Homraj Acharya's native village in Kapilbastu district is called Buddhi. Although the word means "intellect" in Nepali, there wasn't much for the children of Buddhi to read. Children would go to school to learn to read and write, but after graduation there was really nothing for them to read and no reason to write. Many lapsed back into illiteracy. Today, Homraj Acharya is working on his PhD at the American University in Washington DC, and he decided to do something about it by starting a unique project called "Books in Every Home".

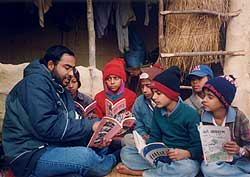

Homraj Acharya's native village in Kapilbastu district is called Buddhi. Although the word means "intellect" in Nepali, there wasn't much for the children of Buddhi to read. Children would go to school to learn to read and write, but after graduation there was really nothing for them to read and no reason to write. Many lapsed back into illiteracy. Today, Homraj Acharya is working on his PhD at the American University in Washington DC, and he decided to do something about it by starting a unique project called "Books in Every Home". Homraj (with children in his native village, below) uses his own savings and money from fund-raising dinners at Nepali restaurants to support a pilot scheme to provide reading materials to schools back in Kapilbastu. The experiment has proved so successful that he now wants to expand its reach to five other districts. "It is important to show that if you want to make a difference, you have to be ready to put in your own resources and energy," Homraj told us while passing through Kathmandu on his way to Kapilbastu with another load of books.

The problem is that the project has become so successful that Books in Every Home now needs more funds to expand. Which probably means more fund-raising dinners in various Nepali restaurants in the DC area. Homraj has already cancelled his own cable TV subscription and isn't ordering anymore takeout pizzas so he can stash the saved-up money into his book fund. "It may not sound like much, but it adds up and you can do a lot with little in Nepal," he says.

How do you make people love books, get hooked to reading so they can unwrap the knowledge in them? Books in Every Home tries to bring books with appropriate information and relevant facts to villagers. The project publishes a quarterly booklet called Desh ko Abaj containing all kinds of information on everything from bee-keeping to short stories, poetry or chapters on the importance on safe drinking water. The material is written by readers themselves who want to share their ideas. The latest issue contains an article Man ko Biraha by a teashop owner, and his neighbours are impressed he can write so well. The books are distributed through schools, and readers range from boys and girls in grade five to 70-year-old grandmothers.

Besides Desh ko Abaj, the project also circulates books in a mobile village library system organised by readers' groups called Pathak Samuha. Members gather every fortnight to discuss what they liked, why and how they could apply some of the things they have read about in their daily lives. Some members take the books home to read to their children at bedtime.

Says Homraj, "We bring books to people rather than take people to books." And what could be a better place to spread enlightenment than in a village called Buddhi, in the district where the Buddha was born.