They say the Grand Hyatt in Mussoorie is a "7-star" hotel. It is plush enough for a conference on mountain farming systems. Having slid through the polished lounge, past plastic palm trees giving a virtual desert ambience, muted lights, and sinking into a bed no less bouncier than an Olympic trampoline, I feel a tinge of guilt and worry.

They say the Grand Hyatt in Mussoorie is a "7-star" hotel. It is plush enough for a conference on mountain farming systems. Having slid through the polished lounge, past plastic palm trees giving a virtual desert ambience, muted lights, and sinking into a bed no less bouncier than an Olympic trampoline, I feel a tinge of guilt and worry. Many Nepalis seem willing to have US military help to wage war, what happened to our self-reliance, our sincerity and integrity, our trademark generosity of spirit? Where are the development pundits? Where are the gender experts analysing the desperately more desperate situation of Nepali women, now caught in conflict?

I stand on the podium and look at the sea of faces: government officials, scientists, researchers, development workers, diplomats.

We are here to discuss marginal farmers. I feel dizzy with the sheer enormity of the challenge. The sterile developmentese suddenly sounds irrelevant. I sound like the mad monk, as I talk of conflict that pushes the marginalised even more to the periphery.

We know the definitions, of course: someone or something on the periphery, someone debarred from receiving benefits commensurate to their status. In the case of land, we could simply understand it as "not fertile enough for profitable farming".

Aspects of marginality in mountain areas are marked by poor inaccessibility, degraded environments and exploitation of natural resources such as forests, population growth and fragile mountain eco-systems. Within all this, the women are "doubly marginalised" by social discrimination and increasing workload.

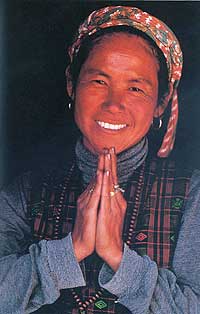

Today, they are "triple marginalised" by a conflict that is making life of a mountain woman in Nepal even more difficult. Besides the increased hardships and lack of food, there is bereavement, families torn asunder and migration isolating her and forcing her to fend for herself. From only "worrying about" providing for her family, she has now become sole provider. She is not just a contributor of labour to mountain farming systems, she is the only one left to take care of the young and the elderly.

Impacted male migration has cleared the villages of able-bodied men. Male migration left women to manage the best they could, but the hope remained that the household family income would be supported by remittances. Today, men are migrating to get away from forced recruitment by the insurgents, or to escape the security forces. They haven't migrated for jobs, they have run for their lives. Women are forced to take over the men's chores as well: ploughing fields, maintaining irrigation canals, protecting community forests, and selling produce.

And the conflict restricts development aid that was targeted at making womens' lives better: capacity building, empowerment, micro- credit and, as last resort, food for work. Mother Nepal is struggling as she always has against overwhelming odds, not expecting any help.