Toni Hagen knew Nepal inside out. Literally. As a geologist, he put together the first 3-D jigsaw puzzles of stratigraphic cross-sections of the Nepal Himalaya. He took 15 years to trek 14,000 km across the length and breadth of a roadless country, analysing rock outcrops and mapping the orogenics. But the more he studied Nepal, the more Toni Hagen found his interest veering away from rocks to people.

Toni Hagen knew Nepal inside out. Literally. As a geologist, he put together the first 3-D jigsaw puzzles of stratigraphic cross-sections of the Nepal Himalaya. He took 15 years to trek 14,000 km across the length and breadth of a roadless country, analysing rock outcrops and mapping the orogenics. But the more he studied Nepal, the more Toni Hagen found his interest veering away from rocks to people. He was looking for mineral treasures that would turn Nepal into a modern developed nation, but he found treasure of a different kind: the Nepalis\' capacity for hard work, their fortitude and cheerfulness. As he got to know them up close and personal, Toni Hagen became a lifelong admirer of the Nepali people.

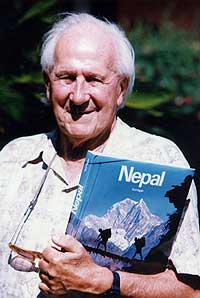

Toni Hagen died on Friday at his home in Lucerne at age 86, one day before he was to fly to Nepal to attend a conference which on 25 April will premier the film Uhileko Nepal containing the 8mm visuals he shot 40 years ago. The screening will start a conference by the Social Science Baha on the theme, The Agenda of Transformation: Inclusion in Nepali Democracy. The subject matter itself is a fitting tribute to a man who never abandoned his belief that this diverse land can only be governed and developed by decentralised planning and grassroots participation through democracy.

Toni Hagen was a die-hard optimist about Nepal. Many Nepalis are fashionably cynical about their own country, but he was always spreading hope. On a visit in 2000 during the dark days of the insurgency, he predicted that Nepal could come out of the crisis stronger as a nation. When asked why, he replied, "Because I see the younger generation of Nepalis value their freedom, and want to change things."

In the past 50 years, Toni Hagen had unsurpassed access to Nepal's rulers. He knew Mohan Shumshere in 1950 to King Mahendra, BP Koirala, Ganesh Man Singh. In 1981, Toni Hagen met King Birendra in Switzerland and they had a long conversation about development. Finally, King Birendra asked him: "Is it too late for Nepal?" Toni Hagen recalled replying: "No. It's late, but it's never too late."

With his characteristic bluntness, Toni Hagen pushed his conviction that Nepal needed an alternative formula for development. That is why he opposed the Arun III ten years ago in favour of smaller decentralised units. Nepal's present success story with indigenous suspension bridge building was based on his early efforts to help farmers increase income with access to markets. He was a strong advocate for multi-modal transportation with cable cars and cargo-ropeways for the mountains, and thought reliance on motorised transport and highways would be expensive to build and maintain.

Toni Hagen wasn't a utopian Luddite. But he believed in taking one step at a time, mastering one level of technology before moving on to the next. Some of the hydropower projects he first studied (Kulekhani, Kali Gandaki) have now been built. But the cautionary notes he made after studying the possibility of a high dam on the Karnali at Chisapani in the early 1960s are as prescient today as they were then.

Toni Hagen has left us a strong and clear legacy. What he told King Birendra in 1984 when he was awarded the Birendra Alankar Medal for national service was what he told everyone ever since: Nepal needs to be self-sufficient by using local expertise, local financing and technology appropriate for our level of development. "But all this has to start at the grassroots," he told us three years ago. "The people have to participate in shaping their own destiny. No one can dictate to them, and you cannot have democracy through violence and bloodshed."