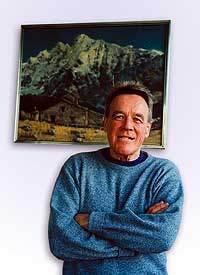

Three decades after taking part in an expedition that climbed the southwest face of Sagarmatha (and 50 years after the world's highest peak was climbed for the first time) Michael Thompson still glows with a sense of achievement.

Three decades after taking part in an expedition that climbed the southwest face of Sagarmatha (and 50 years after the world's highest peak was climbed for the first time) Michael Thompson still glows with a sense of achievement. "Everest had been climbed many times up the South Col, but our expedition went straight up from the Western Cwm, at that time it was considered the last great problem in mountaineering," recalls Michael.

Apparently, Reinhold Messner thought so too. When the two finally met at a mountaineering meet two years ago, Messner acknowledged that he was also preparing to climb the southwest face, and when the British upstaged him he wanted to do something even more daring, and went on to become the first person to climb Sagarmatha solo and without bottled oxygen.

Michael is a soldier-turned-mountaineer-turned-anthropologist, and was in Kathmandu recently to speak on his favourite subject-culture theory, a research tool used to interpret human behaviour in hierarchies and groups and applied to analyse the failures of everything from mountaineering expeditions to governments.

Michael's interest in Nepal and the Himalaya grew after he served with Gurkha soldiers during the counter-insurgency Malaya campaign in the late 1950's. He was in the 1970 Chris Bonnington expedition to the south face of Annapurna, one of the tallest vertical mountain walls on earth. Coming off the mountain, and on an easy stretch, Michael and his friend Ian Clough were caught in an ice avalanche. Clough was killed and Micahel survived miraculously. On the Everest southwest face expedition, another friend, Mick Burke, died on the way down from the summit.

"On average there was one death on every Bonnington expedition. And with 6 or 7 people on an expedition, the odds were not looking good," Michael told us. So he quit hard climbing and began studying the anthropology of expeditions, their organisation and financial aspects, looking at things like "risk perception". Of the numerous Sherpa climbers he interviewed, many got hooked and continued climbing. "A few Sherpas quit and went back to farming," Michael says. "They're not very rich, but they're quite content."

A bit like Michael himself, who now teaches at Norway's Bergen University where he is involved in research into technology and democracy. "This is a critical subject for countries like Nepal," he adds, "you have to make technological decisions, for example about high dams or fossil fuels, with huge potential impact."