Love them or hate them, but you can't ignore them. The legacy of Rana rule remains everywhere: from the imposing fa?ade of Singha Darbar, the presence of Ranas at the top echelons of modern Nepal's business, army and police, and the Rana family tree, which is interwoven with the present members of the Shah dynasty. All this makes for fascinating history that has been documented in research papers, academic treatises, a best-selling novel, a Nepali movie, and recent Rana nostalgia in architecture.

Love them or hate them, but you can't ignore them. The legacy of Rana rule remains everywhere: from the imposing fa?ade of Singha Darbar, the presence of Ranas at the top echelons of modern Nepal's business, army and police, and the Rana family tree, which is interwoven with the present members of the Shah dynasty. All this makes for fascinating history that has been documented in research papers, academic treatises, a best-selling novel, a Nepali movie, and recent Rana nostalgia in architecture.

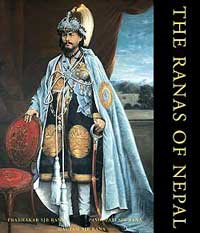

But surprisingly no one has, until now, attempted to put together a coffee table book on the history, culture, lifestyle and even cuisine of the Ranas-written by the Ranas themselves. Enter Princess Juni of the former Indian princely state of Sarela visiting Kathmandu two years ago for a Worldwide Fund for Nature conference. "She said how come there is no book on the Ranas," recalls Gautam Rana of Baber Mahal Revisted. Gautam already had a well-developed interest in his clan's heritage-when he returned to Nepal after completing a management degree in Germany in 1979, he was dismayed to see Kathmandu Valley rapidly losing what old charm it still had left. In 1998, he began reconstructing the stables and cowsheds of his ancestral palace to develop an upmarket shopping complex of boutiques, art galleries and restaurants called Baber Mahal Revisited.

Enter Princess Juni of the former Indian princely state of Sarela visiting Kathmandu two years ago for a Worldwide Fund for Nature conference. "She said how come there is no book on the Ranas," recalls Gautam Rana of Baber Mahal Revisted. Gautam already had a well-developed interest in his clan's heritage-when he returned to Nepal after completing a management degree in Germany in 1979, he was dismayed to see Kathmandu Valley rapidly losing what old charm it still had left. In 1998, he began reconstructing the stables and cowsheds of his ancestral palace to develop an upmarket shopping complex of boutiques, art galleries and restaurants called Baber Mahal Revisited.

"When she said that, I thought let's do it. But where was the money?" explains Gautam. A large-format, hard cover illustrated encyclopaedia of the Ranas was going to cost a packet. Luckily, in stepped the Swiss banking group Credit Suisse, which was interested in backing the project because the proceeds from the sales were going to help the conservation of Kathmandu Valley's unique urban heritage. With Credit Suisse bankrolling the printing in Europe, Gautam raised money from other illustrious Ranas who were going to be co-authors: Prabhakar Rana of the Soaltee Group and RPP politician, Pashupati Rana.

Balkrishna Sama's hypothetical painting of all nine Rana prime ministers.

"Pretty soon, I realised I may have bitten off more than I could chew," admits Gautam, who hired help for the editing, design and photography from India's APCA group, but was himself responsible for the research and coordinating the contents. The result is a well-crafted work that is like a time capsule taking readers back to the extravagance, intrigue, hopes and achievements of those 104 years.  The authors have tried not to gloss over the raw ambition, greed, and, yes, lust that drove the power struggles in the extended Rana clan. But the overall impression is still a somewhat sanitised retrospective of those years. Even the decadence comes across as photogenic. Gautam isn't defensive about that, he says: "Some Ranas of my generation feel very apologetic, but there is nothing to feel guilty about. We have an eclectic and cultured past, and that should inspire us to help build the country today, and conserve our heritage."

The authors have tried not to gloss over the raw ambition, greed, and, yes, lust that drove the power struggles in the extended Rana clan. But the overall impression is still a somewhat sanitised retrospective of those years. Even the decadence comes across as photogenic. Gautam isn't defensive about that, he says: "Some Ranas of my generation feel very apologetic, but there is nothing to feel guilty about. We have an eclectic and cultured past, and that should inspire us to help build the country today, and conserve our heritage."

