My father, Tenzing Norgay Sherpa, discouraged his children from becoming mountaineers because it was dangerous. He told us he became a mountaineer so we wouldn't have to. He knew, since he and Edmund Hillary were the first men to reach the top of Mt Everest in 1953. But I had dreamed about climbing Mt Everest ever since I was six-years-old.

My father, Tenzing Norgay Sherpa, discouraged his children from becoming mountaineers because it was dangerous. He told us he became a mountaineer so we wouldn't have to. He knew, since he and Edmund Hillary were the first men to reach the top of Mt Everest in 1953. But I had dreamed about climbing Mt Everest ever since I was six-years-old. In 1996, David Breashears, the leader of Mt Everest IMAX Expedition, was making a documentary about the Everest region, and he offered me a central role in it. Once we were in the mountains, things quickly began to go wrong. On 10 May, around three in the afternoon, we heard over the radio that many of those who were ahead of us were finally on top. But this was not good news. Sherpas radioed to say that only one or two climbers had returned from the summit and many were missing. Higher on the mountain where the climbers were floundering, a fierce blizzard had developed.

At Base Camp, ten different expeditions merged into one huge rescue station. In those 48 hours, we helped many survive their ordeal, but not all. After the helicopter flew out with the casualties, we assembled at Base Camp to recuperate and make preparations for our own attempt on the summit.

On the South Col, at Camp IV, our final rest before the climb to the top, after five hours of sleep, I woke up at eleven at night. The weather appeared ideal. The wind, which can be the curse of climbing, was gentle, like a refreshing breeze; it was calm and quiet all around. I felt this mild weather was a good omen.

On the South Col, at Camp IV, our final rest before the climb to the top, after five hours of sleep, I woke up at eleven at night. The weather appeared ideal. The wind, which can be the curse of climbing, was gentle, like a refreshing breeze; it was calm and quiet all around. I felt this mild weather was a good omen. For the next eight to ten hours, I was going to have to use every resource, every trick I had learned as a climber-this was the final test of all my years of learning. It was going to be climb, crawl, clutch, trudge a few steps, pant for breath and rest for a few seconds, and then start all over again using hands, feet, ropes and axe.

Among these massive mountains, I was nothing. A splinter that could be blown away by a whiff of breeze. And I said my prayers, especially when I suddenly came upon the dead body of Scott Fisher, one of the guides who had died, below the Southeast Ridge (27,500 feet).

Throughout the climb, I felt strong and confident. I thought of my father, of course. He had been on this mountain 43 years ago. I felt his spirit and his support. That is why I knew in my heart, "This is it! I will be on top too!" I knew I was doing well, yet at the same time, I felt anxious. I just wanted to be on top. But I told myself to be careful. You look to one side, you see Tibet, and on the other side, you see Nepal, and each a scary, sheer drop of 8,000 feet.

When I arrived at the South Summit, I was just 300 feet from the top, but I still couldn't see it. I then negotiated the treacherous traverse to get to the Hillary Step, a very precarious spot because you are totally exposed to the elements. I took care of that one too, and I began to think, well, yes, I've now seen and climbed these landmarks I'd heard so much about. But where was the top?

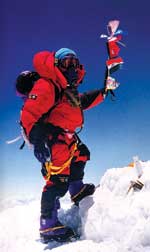

With renewed strength and spirit, I continued. I realised I was on the summit when I saw the prayer flags, left there by Sherpas before me. (That is me in the picture, inset, left, and my father in 1953.) I saw David and gave him a hug. I thanked him because he had made it possible for me to fulfill my childhood dream. I looked around. The summit sloped gently. You could fit twenty people comfortably. The view was stunning. I felt I could see everything, everywhere stretched out far, far away and far down below-little puffs of clouds and gleaming Himalayan peaks, all beneath my gaze. Then I cried, I was so happy. I was now the ninth person in our family to summit Everest.

I thought about my parents and prayed. I scattered some rice grains in the air and did puja. I left a prayer flag, a khata, pictures of my parents and His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Then I raised the flags of the United Nations, India, Nepal, USA-and Tibet. It was the first time since 1959 the national flag of Tibet had been unfurled on its own soil without fear of persecution, and I felt very proud. Finally, I left a small toy of my daughter's, just as my father had done.

I also felt truly humble and grateful. I said "thu chi chay" (thank you) to the Goddess Chomolungma and asked her to get me down safely. A foreigner sees a mountain and wants to climb it because it is the highest or the most difficult. He wants to conquer it, subdue it. For me and the Sherpas, climbing a mountain is a pilgrimage because the mountains are sacred to us. That was why I felt humbled, and that was why I cried. The Goddess Chomolungma granted my wish of a lifetime.

\'In My Father's Footsteps\' was first published in Travelers' Tales Nepal, collected and edited by Rajendra S Khadka, and published by Travelers' Tales, Inc, San Francisco. For copies of Travelers' Tales Nepal and the recently released Travelers' Tales Tibet email: [email protected]

\'In My Father's Footsteps\' was first published in Travelers' Tales Nepal, collected and edited by Rajendra S Khadka, and published by Travelers' Tales, Inc, San Francisco. For copies of Travelers' Tales Nepal and the recently released Travelers' Tales Tibet email: [email protected]