After the problems with Nepali exports to India were fixed with the renewal of the 1996 trade treaty in March, everything looked set for a smooth flow of goods across the border. India wanted quantitative restrictions on some Nepali goods, Nepal agreed. Nepal wanted some inter-state taxes removed, and New Delhi got its state governments to comply.

After the problems with Nepali exports to India were fixed with the renewal of the 1996 trade treaty in March, everything looked set for a smooth flow of goods across the border. India wanted quantitative restrictions on some Nepali goods, Nepal agreed. Nepal wanted some inter-state taxes removed, and New Delhi got its state governments to comply. And yet, things remain stuck. Nepali exporters are amassing large inventories at warehouses because of bureaucratic hassles from the Bihar and Uttar Pradesh state governments, the need to pay off customs officials at the border, and the recent strike in Bihar. Many exporters now feel that exporting to India is just not worth the hassle, and are concentrating on building up a Nepali market for their products.

"The problems are procedural, even petty, but they have a big impact on our exports," says the manager of a vegetable ghiu manufacturer who has not exported a single consignment to India for the past two months. "Now we're thinking of selling only in the domestic market."

After the 1996 trade treaty, Nepal's export to India grew a whopping seven times in five years. But this boom is now all but over. Export growth last year was just 11 percent compared to about 80 percent two years ago. The statistics, however, do not reveal all because they do not portray the impact of the new export quotas on vegetable ghiu, copper wires, zinc oxide and acrylic yarn, among others. What is more worrying is that even exports of Indian multinationals manufacturing in Nepal have entered a downward spiral.

Until some years ago, every cake of Nepal Lever's Liril soap sold in India was made in Hetauda. And in the best years the Nepali subsidiaries of Indian multinationals were exporting Rs 2.26 billion worth of toothpaste. But last year, toothpaste exports to India slid to Rs 1.6 billion, and is plummeting further. Nepal's soap sales last year was roughly half the one billion two years ago (1999/00).

Companies like Lever have already switched gears to concentrate now on the Nepali market. But Colgate-Palmolive which came to Nepal mainly to export to India, is still in deep trouble. The Inter Governmental Committee (IGC) meeting in New Delhi last month agreed to review the problems affecting Nepali subsidiaries of multinationals but it may take months before the IGC meets again to make the adjustments.

The multinationals came to Nepal because they saw advantages of manufacturing here and selling to the vast north Indian market. But their profit margins were wiped out when the Indian budget slapped an excise tax based on the Manufacturers Retail Price, and not the price at which they transacted with their parent companies in India. Additionally, over time, India introduced other fiscal schemes to support its domestic producers, which have made manufacturing in India more attractive.

This is one of the issues the IGC in August agreed to look into, especially the adjustments needed to look into the difference the excise duty has made. "Indian fiscal policies and emergence of new tax-exempt zones in India have changed profitability," Gurdeep Singh, chairman of Nepal Lever Limited told us in Kathmandu last month. "I don't foresee major changes in our export in the near future."

It's not just the Indians. Nepal levies its own service charges on exports, and the multinationals have been complaining of messy taxation problems and delays in duty drawbacks. Then there are the complicated procedures involved in exporting to India, which dissuades all but the most determined Nepali manufacturers. Six months after renewal of the trade treaty, Nepali exporters still complain about rules and procedures in the Indian states bordering Nepal that seem to be designed to make it difficult for them.

"The treaty is fine, but the real hassles are with the day-to-day problems across the border," said the harassed ghiu exporter. Since May Ghiu exporters have to sell all their exports through India's state-run Central Warehousing Corporation (CWC) to which an Indian importer has to apply for an import license.

This license has to be used within 15 days, but because all ghiu sellers have to get every export batch tested and certified by a laboratory in Patna delays have become routine. Strikes in Bihar and the arbitrary hassles given by lab personnel to Nepali products stretch delays and disrupt delivery deadlines. Exporters complain that the Patna lab will reject a sample for being sub-standard, even though another from the same batch passed the tests.

Sometimes exporters are required to send samples from trucks at the border to Patna and wait for the reports to arrive before they can move on. The argument from the Indian side is that exports have to be tested because narcotics were discovered in some shipments in the past.

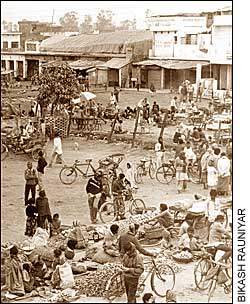

Kumud Dugar, an exporter of agricultural products, faces another problem and is pretty blunt about it: "Free trade ended the day we put restrictions on quantity. What is the point of being in business if you cannot expand volume and grow?" Dugar's main grouse is quarantine, which India began enforcing in August 2001 and has turned out to be a real hassle for exporters.

Dugar argues there is in effect no need to have quarantine checks because we have a porous, unrestricted border and same agro-climatic regimes and have been doing business in farm produce for ages. And the problems at the quarantine system seem to be geared for making the process as difficult as possible. Initially, there was only one checkpoint at Kakarvitta, and exporters in, say, Dhangadi had to truck goods 1000 km right across Nepal to get the certification. Two more checkpoints are operational now, but exporters told us that testing is done in Lucknow or Patna and they have to wait at the borders for reports to arrive back. The delays cause further losses of perishable agricultural exports.

Indian sources say the best they can do is simplify the quarantine system. India has promised to have three more quarantine checkpoints on the border by November. Now Nepal would have to formally tell India where the checkpoints should be located before the Indian bureaucracy will begin to budge, which has not happened. Informally, Nepal says it wants them near Janakpur, Sunwal and Jogbani, but has not officially requested it.

India has agreed to reduce quarantine fees by half but again that will take time and until then exporters have to live with what is in place. Some business sources argue that because Nepal also imports agro-products from India, and is also trying to join the WTO, it should also begin thinking about its own quarantine checks. But even that may not solve the problems exporters would face in India and further may add to the cost of the imports, which will then affect Nepali consumers.

In the end, traders and government officials say, it comes down to making sure that political decisions to streamline trade trickle down to the border posts and the quarantine centres. Says Dugar: "Our best bet is to try and focus on agro-products and processing. Only that can help us over the long run." This is because agricultural exports would have 100 percent local content and would be immune to pressure from India's domestic lobbies to protect trade, and also some of the new non-tariff barriers that have resulted from the treaty

renewal.