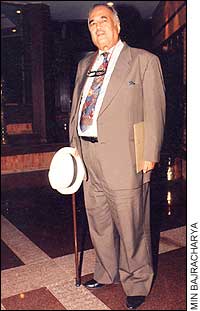

There is something particularly winsome about an ailing old man lighting up and giving you a smile of welcome. That is how Rishikesh Shaha greets you when you enter his room. After the initial shock of seeing how wasted he looks, the first thing that strikes you is the dhaka topi that somehow remains perched on his head even in repose. Then the sadness creeps over you as you realise that there lies a piece of Nepali history, and he is dying of lung cancer.

There is something particularly winsome about an ailing old man lighting up and giving you a smile of welcome. That is how Rishikesh Shaha greets you when you enter his room. After the initial shock of seeing how wasted he looks, the first thing that strikes you is the dhaka topi that somehow remains perched on his head even in repose. Then the sadness creeps over you as you realise that there lies a piece of Nepali history, and he is dying of lung cancer. While working with Himal South Asian, we used to describe Rishikesh Shaha as Nepal's scholar-statesman, and I doubt if there is any other Nepali who can share that designation. Just look at his accomplishments. A founding member of the Nepal Democratic Congress, one of the constituents which later became the Nepali Congress, he later sided with Dilli Raman Regmi in the Nepali National Congress, and was even part of the People's Front together with Tanka Prasad Acharya's Praja Parishad and the Communist Party of Nepal to oppose Nepali Congress policies.

Thereafter, he left for New York to set up Nepal's permanent mission to New York in 1956, and also served as the country's first ambassador to the US. It is a measure of his stature in the world body that in 1961, he was appointed chairman of the international commission to investigate the death of Dag Hammarskj?ld, the UN secretary-general who died in a plane crash in the Congo.

Shaha was brought back to Nepal in 1960 after King Mahendra's takeover to serve as a cabinet minister. For the next couple of years, he was shunted around as Foreign Minister, special ambassador to the UN and as chairman of the commission to draft the Panchayat constitution. Having won a Rastriya Panchayat seat from the graduates' constituency in 1967, his statement calling for a more representative and a more responsible political system landed him a 14-month prison sentence.

Shaha never served in a public post after that, but became prolific as a scholar. He was a visiting professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University and Regent's Professor at the University of Calfornia at Berkeley. His books, most notably, Nepali Politics: Retrospect and Prospect, Essays in the Practice of Government in Nepal and Modern Nepal: A Political History have become standard reference works, while his Introduction to Nepal and Heroes and Builders of Nepal provide perhaps the best introduction to the country.

Rishikesh Shaha's deep commitment to the issue of personal freedom was evident when he founded and led the Human Rights Organisation of Nepal in 1988; no mean feat during the authoritarian Panchayat days. He later left the organisation but did not relent in his own personal crusade against injustice.

In recent years, Shaha was accused of being an apologist for the Maoists because of his friendship with Baburam Bhattarai, with whom he corresponded even after Bhattarai went underground. But Shaha was also accused of being pro-absolute monarchy for asking the king to step since he believed the politicians were ruining the country.

But he was above all a humanist, and a keen analyst of the Nepal's political evolution. Writing in 1996, a couple of months after the "people's war" began, Shaha said: "The signs of an imminent legitimacy crisis are already visible in Nepal's fledgling democracy, and the immateriality accorded to the civilian deaths in Rolpa is a foretaste of difficult days ahead." Only a statesman with vision can foresee events so far into the future.