"When the devotees and people of the country are deprived of their gods and goddesses, their hearts bleed. The stealing of such religious images is an atrocity, a serious crime... Let us hope that some day these stolen sculptures will be returned to their respective temples and shrines." - Lain Singh Bangdel in the conclusion to Stolen Images of Nepal.

"When the devotees and people of the country are deprived of their gods and goddesses, their hearts bleed. The stealing of such religious images is an atrocity, a serious crime... Let us hope that some day these stolen sculptures will be returned to their respective temples and shrines." - Lain Singh Bangdel in the conclusion to Stolen Images of Nepal.

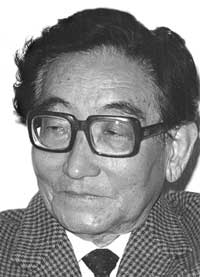

While Nepali society knows Lain Singh Bangdel as an artist, and while scholars laud his contributions to Nepali art history, one of his lasting legacies will be his call to arms against the scourge of idol theft. Born in Darjeeling in 1924 and arriving in Nepal in the early 1950s after studying art in Paris and London, Bangdel was impressed by Kathmandu Valley's rich heritage of religious statuary, and published several scholarly volumes on the subject.

But even as he watched, the idols began to disappear. As art theft peaked in the mid-1980s, he began preparing his book Stolen Images of Nepal, which was published by the Royal Nepal Academy (of which he had earlier served as head) in 1989.

Bangdel's book provided photographic documentation, juxtaposing Before and After images of places that held statuary. He said, "I felt it was important to provide strong and authentic photographic evidence of sculptures which were stolen from the Valley and surrounding areas."

The dying years of the Panchayat were a dangerous time to be talking about idol theft, because it was happening rampantly with the suspected involvement of the highest and mightiest. Despite his stature as a scholar, artists and, head of the Academy, Bangdel was threatened with his life if he kept up his crusade. Some suspected Bangdel himself of criminal activity because of his camera-toting activities.

J?rgen Schick, a German art-connoisseur, the only person besides Bangdel who could be called an 'idol theft scholar', remembers how Bangdel had shown him consideration more than a decade ago. Schick, whose own book on the subject is The Gods are Leaving Nepal, had been harrassed by the authorities for his interest in the matter of stolen statuary, and it was only in Bangdel, he recalls, that he found understanding: "When I found Mr Bangdel at the Academy, at last I had the one Nepali who showed sensitivity to this subject. No one else."

The reason to publish incontrovertible photographic evidence of theft of idols is so the matter of criminal culpability is proven beyond doubt, so that even decades later statues that have been lifted can be returned under international law. Also, the very act of publishing brings down the market value of Kathmandu Valley statuary, which reduces chances of future thefts.

The proof of Bangdel's efforts was there for all to see (if anyone was noticing) in the return in August 1999 of four pieces of statuary (from Kathmandu, Patan, Pharping and Panauti) were restituted by a California art collector who was shown Bangdel's book showing the statues in their original sacred sites. In 2000, a statue was returned from Berlin based on evidence in Bangdel's book.

At that time, Bangdel should have been garlanded taken around the town in a chariot, for his singular act of commitment in bringing out Stolen Images of Nepal. But even if today we do not fully appreciate this commitment, we are sure to in  the days to come, because the photographic and scholarly record left behind by the late Lain Singh Bangdel will be used far into the future in bringing "the gods which have left the country", back home.

the days to come, because the photographic and scholarly record left behind by the late Lain Singh Bangdel will be used far into the future in bringing "the gods which have left the country", back home.

This Uma Maheswor statue returned to Nepal, to Patan Museum, 18 years after it was lifted.