Neat black solar panels gleam on sunny, windswept rooftops in this desolate country. Even as the government recently announced plans to electrify hundreds of Nepali villages using solar power, Phu gaon in Nepal's remote northwest is already a step ahead. "We first thought of having a hydropower project, but it turned out that electrifying the 33 households here through solar power would be cheaper," says Tashi Namgyal, chairman of Phu VDC.

Neat black solar panels gleam on sunny, windswept rooftops in this desolate country. Even as the government recently announced plans to electrify hundreds of Nepali villages using solar power, Phu gaon in Nepal's remote northwest is already a step ahead. "We first thought of having a hydropower project, but it turned out that electrifying the 33 households here through solar power would be cheaper," says Tashi Namgyal, chairman of Phu VDC. The gleam of solar-powered lights at night is the only indication of human habitation in this otherwise rugged and lonely terrain. After hours of trekking in the shadow of craggy cliffs interspersed with lush green juniper and pine forests, and guiding sturdy mountain ponies along narrow ridges, praying that they won't get spooked and kick us into the river rushing 300 ft below, we finally get our first glimpse of Phu.

From a distance, it is easy to miss the village perched atop a cliff, camouflaged by the rocky, barren surroundings. The original village, a walled city whose gates were kept closed against marauding invaders in the past, is falling to ruins. The few inhabitable homes remaining there are taken up by workmen from Rasuwa and Dhading who earn Rs 300 a day to build bridges, stupas, and homes just outside the old walls-tasks the locals don't have the time to do, occupied with keeping home and hearth together. The average Phu family owns about four or five dozen livestock, the products of which they barter for oil and flour with Mananges living lower down in Nyeshang Valley, a two-day walk away.

From a distance, it is easy to miss the village perched atop a cliff, camouflaged by the rocky, barren surroundings. The original village, a walled city whose gates were kept closed against marauding invaders in the past, is falling to ruins. The few inhabitable homes remaining there are taken up by workmen from Rasuwa and Dhading who earn Rs 300 a day to build bridges, stupas, and homes just outside the old walls-tasks the locals don't have the time to do, occupied with keeping home and hearth together. The average Phu family owns about four or five dozen livestock, the products of which they barter for oil and flour with Mananges living lower down in Nyeshang Valley, a two-day walk away. "People here are neither rich nor poor," explains the Tibetan Rimpoche at Tashi Lakang monastery. This monastery, the last of 108 monasteries said to be built by a renowned lama, is the reason that this remote outpost, a two-day walk from the Tibetan border, gets any visitors at all, in the form of devout Buddhists. Phu has 150 inhabitants, those who stayed back after the exodus of many from this village to the lower Nyeshang Valley, to take up houses abandoned by Mananges who have migrated to Kathmandu.

But as we lead our horses through the narrow, winding dirt path leading up to the village, there is little sign of life. Most Phu residents are up in the mountain pastures where they've taken their large herds of yak and sheep to graze. They spend days in tents and rudimentary stone sheds on these vast, open, windswept greens, churning butter in huge bags made from yak hide, shaking the bag back and forth up to 2,000 times for the desired butter.

But as we lead our horses through the narrow, winding dirt path leading up to the village, there is little sign of life. Most Phu residents are up in the mountain pastures where they've taken their large herds of yak and sheep to graze. They spend days in tents and rudimentary stone sheds on these vast, open, windswept greens, churning butter in huge bags made from yak hide, shaking the bag back and forth up to 2,000 times for the desired butter.  Fortunately, Tashi Namgyal is home. He has just returned from the pastures where he's left his livestock to graze. Namgyal is an educated man by Phu standards-about two dozen students attend the only primary school, while in Nar, the neighbouring valley, students from grades one to five are often lumped into one class as teachers play truant. Namgyal was unanimously appointed to the post by the villagers who offered him khadas and a bottle of local liquor. "In this part of Manang, it would be an offence to refuse such a decision," says Namgyal, who would rather be up in the pastures or carrying out household chores rather than being a local representative. "It's a lot of work and time. You have to commute between the district headquarters, be away from home. And there's not

Fortunately, Tashi Namgyal is home. He has just returned from the pastures where he's left his livestock to graze. Namgyal is an educated man by Phu standards-about two dozen students attend the only primary school, while in Nar, the neighbouring valley, students from grades one to five are often lumped into one class as teachers play truant. Namgyal was unanimously appointed to the post by the villagers who offered him khadas and a bottle of local liquor. "In this part of Manang, it would be an offence to refuse such a decision," says Namgyal, who would rather be up in the pastures or carrying out household chores rather than being a local representative. "It's a lot of work and time. You have to commute between the district headquarters, be away from home. And there's not much to gain."