Despite being an "inside story" by members of the clan vilified in post-1950 history books, the history chapters in The Ranas of Nepal are an objective and credible assessment of the period. Co-author Prabhakar Rana, great-grandson of Joodha Shumshere, actually lived in Singha Darbar until the age of 11. Pashupati Rana, grandson of the last Rana prime minister, Mohun Shumshere, was present as a boy of four at the first coronation of King Gyanendra in 1950. Both have contributed chapters on history, architecture, and lifestyle. Besides the research, Gautam helped track down rare photos, paintings and artefacts from private collections, and also wrote the chapter on Rana jewellery.

The book's lavish visuals with early sepia photographs, period portraits from private collections bring this history alive. The illustrations are intelligently grafted into the text (edited by Brinda Datta and Dubby Bhagat), as are the contemporary photographs by Indian photojournalist Prashant Panjiar.  The book begins at the beginning: with the royal rivalries among the Rajput rulers of Udaipur that drove one particular family of courtiers to the Himalaya, all the way up in Jumla. From there they migrated eastward to Kaski and on to Gorkha. The Kunwars helped King Prithvi Narayan in his conquests, and Bal Narsingh Kunwar was made governor of Jumla. But in the purges that followed the downfall of Bhimsen Thapa in 1840, Bal Narsingh's son Jung Bahadur emerged as a master manipulator who, through sheer charisma, craftiness and courage, wormed his way upwards taking full advantage of the savage power struggles among the descendants of Prithvi Narayan Shah and their consorts.

The book begins at the beginning: with the royal rivalries among the Rajput rulers of Udaipur that drove one particular family of courtiers to the Himalaya, all the way up in Jumla. From there they migrated eastward to Kaski and on to Gorkha. The Kunwars helped King Prithvi Narayan in his conquests, and Bal Narsingh Kunwar was made governor of Jumla. But in the purges that followed the downfall of Bhimsen Thapa in 1840, Bal Narsingh's son Jung Bahadur emerged as a master manipulator who, through sheer charisma, craftiness and courage, wormed his way upwards taking full advantage of the savage power struggles among the descendants of Prithvi Narayan Shah and their consorts.

Jung Bahadur is at the centre of this swirling tale of back-stabbing, intrigue, conspiracies, alliances, finding himself right in the middle of vicious infighting between a powerful queen and her paramour, the king, and the crown prince. At gunpoint, Jung is forced to shoot his own uncle, the prime minister, and is then caught up in two massacres at the Kot and at Bhandarkhal. He sends the queen and king into exile, installs the crown prince on the throne and makes himself prime minister.

Thus, at age 29, Jung Bahadur Kunwar launches the Rana century in 1845. He was also the first subcontinental royal to visit Britain and France, driven by a desire to bypass the obstructive diktats of Calcutta by dealing directly with London. Once there, he received royal treatment.  One gets the feeling reading these tales of massacres, assassinations and chronic infighting that contemporary Nepali rulers are just following in the footsteps of their ancestors-maybe they are hardwired to be divisive and selfish. A paragraph from the book, describing the conspiracies of the royal court could very well have been written about today's Nepal: "He (Jung Bahadur) brought order to a Nepal on the brink of anarchy. Nobody can condone the means he used to achieve this end. However, it begs the question: could it have been achieved by any other means?"

One gets the feeling reading these tales of massacres, assassinations and chronic infighting that contemporary Nepali rulers are just following in the footsteps of their ancestors-maybe they are hardwired to be divisive and selfish. A paragraph from the book, describing the conspiracies of the royal court could very well have been written about today's Nepal: "He (Jung Bahadur) brought order to a Nepal on the brink of anarchy. Nobody can condone the means he used to achieve this end. However, it begs the question: could it have been achieved by any other means?"

It was perhaps inevitable that when Jung died during a hunting trip in Chitwan in 1877, his brothers immediately started squabbling for power. Jung's brother, Dhir, installed Jung's brother Rana Udip Singh as successor, while he manoeuvred to take over. Suspecting a plot, he beheaded two dozen courtiers and managed to carve out a place for himself and his 17 sons in the succession. The clan was thus effectively split between the Jung Ranas and the Shumshere Ranas. By 1885, matters reached a head again and Dhir had his six sons kill their uncle, Rana Udip Singh and remove all the descendants of Jung Bahadur's other brothers from succession.

