramatic political changes," says writer Deepak Thapa who has been researching the life of Tenzing.

When Tenzing travelled across the Himalaya in search of a better life, he did so with no regard to political boundaries. American mountaineer Ed Webster's biography of Tenzing Norgay, Snow in The Kingdom created quite a stir when it said he was born in Tibet instead of Thame as believed earlier. Webster says both Sir Hillary and Lord Hunt, the leader of the1953 expedition, believed he was born in a remote mountain village in Nepal but the truth was concealed to avoid embarrassing India.

The fact that Tenzing eventually chose to settle down permanently in Darjeeling where he lived till his death in 9 May 1986 must have felt like a rejection to many nationalistic Nepalis. "Tenzing had a simplicity and humility about him but even then he must have felt eclipsed by the adulation the world showered on Edmund Hillary," says Lhakpa Norbu. He points out that while Sir Edmund Hillary was granted an honorary Nepali citizenship earlier this week, Tenzing-who deserves the equal honour-has been largely ignored. "If the Nepali government wants to honour my father with an honorary citizenship we will welcome it," said Jamling Norgay, Tenzing's son, "but he was a personality beyond any political boundary."

For Brian Penniston of The Mountain Institute, the point about nationality is moot. He says: "Birds don't have passports."

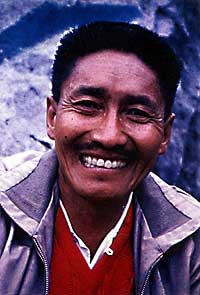

Gyalzen and Kanchha

Gyalzen Sherpa, 84, and Kanchha Sherpa, 71, were contemporaries of Tenzing Norgay. The sirdar trained and housed them in Darjeeling, and was instrumental in finding them jobs and promoting them from coolies to high altitude porters, opening the door for them to becoming sirdars themselves. Gyalzen and Kanchha were also a part of the British 1953 expedition with Tenzing.

The two accompanied Hillary on a horse-drawn carriage this week, just as Tenzing himself did in 1953. Both were ecstatic. They are dazzled by the pomp and ceremony of the Everest Golden Jubilee celebrations, and say this is the first time Nepal has feted their part in the success of the expedition. With pride they speak of the time Queen Elizabeth II awarded the whole team medals and Rs 500 each in cash.

As a child Kanchha was used to travelling the high passes to Tibet with his trader father. "Poverty pushed us into difficult jobs and at that time we had no alternatives," he says. In the 1953 expedition he transported food, set up tents and acted as a liaison between the porters and their employers. With a tinge of regret, Kanccha says he was never considered a climber although he made it to the South Col six times.

Gyalzen nods his head in sympathy but thanks the mountain goddess for the change in fortune of Sherpas like him. "What does remain the same is the style of mountaineering despite the increase in facilities," says Gyalzen, recalling when Sherpa porters were paid less than Rs 8 a day, Rs 10 if you were going up to South Col.

Khumbu has changed beyond the imagination of Gyalzen and Kanchha: the population has almost tripled, electricity and piped water is available and the staple diet has moved from millet to corn and now rice. Many are still poor, but tourism has brought in money and more opportunities. Today Gyalzen is one of the richest people in Namche Bazar, and his children do not need to risk their lives on the mountains. He has been on several Everest expeditions with Swiss, British and Indian teams between 1952 and1965, but confesses the most interesting one by far was in 1956. "We set out to look for a yeti, but found nothing," he says with a smile.

Gyalzen Sherpa(Left), Kanchha Sherpa(Right)