They come across the border by the thousands every day. Young, old, men and women fleeing the fighting in Nepal for safety and jobs in India. It is happening in most towns along Nepal's 1,800 km frontier with India, but the exodus is most visible here on the Indian side of the border from Nepalganj.

They come across the border by the thousands every day. Young, old, men and women fleeing the fighting in Nepal for safety and jobs in India. It is happening in most towns along Nepal's 1,800 km frontier with India, but the exodus is most visible here on the Indian side of the border from Nepalganj.

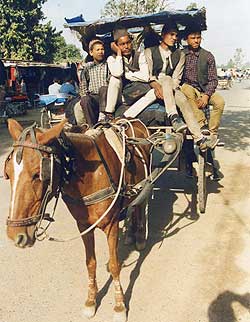

They emerge from under Nepal's welcome arch at the border, and head straight for the bus park or the railway station in Rupediya (see picture, above). From here they will travel to cities across India to friends and relatives.

This is not new, Nepali hill farmers have been migrating for decades after their harvests to find seasonal work in India. But what is different this year is the sheer volume of displaced people, and the fact that they are not seasonal migrants-many are not going to return until Nepal returns to normal. It is obvious that added up, there

is a massive humanitarian crisis brewing here.

The outflow of villagers from insurgency-hit mid-western districts has now reached a peak. Officials at the border police post at Nepalganj told us they counted more than 8,000 people passed through during the week 4-11 December, the highest weekly figure that they have ever recorded.

Those leaving Nepal range from three-month old children in the lap of mothers to 60-year-old villagers. Clad in torn jackets, dirty caps, slippers and jute sacks full of belongings, they have been travelling on foot and bus for days to reach this border. But here, their ordeal has just begun as they face an uncertain future in a foreign land.

"We left because it was getting more and more dangerous. The soldiers come and want to know about Maoists, and the Maoists come and punish us for talking to soldiers," says Tanka Shahi, 24, who has left his home village of Jamla in Jajarkot and is headed to India. He doesn't know where he is going, or what type of work he will get. All he knows is that he wants to be somewhere safe.

"We left because it was getting more and more dangerous. The soldiers come and want to know about Maoists, and the Maoists come and punish us for talking to soldiers," says Tanka Shahi, 24, who has left his home village of Jamla in Jajarkot and is headed to India. He doesn't know where he is going, or what type of work he will get. All he knows is that he wants to be somewhere safe.

Tanka is an SLC graduate, and used to farm his family's terraces. This year, the situation deteriorated after the army launched an operation, and he left even without harvesting the winter crop. He thinks the harvest would have been looted by the Maoists anyway, so there was no point staying.

Many of the Nepalis end up as apple pickers in Simla, where they have friends. Others find work as construction crew, kitchen help in restaurants, or even rickshaw-pullers in cities of north India. "In India they can not just earn some money, but they will also have security," explains Niraj Acharya, former member of the Jajarkot district development committee who has himself fled for the relative safety of Nepalganj.

Those leaving their villages need letters from the authorities to prove to Nepali and Indian police that they are not Maoists. But since most VDCs and police posts don't exist, refugees have to travel to the district headquarters of Dailekh, Jajarkot, Rukum, Rolpa and Surkhet to queue up for their papers.

Those leaving their villages need letters from the authorities to prove to Nepali and Indian police that they are not Maoists. But since most VDCs and police posts don't exist, refugees have to travel to the district headquarters of Dailekh, Jajarkot, Rukum, Rolpa and Surkhet to queue up for their papers.

Tilak Oli is a labour broker in Nepalganj who tries to connect Nepali workers with Indian employers. Indian contractors hired a group of 66 of his workers who said they had to pay a bribe of Rs 1,800 to the local authorities at Chhinchu VDC in Surkhet district. When contacted, VDC secretary of Chhinchu, Guman Singh Neupane, said his office did not charge any fees for issuing clearance papers. Our investigation showed that lower level staff at the local police post had indeed raised money from the 66 villagers to provide them the letter of safe passage. Incidents like this make many villagers glad to be leaving a land where there is no justice anymore, and where they are exploited by both the government and the rebels.

Paradoxically, the unfolding human tragedy of the mid-western districts has resulted in an urban boom in Nepalganj. Roadside lodges and restaurants are doing a roaring business, and transport operators in Nepal and India have a lot of customers. Wealthier people from the northern districts have moved permanently here, buying property and building houses on the outskirts of Nepalganj.

Satta Prakash Singh, who operates a private bus service in India out of Rupediya, told us: "I have had to double my fleet to accommodate the Nepalis." Singh's company used to operate eight buses from Rupediya to Delhi, Hardwar and Simla daily till a few months ago. "Now, we operate a total of 20 buses every day," he said. Ten three-wheelers used to ferry passengers from Nepalganj to Rupediya till last year, now there are over 25.

Satta Prakash Singh, who operates a private bus service in India out of Rupediya, told us: "I have had to double my fleet to accommodate the Nepalis." Singh's company used to operate eight buses from Rupediya to Delhi, Hardwar and Simla daily till a few months ago. "Now, we operate a total of 20 buses every day," he said. Ten three-wheelers used to ferry passengers from Nepalganj to Rupediya till last year, now there are over 25.

Go to Rupediya on any given day, and you can see hundreds of Nepalis boarding buses here. One bus we saw this week with a capacity of 70 passengers was carrying 100-all of them Nepalis bound for Lucknow. As Nepali nationals do not need a passport or visa to travel to India and it is much cheaper to travel by land route across the border, India is the destination of choice. As long as the insurgency continues, it is clear that this migration will not stop, and perhaps it will even intensify.  The question is: can the Nepali hills sustain losing 16,000 mostly-able bodied men every month? Who will plant crops, maintain terraces, take care of the families who remain behind?

The question is: can the Nepali hills sustain losing 16,000 mostly-able bodied men every month? Who will plant crops, maintain terraces, take care of the families who remain behind?

This humanitarian crisis also highlights the trans-boundary nature of the conflict in Nepal. So far, there have not been any reports of Nepalis being prevented from entering India, but officials here say that with the tight job market in India which is already full of its own internally displaced people and the possibility of more Nepali migrants moving down, the situation needs to be carefully monitored by both governments.