The irst Saturday of May was dry, windy and desolate, like any other day at this time of the year. A disquiet peace hung in the air, a lull before an impending storm. But the people standing in the queue appeared to be too desperate to care about the risks ahead. They lined up the street from the gate of Dasrath Rangshala to the traffic roundabout at Maitighar, waiting patiently to get a pass that would entitle them to be interviewed for a job in South Korea.

The irst Saturday of May was dry, windy and desolate, like any other day at this time of the year. A disquiet peace hung in the air, a lull before an impending storm. But the people standing in the queue appeared to be too desperate to care about the risks ahead. They lined up the street from the gate of Dasrath Rangshala to the traffic roundabout at Maitighar, waiting patiently to get a pass that would entitle them to be interviewed for a job in South Korea. Apparently, people have begun to vote with their feet in full force. The credibility of the king's direct rule was suspect from the day it began on October Fourth last year. Now the urge to get away is getting stronger as the government of king's nominees seems to be capitulating to the Maoists in order to keep itself well entrenched in Singh Darbar.

Despite the plethora of propaganda pieces on 'New Democracy' churned out by Maoist ideologue Baburam Bhattarai, no one has any illusion about their future in a dictatorship, be it proletariat or elitist. Forms may look different, but the content of Prachandpath and the rediscovered Mahendrapath of the Panchayat era are strikingly similar. So those that weren't in the queue last week were protesting out in the streets. The struggle against an unjust peace has begun in different forms.

Nepalis know what it is like to live under a totalitarian regime. The early seventies were the halcyon days of the Panchayat: bright King Mahendra buttons and little pink books on the merits of the Back to the Village Campaign were used as tools to terrorise the masses. Any one could be picked up and put behind bars by the authorities under the specious suspicion of being "anti-national".

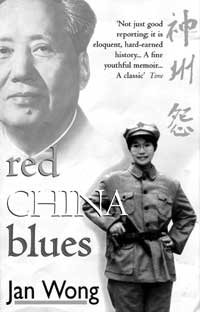

From Jan Wong's accounts of life in the People's Republic of China during the heydays of the Cultural Revolution, it appears that the lot of common Chinese under the dictatorship of the proletariat was no better. In many ways, it was worse, because an average Chinese had no way of getting away while even the poorest of Nepalis could freely use the option of trekking down to India in search of a job and security. In Mao's China, forget migration, people needed proper authorisation and special permission to visit "public parks on national holidays".

Wong begins her book by describing the pathetic condition of Mao's grandson who spends his time in a hospital flipping channels and dreaming about studying Maoism in the United States. The government won't let him out of the country, because as the over-weight Mao Xinyu explains to the author, "They are afraid I'll go out and my thinking will change. Or I won't come back."

A Canadian of Chinese descent, Jan Wong went to Mao's China in 1972 in search of an alternative world, if not the utopia itself. She enrolled at the Beijing University when the campus was still largely empty. But it didn't take her long to realise that her dreamland was a fool's paradise, a hermetically sealed Maoist bubble where campaigns against Beethoven were justified on the ground that the long-dead musician was guilty of "composing bourgeois music".

Wong was in Beijing as a student during the first Tianamen Carnage of 1976 when some of Zhou Enlai's mourners were beheaded because Mao explicitly forbade the use of guns in the use of "necessary force" to crush the "counter-revolutionary rebellion". She was there again at the time of the Tianamen Massacre thirteen years later, this time as a journalist. Comparing the two as a writer, she has this to say, "Both protests began as disguised mourning for a senior Communist official. Both crackdowns coincided with purges at the top. Both times, the victims were labled counter-revolutionary and the death toll was a state secret. The only difference was that, in 1976, Deng was the victim; in 1989, he gave the order to shoot to kill."

There is a strange sort of nostalgia in the first and second part of the book. Wong longs for her lost youth in chapters like 'Pyongyang Panty Thief' and 'Matchmaker' with sardonic wit. Describing her days of courtship, she writes, "I began seeing Norman regularly. Did we date? Go to Disco? Take in a revolutionary opera? No, we joined a study group and read all three volumes of Das Kapital."

The text of the third part on 'Paradise Lost' and the final part titled as 'Paradise Regained' is full of racy journalese and judgemental observations. But there is never a dull moment as the writer explores different layers of her own disillusionment. Denouement is reached when she finally realises that Canada is "far more socialistic than China has ever been, with its free public education, universal medicare, unemployment insurance, old-age pensions and government funding for television ads against domestic violence".

This book deserves to be translated into Nepali and made required reading for every angst-ridden school dropout who is duped into believing that dictatorship is a necessary condition for utopia. To a distraught person, the prospect of escaping to Korea may appear tantalising, but totalitarianism in every form must be fought if the root cause of the fear of future is to be removed. Running away is no solution.

Desperate souls seldom gain paradise, determined ones always do. This account of Jan Wong's journey through her life once again reiterates the continuing relevance of that old dictum.