But the mountains have also come to be associated with pseudo-nationalism, personal ego, glory and money. The Nepali people would benefit from more and smaller flexible, club-type climbing of the lesser peaks. The 50th anniversary of the first ascent of Sagarmatha may be a good time to go back to the basics of the aesthetics of climbing where you can do more with less. Kanak Mani Dixit (pic, right), the editor of Himal South Asian magazine talked to noted British alpinist-turned-anthropologist, Michael Thompson (pic, left), about climbing ethics, nationalism, mountaineering and the market. Excerpts from the conversation:

Kanak Mani Dixit: It's been 50 years since Tenzing and Hillary got to the top of Everest. Tenzing was a Himalayan and a climber at heart. If you read his writings, even those translated autobiographies, he was somebody with that fire in the belly of a climber, the sensibility, the broad-based understanding of the whole idea of climbing. It's been 50 years, but we are still looking for climbers like him in the Himalaya. There are few climbers in Nepal that come out of the urban milieu. I can't say whether this is a plus or a minus, but we haven't evolved mountaineering as a sport in Nepal.

Kanak Mani Dixit: It's been 50 years since Tenzing and Hillary got to the top of Everest. Tenzing was a Himalayan and a climber at heart. If you read his writings, even those translated autobiographies, he was somebody with that fire in the belly of a climber, the sensibility, the broad-based understanding of the whole idea of climbing. It's been 50 years, but we are still looking for climbers like him in the Himalaya. There are few climbers in Nepal that come out of the urban milieu. I can't say whether this is a plus or a minus, but we haven't evolved mountaineering as a sport in Nepal.

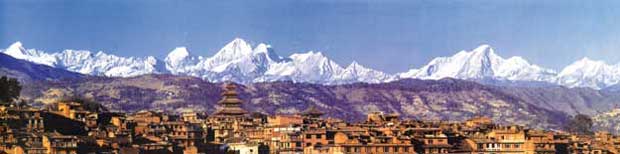

Michael Thompson: If you look at how it happened in other mountaineering countries, there is a strong base of climbing. People start with hiking and then rock climbing and can even join numerous climbing clubs. That's how I started. You do some basic climbing at home and go for your first trip to the Alps. One thing leads to another and then you say, "Hey! We can go to the Himalaya." So you need to have this base and Kathmandu, with so many peaks of great variety nearby, could emerge as one.

KMD:But we haven't even reached the stage, people haven't even started hiking to the ridges along the Valley rim.

MT:Well, it will happen when people start saying, "Wow! What a fantastic country we've got." And it's a kind of middle class thing as well.

KMD:Clearly, we have a middle class but our middle class doesn't even climb Phulchoki, Nagarjun or Chandragiri.

MT:That will come. I think it's got to come. People will get bored. Young people with a bit of money will get bored if they are just going around on motorbikes. And you've got a fantastic country full of beautiful mountains. It will happen.

KMD:Then would people have to get more bored before they become more interested in hiking and climbing?

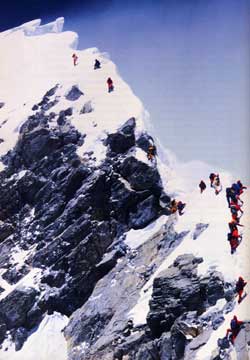

MT:Perhaps, and there might be something impeding it which is the official Nepali attitude to Himalayan climbing. What I know of the 50th anniversary is that the celebration is being presented in an absence of the aesthetics of mountaineering. They are proposing to give all the people who have been to the summit free visas as if getting to the summit was a uniformly worthy achievement. Or drawing up lists of summiteers and how many times they got there and so on.  The essence of climbing is always doing more with less. So for the first time 50 years ago, the thing was to climb the mountain. It was a big expedition. They had oxygen and everything. The technology, knowledge, techniques and equipment were a lot different from today and they really pushed themselves to what was unknown and they got up there. That was a terrific achievement. Then, later people tried to do more difficult routes with the same-sized expeditions on the west-ridge climb.

The essence of climbing is always doing more with less. So for the first time 50 years ago, the thing was to climb the mountain. It was a big expedition. They had oxygen and everything. The technology, knowledge, techniques and equipment were a lot different from today and they really pushed themselves to what was unknown and they got up there. That was a terrific achievement. Then, later people tried to do more difficult routes with the same-sized expeditions on the west-ridge climb.

