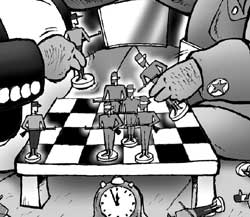

The murkiest member of the Maoist triumvirate has cast new light on the precariousness of our existence between two boulders. Comrade Badal has gained political prominence ever since Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba suggested he might have to open peace talks directly with the man responsible for the insurgents' battlefield ferocity. The rebel commander's characterisation of Nepal as dynamite between the two Asian giants was evidently intended to illuminate the firepower his lads and lasses still have. His broader point merits deeper introspection.

The murkiest member of the Maoist triumvirate has cast new light on the precariousness of our existence between two boulders. Comrade Badal has gained political prominence ever since Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba suggested he might have to open peace talks directly with the man responsible for the insurgents' battlefield ferocity. The rebel commander's characterisation of Nepal as dynamite between the two Asian giants was evidently intended to illuminate the firepower his lads and lasses still have. His broader point merits deeper introspection.

As a yam, Nepal was the perfect candidate for non-alignment. Our official middle-of-the-road line helped us weather the east-west ideological battles and the north-south geo-strategic rivalries. With periodic adjustments between equi-distance and equi-proximity, the yam metaphor made economic sense, too. Yellow American school buses, Soviet-aided tobacco industry, Indian-built railways and Chinese-designed roads coexisted. The end of the Cold War and the cooling of Sino-Indian tensions appeared to diminish our strategic importance. We were about to concede how multiparty democracy's second coming heralded the end of history when the Maoists sprang up.

Of late, the rebels are disheartened that a large section of Nepal's intelligentsia and political parties fail to recognise the disastrous ramifications of increasing hobnobbing with external powers. They draw our attention to the danger of Nepal being sucked into the vortex of a larger international conflict, which, they say, is impeding the search for a genuine political solution. The Maoists' own proclivities for linguistic legerdemain, however, preclude a full understanding of their cause. Comrade Badal, by continuing the tradition of pompous prose, does little to clear the clouds. It does contain enough powder to trigger a productive debate on our nationhood, if you're willing to concede that dynamite needn't always have a destructive connotation.

Small states always strive to chart their own course in turbid international waters. Some Pacific and Caribbean islands have become leading tax havens. Switzerland was synonymous with international diplomacy for decades before it decided to join the United Nations this year. Lebanon was emerging as the banking mecca of the Middle East before the prophets of doom prevailed in the mid-1970s. Al Jazeera TV has helped Qatar carve its own personality in a region awash in petrodollars.

True, we don't have that kind of affluence to make a difference. Building on Badal's assertion, we can draw the world's solemn attention and strategic assets. The overriding objective is to prevent the dynamite from exploding. Afghanistan encapsulates the perils of indifference to failing states. The idea that states too weak to secure their own territory could hardly represent a threat to the international order is antiquated. Proponents of defensive imperialism insist such places can provide a base for such non-state actors as drug, crime, or terrorist syndicates that may pose a danger to the world. An era of unpredictable threats puts great premium on pre-emptive action.

"Anticipatory self-defence" predates 9/11, though. A decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States continues to pour in billions to dismantle its nuclear arsenal. That initiative also involves keeping Russian, Ukrainian and Belarus scientists from working for rogue regimes. Through its nuclear programme, North Korea has succeeded in drawing humanitarian assistance from America, Japan and South Korea. Call it blackmail for greenbacks if you want, but it sure works.

Our strategy should rest on the time-tested reality that aid based on pure altruism belongs to the realm of idealism. The post-Second World War aid philosophy was guided by political-strategic goals. The decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall was spent on opening markets and minds to create and sustain a viable middle class. The post-9/11 objective is to eradicate poverty in order to prevent terrorism. The corollary should be our guiding philosophy. And we're getting the world's attention. The Belgian government almost collapsed over differences on how Nepal's conflict should be viewed. An opposition MP in Australia grilled Prime Minister John Howard for committing Australian lives to war against Iraq while ignoring mass terrorism in Nepal. Remember how British Prime Minister Tony Blair was accused of sneaking through parliament a decision to give us two Russian-built military helicopters under an aid programme normally used to bring peace to war-torn countries? (No wonder he couldn't spare time for Deuba last month). If it hadn't been for the Iraq crisis, the Blair cabinet could have ruptured over whether the land of the Gurkhas needed guns or reforms. You no longer have to be a cynic to expect our combustibility to deliver us from calamity.