Propelled by the rumours of an impending settlement between Maoist rebels and the palace, the trial balloon of a constituent assembly is once again up in the air. But will such an assembly create more problems, rather than solving our existing ones, remains to be answered satisfactorily.

Propelled by the rumours of an impending settlement between Maoist rebels and the palace, the trial balloon of a constituent assembly is once again up in the air. But will such an assembly create more problems, rather than solving our existing ones, remains to be answered satisfactorily. Controversy over the constituent assembly dates back to 1951, when King Tribhuvan proclaimed: "It being our desire and decision that our people, henceforth, be governed by a democratic constitution framed by the Constituent Assembly, elected by them...". The royal "desire and decision", however, never got implemented.

After a decade of uncertainty, political parties accepted King Mahendra's proposal to go directly for parliamentary polls.

After a decade of uncertainty, political parties accepted King Mahendra's proposal to go directly for parliamentary polls. Perhaps King Mahendra had expected that a hung parliament would give him some room for political manoeuvring. The electorate, as is its wont, threw cold water over the ambitions of the king. Voters sprang a surprise and gave the Nepali Congress a two-thirds majority. In effect, this meant that the new parliament was almost a constituent assembly-it could amend all the provisions of the constitution save its fundamental principles. Alarmed by that possibility, King Mahendra dismissed parliament and put the first elected prime minister of the country in jail within 18 months of the general elections and reneged on the solemn promise made by his father.

The demand for an elected constituent assembly remained dormant all through the years of struggle for restoration of democracy. When BP Koirala came back from political exile announcing that he and the king were "joined at the neck", the constitutional monarchy became an article of faith with the Nepali Congress.

Some fringe groups on the left, particularly the Nepal Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) then running a violent campaign in Jhapa, did espouse the dictatorship of the proletariat, but most mainstream political forces had their problems with absolute monarchy, not with the monarchy as such. After the referendum verdict, BP Koirala told Bhola Chatterji of Calcutta's Sunday magazine in 1979 that the Nepali Congress was not for monarchy, but "kingship". Kingship, according to Hindu scriptures, is power held by a ruler in trust-on behalf of the ruled, and with their consent. Such a concept has no place for absolute monarchy or executive kings.

Perhaps King Gyanendra alluded to this distinction when he told me earlier this year that the constitution of the kingdom of Nepal 1990 was a document of compromise between three political forces of the country-democrats represented by the Nepali Congress, communists represented by the Left Front, and the rest of the people represented by the king. There is only one problem with this interpretation of the People's Movement of 1990: how do we know whether the rest of us want the king to be our representative? The answer, as many self-professed acolytes of BP Koirala have begun to propose after 4 October, may lie in the formation of a constituent assembly empowered to debate the future of monarchy itself.

However, in a country in the violent grips of insurgency and counter-insurgency, the idea of a constituent assembly has its own pitfalls. First, free and fair polls aren't possible when armed insurgents terrorise the countryside with impunity. Second, there is nothing to stop an engineered assembly from initiating a process of republicanism eventually leading to Sikkimisation. The political elite in Kathmandu Valley may not be aware of it, but people in the countryside have already started debating whether the fate of a protectorate like Bhutan can be any worse than prolonged violence and insurgency. The third risk is that of conservatives holding sway in an unfair election leading to the curtailment of existing rights. Then there is the ever-present question: will the promise to hold elections for the constituent assembly once again become an excuse to keep the country in a political limbo?

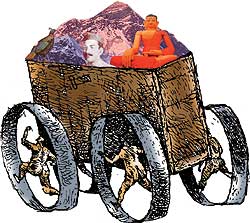

By declaring that the state authority is inherent in the king rather than the people, King Gyanendra has virtually brought out the square wheel from the Narayanhiti attic. But that should not give an excuse to a galaxy of constitutional experts and political scientists like Bishwanath Upadhayay, Daman Nath Dhungana, Narhari Acharya, Lok Raj Baral, Krishna Khanal and Krishna Hathechhu to get engaged in the pointless task of reinventing the circular wheel.

What is perhaps needed more urgently is a sincere attempt to bring the four-wheeled vehicle of the democratic train back on track. We all know what those wheels are: legislative assembly constituted by adult franchise, an executive body formed by multiparty elections, an independent judiciary to ensure rule of law, and a constitutional monarchy as a symbol of unity of all Nepalis.

Given the history of animosity between democratic forces and the king, the restlessness among the rank and file of the Nepali Congress is perhaps understandable. But a confrontation between the two at this juncture is the last thing that we need. In any case, it was Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba who badly wounded the constitution by his midnight recommendation for the dissolution of parliament. All political parties then took their turn to rub salt over the wound. Under the circumstances, the worst thing that King Gyanendra can be blamed for is mercy killing the constitution.

It is incumbent upon all stakeholders of democracy to ensure the re-birth of the constitution without being entangled in the never-ending debate over a constituent assembly. Everything a constituent assembly can do, a sovereign parliament can do better, and at less cost to society. For a country already in violent convulsion, debating the future of kingship is hardly an issue of priority. Restoration of the democratic process is much more urgently needed, to face the twin challenges of a leftist insurgency and a rightist resurgence.