KMD:Then there is the fact that we've let our nationalism run away with our mountaineering. It started right off the bat when Hillary and Tenzing came off the mountain and it was all murky-who was Tenzing? Was he Tibetan? Was he Nepali? And in the process, of course, the Nepali state took him over. We lionised him, but the moment he decided to go back to Darjeeling we just dropped him like a stone. We still haven't appreciated Tenzing as a climber, our nationalism took over. When Tenzing chose to live in India he suddenly became persona-non-grata to us. He is a true Everest man. He's seen the east of Everest, since he was born there, he's worked in the west of Everest, he tried Everest from the north and then actually achieved the summit with Hillary from the south in 1953. There isn't anyone more Himalayan than Tenzing, yet he did not fit our definition of Nepali nationalism. Likewise, we regard our mountains as if they were proof of our achievement. Tectonic factors made them high, not our hard work. Nepali children and adults and even our political leadership exhibit pride that Sagarmatha is ours forgetting that only half of the mountain is in Nepal. Nationalism has overwritten nature and mountaineering. And proof of that is the lack of genuine empathy and understanding among our public of the Everest 50th anniversary. But all is not lost. Hopefully, we can use the celebrations to inform the Nepali public about what these mountains mean to us.

MT:If somebody asked me what I think should be done with the 50th anniversary, I'd say just look at all these big expeditions to Everest. They are pulling the mountain down to their ability, they are dragging it down instead of climbing it. Everest has become a terrific honeypot. Well, one idea that crossed my mind, though it is a rather extreme measure, is to really try enforcing the aesthetics. I'd say don't allow any expedition on Everest where they've got more than one member. And don't allow any oxygen. That would stop that oxygen shop. You can have oxygen down below at the Himalayan Rescue Association for medical purposes.

KMD:Or maybe a moratorium until the mountain is clean, or to have a limitation on the number of teams. But can you enforce adventure on people? Isn't it like saying "Okay, I hereby decree only the adventurous shall climb Everest".

MT:It's not so much enforcing adventure on people, but taking away the non-adventurous. It is an extreme measure but it's well worth thinking over. The other thing is mobile and satellite phones. You call up and say I'm stuck. That sort of destroys things. In the best and the most congenial restaurants and clubs in say, London, you'd have to leave your mobile phone in a basket. In the wild west you had to put your gun away before you went into a saloon. Well, maybe we could do something like that or make expeditions walk all the way either going or returning, right from Kathmandu

KMD:Or Jiri. A proactive way in which the local economy benefits, and at the same time sees the aesthetics are restored to some extent.

MT:I don't mean to say that people who are not of the highest calibre can't go climbing. But they'd start to say, okay, what can I do? What is within my ability? The smaller mountains for instance. And there are of course a lot of small mountains. So then you get away with much more exploratory climbing. Not desperately hard, but exciting. Another thing is not actually the mountains but crossing the passes, which seems as exciting as climbing the mountains.

KMD:Because of all the climbing you and others have done, the Himalaya is seen as a place for extreme climbing and for extreme heroics. People tend to forget that there are hundreds of smaller peaks besides the eight-thousanders. It also seems to me climbers are coming, but the demand is for these high-end, exotic, guided-climbs of Everest.

MT:Partly it is because Nepal has not being able to market itself, and partly it is the function of the market not having developed itself in the West to come and holiday or club climb in Nepal. Maybe there are so many things to do in the world of adventure that mountaineering gets proportionately fewer people excited: you can go scuba diving, rafting, caving and hand gliding. I think the world of adventure has expanded and climbing is not catching up commensurately with the rest of adventure sports.

Mountaineering is not just climbing up the mountains. You have to appreciate the landscape, the people, how the farming system affects livelihoods, the wildlife, the ecology and the birds. So instead of jumping on a plane and getting off at Lukla, if you walk all the way there and eat dal-bhat in little places along the way, you are getting much, much more.

KMD:What Nepal could do is challenge the spirit of adventure. The world of adventure has shrunk because everything is packaged and people are not reaching out. Nepal is meant for people who can do that. We may have the highest mountains but we also are the most-populated mountain region in the world, which gives us tremendous diversity, not to mention bio-diversity. Where else on earth do you have a country like this?

MT:Oh, you're right, nowhere. When tourism picks up again in Nepal, the opportunity exists to do niche tourism. People can come up here for an amazing range of activities.

KMD:We could use the 50th anniversary for this refocusing as well as to remind the world that there is a ceasefire, and Nepal is safe. It is also important because climbing and trekking employs large numbers of porters not just in the trekking areas but also in non-tourist areas. There used to be significant cash income for hill villagers. In the last 3-4 years that has been blocked off. The Maoists never deliberately targetted tourists, which was our saving grace. Nevertheless, the world still thinks there is a Maoist thing raging in Nepal-even after the ceasefire. So we could use, perhaps cynically, the 50th anniversary event to tell the world to come here and have a look.

MT:One thing different about Nepal from a lot of poor countries is a tremendous amount of people out there in the world who have spent their formative years in this country. Members of the Peace Corps, climbers and all sorts of people care very much about what happens to Nepal. They worry about Nepal and would like to know things are normal over here. Mind you, many of these people are in very influential positions.

There is a huge audience of well-wishers out there and, yes, it would be worthwhile sending across that message.