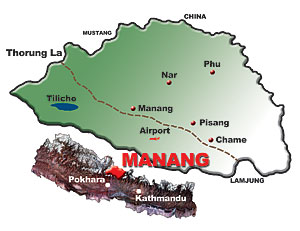

Even the government's announcement to open up Phu and neighbouring Nar to tourists appears to have not evoked too much enthusiasm in Tashi and his fellow villagers. In terms of distance, both Nar and Phu are an extremely long day's walk from Chame, Manang's district headquarters. But in terms of development and access, they are very, very remote. Apart from the odd researcher or a few climbing expeditions permitted to climb Himlung, Ranachuli and Gachikang, few foreigners have visited this former restricted area, and tourism infrastructure is non-existent.

Even the government's announcement to open up Phu and neighbouring Nar to tourists appears to have not evoked too much enthusiasm in Tashi and his fellow villagers. In terms of distance, both Nar and Phu are an extremely long day's walk from Chame, Manang's district headquarters. But in terms of development and access, they are very, very remote. Apart from the odd researcher or a few climbing expeditions permitted to climb Himlung, Ranachuli and Gachikang, few foreigners have visited this former restricted area, and tourism infrastructure is non-existent. The Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), which recently extended its network to include Nar and Phu, is preparing a suitable sustainable tourism development plan at the request of the government. They're looking at the possibility of developing restricted tourism similar to that in Upper Mustang. But there's concern that locals won't benefit from organised groups who porter in their supplies and spend little in the area, and tourism dollars don't find their way back to the community. "Another possibility is developing village tourism, like in Sirubari," says Narendra Lama, who runs ACAP in Manang. "There's still a long way to go," Lama says. "A lot of homework needs to be done, tourism infrastructure put in place, marketing carried out." A group of villagers from Nar and Phu will visit Annapurna Base Camp and Sirubari this autumn to see how tourism operates in these areas.

21 year-old Kursang Wangchu who runs the only lodge in Phu along with her cousin Tashi Khandu, would love to be part of that visit. She's says self-deprecatingly: "Our bhatti is so small. We don't even call it a hotel." Today, the one-room enterprise, complete with cooking hearth, two makeshift beds and roughly-hewn tables, serves both as a local bhatti and a lodge for the few weary travellers who find their way here. In winter, Kursang and the villagers of Phu descend to graze their livestock in Kyang (3,840 m), a crumbling settlement of old ruins set amidst sun-warmed meadows, once home to Khampa warriors on the run.

21 year-old Kursang Wangchu who runs the only lodge in Phu along with her cousin Tashi Khandu, would love to be part of that visit. She's says self-deprecatingly: "Our bhatti is so small. We don't even call it a hotel." Today, the one-room enterprise, complete with cooking hearth, two makeshift beds and roughly-hewn tables, serves both as a local bhatti and a lodge for the few weary travellers who find their way here. In winter, Kursang and the villagers of Phu descend to graze their livestock in Kyang (3,840 m), a crumbling settlement of old ruins set amidst sun-warmed meadows, once home to Khampa warriors on the run. About an hour's walk away, in the remains of a similar settlement called Chokho (3,753 m)-in summer a lush green valley abounding with wild garlic-the Narte, or people of Nar, descend from their village at 4,100 m just below the treacherous Kangla Pass (5200m), to graze their livestock. A gushing river serves as a boundary between the two villages that are bound by geography, culture, and marriage. Legend has it that a hunter from Nyeshang Valley shot a nawar or blue sheep, in the horn. He followed the nawar up into the mountains, where he came upon a field. The hunter sowed some wheat, promising himself that if it turned a ripe harvest, he would stay. Today, Nar Valley has a population of some 400 people who mostly depend on livestock for their livelihood.

All of this might change, and faster than we could imagine, if the instability along other trekking routes remains, and this other valley of Upper Manang becomes a magnet for people looking for something a little different, something remarkably untouched.