Rana power transitions were messy affairs, and watching all this from the background was the British regent at Lazimpat. We see how British India tried to influence events in Kathmandu, and this has familiar echoes today. When Bir Shumshere sidelined Jagat Jung and exiled him to India, the British refused for five months to recognise Bir as leader. And when Jagat Jung began preparations to overthrow Bir Shumshere from Indian soil, the British arrested him while he was planning to march into Nepal with his armed followers. Sound familiar?  Bir Shumshere built Nepal's first hospital as well as the Darbar School, for which imported teachers from England. He was succeeded by the flashy Dev Shumshere who in turn was replaced by the shrewd and astute Chandra Shumshere, whose 29-year reign was marked by uncharacteristic stability and development. He established Nepal's first college, streamlined administration, built suspension bridges all over the country, installed Nepal's first hydropower plant in 1911 (from domestic coffers, without foreign aid), and named the light powered by electricity generated by it after himself ("Chandra jyoti"). He sent architects to Europe and horticulturists to Japan for training. He also built a 1,400-room palace for himself, which ended up being a contribution to the nation-it is now Singha Darbar. On the diplomatic front, Chandra Shumshere managed to convince the British to officially agree to Nepal's independent status and got them to put it in writing in the 1923 Anglo-Nepal Treaty of Friendship.

Bir Shumshere built Nepal's first hospital as well as the Darbar School, for which imported teachers from England. He was succeeded by the flashy Dev Shumshere who in turn was replaced by the shrewd and astute Chandra Shumshere, whose 29-year reign was marked by uncharacteristic stability and development. He established Nepal's first college, streamlined administration, built suspension bridges all over the country, installed Nepal's first hydropower plant in 1911 (from domestic coffers, without foreign aid), and named the light powered by electricity generated by it after himself ("Chandra jyoti"). He sent architects to Europe and horticulturists to Japan for training. He also built a 1,400-room palace for himself, which ended up being a contribution to the nation-it is now Singha Darbar. On the diplomatic front, Chandra Shumshere managed to convince the British to officially agree to Nepal's independent status and got them to put it in writing in the 1923 Anglo-Nepal Treaty of Friendship.

Chandra was succeeded by Bhim Shumshere, Joodha Shumshere, Padma Shumshere and finally, Mohun Shumshere. But time was running out, the end of Empire was near. Although they tried to modernise Nepal with industrialisation, banking, railways, urban water supply, and even a liberal constitution, it was too little too late. Mohun Shumshere had to deal with newly-independent India and grapple with democracy-minded Nepalis whose demands sounded uncannily similar to today's discourse: set up a constituent assembly and form an interim government.

The book also delves into other massacres: that of tigers, rhinos and other wildlife in hunting expeditions in honour of visiting British royalty. There is a dramatic picture of Joodha Shumshere posing in front of pelts of a hundred or so tigers. Good thing many Ranas have now moved away from hunting towards nature conservation.

The rest of the book looks at Rana architecture, and mentions unsung Nepali engineers like Kishore Narsing and the legendary Joglal Sthapit, known more popularly as "Bhajuman". However incongruous the wedding cake Rana palaces may have looked when they were built, the authors argue that the palaces "seem to have achieved their own particular balance with the environment" with their use of local construction material and the incorporation of Nepali features such as courtyards, verandahs, and south-facing balconies.

The chapter on Rana jewellery traces the history of the Rana crown and how it evolved and bulged with gems and diamonds in 104 years (only to be sold to a Parisian jeweller in the mid 1950s). An error creeps in here-the bird of paradise plume is wrongly identified as coming from New Zealand; it is actually native to Papua New Guinea. Many of these gems, precious stones and ornaments were brought into Nepal by Indian royalty fleeing Mughal invasions. Other jewellery came from the Lucknow loot during the mutiny, of which the soldiers and officers got to keep the gold and silver while jewellery went to the royal coffers.

There's more: Rana cuisine, Rana lifestyle, Rana fashion, Rana art, and short biographies of some prominent living Ranas. The book also has a useful abridged family tree of most Ranas from Jung Bahadur's father to Siddhartha Rana, Prabhakar's son, so readers can navigate through the book's confusing genealogy, and untangle the complex web of Rana intermarriages with the Shah dynasty.

This hefty book with a hefty price tag will be available at Everest Book Shop, Baber Mahal Revisited from mid-November. Proceeds of the sales will go to the Kathmandu Valley Conservation Trust, which has renovated numerous temples, sattals and bahals in Kathmandu Valley.

The Ranas of Nepal by Prabhakar SJB Rana, Pashupati SJB Rana, Gautam SJB Rana. First edition Naef. Kister S.S. Editeur, Geneva, 2002. 262 pp.