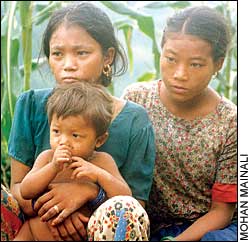

It is a steep two-hour uphill from the Prithvi Highway to Jogimara in Dhading district. And even from a distance, we can sense the stillness in the air. The village has only older people and children, they all wear a haunted look. They sit on their front porches, with shocked listlessness.

It is a steep two-hour uphill from the Prithvi Highway to Jogimara in Dhading district. And even from a distance, we can sense the stillness in the air. The village has only older people and children, they all wear a haunted look. They sit on their front porches, with shocked listlessness.

It has been nearly six months since 17 young men from Jogimara were killed while working on an airport runway at Kalikot in western Nepal. Their families don't have any tears left, but grief stillsears their hearts. Almost every family has lost a breadwinner, but no bodies were ever returned. There are 10 widows, 18 orphans and 14 bereaved parents at Jogimara.

Today, they are trapped between the need to come to terms with the deaths of their loved ones, a future of destitution and despair, and a government that calls them relatives of terrorists.

On 24 Feburary, 800 km away from home, the young men found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. Piecing together information from survivors, it is clear that the killing was a tragic combination of mistaken identity and other errors. And half-a-year later, this Dhading village is proof of the senselessness of the violence that has been unleashed on the Nepali people in the name of Maoism, and the callousness of officialdom.

In late November, just when the Maoists broke the truce and attacked the army in Dang, Jogimara's poorest of the poor were getting ready to go to Kalikot. They went because they trusted the sub-contractor, Kumar Thapa. They knew him, he had never cheated them, and he was even willing to pay an advance. And they needed the money. Of the 20 Jogimara men who left, only three returned alive. Among the dead were nine who were under 21 years old.

In late November, just when the Maoists broke the truce and attacked the army in Dang, Jogimara's poorest of the poor were getting ready to go to Kalikot. They went because they trusted the sub-contractor, Kumar Thapa. They knew him, he had never cheated them, and he was even willing to pay an advance. And they needed the money. Of the 20 Jogimara men who left, only three returned alive. Among the dead were nine who were under 21 years old.

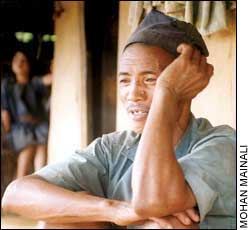

"More than the cold and the hardships, we were afraid of the Maoists," recalls Bel Bahadur BK from the original group. He returned home with two other villagers after a helicopter fired at the workers on 3 January. "We didn't want to die out there."  A month later, the Maoists attacked Mangalsen and Sanfebagar, killing 137 soldiers and policemen. The security forces went on a three-pronged hot pursuit northwards. The fleeing Maoists infiltrated the construction workers in Kalikot, and fired on an army helicopter flying overhead. Fearing army retaliation, the contractor told his men not to come to work and everyone had their identity papers ready in case the security forces came looking for Maoists.

A month later, the Maoists attacked Mangalsen and Sanfebagar, killing 137 soldiers and policemen. The security forces went on a three-pronged hot pursuit northwards. The fleeing Maoists infiltrated the construction workers in Kalikot, and fired on an army helicopter flying overhead. Fearing army retaliation, the contractor told his men not to come to work and everyone had their identity papers ready in case the security forces came looking for Maoists.

On 24 February, an army attack force stormed the quarters, thinking the workers were Maoists. According to eye-witness reports given to the National Human Rights Commission, 17 workers from Dhading, seven from Sindhupalchok, and 11 local villagers were killed. Among the villagers were the ward chairman from the Nepali Congress, two Sherpas from Solukhumbu who were working in Kalikot and two minors. Two workers from Sindhupalchok managed to survive. All the Maoists had fled by the time the soldiers arrived. That week, the Defence Ministry statement said 67 Maoists had been killed in encounters in Kalikot.  A senior army source told us that the security forces had reliable reports that the Kalikot area was where many of the Maoists who took part in the Mangalsen attack were hiding. "The Maoists had infiltrated the workers," he said. "But in hindsight, it is clear that the Maoists were provoking us to attack the workers and make it look like we were killing civilians." The survivors say that the Maoists had been coming around regularly to threaten them to stop work on the airport. They would refuse, but the Maoists would demand a meal, after which they would leave.

A senior army source told us that the security forces had reliable reports that the Kalikot area was where many of the Maoists who took part in the Mangalsen attack were hiding. "The Maoists had infiltrated the workers," he said. "But in hindsight, it is clear that the Maoists were provoking us to attack the workers and make it look like we were killing civilians." The survivors say that the Maoists had been coming around regularly to threaten them to stop work on the airport. They would refuse, but the Maoists would demand a meal, after which they would leave.

The fact that the Maoists shot at the helicopter using the workers as human shields bolsters the argument that the rebels were trying to trap the army into attacking civilians. But all this is of little consolation to the families, and it is clear that the attack in Kalikot was a colossal blunder. For the families of the dead in Dhading and Sindhupalchok, the wounds haven't healed with time. This is mainly because they never got the bodies of their loved ones. No one ever came to apologise or tell them that it was a mistake. And to make matters even worse, as far as the government is concerned, their sons and fathers were all "terrorists".  Dambar Bahadur Thapa lost his 17-year-old son. He says, "They were quiet kids, they never got into any trouble, they were just working hard to make some money to send back to their families." Gyan Bahadur Biswokarma lost two sons aged 30 and 25, and has only now decided to hold a funeral service for them. Shankha Bahadur Gurung lost two of his five sons, one 21 and the other 19. He had decided to go to Kalikot to see for himself after hearing the news, but the other villagers stopped him. Most other villagers have by now given up on their sons being alive, and are carrying out funerals on ritual pyres.

Dambar Bahadur Thapa lost his 17-year-old son. He says, "They were quiet kids, they never got into any trouble, they were just working hard to make some money to send back to their families." Gyan Bahadur Biswokarma lost two sons aged 30 and 25, and has only now decided to hold a funeral service for them. Shankha Bahadur Gurung lost two of his five sons, one 21 and the other 19. He had decided to go to Kalikot to see for himself after hearing the news, but the other villagers stopped him. Most other villagers have by now given up on their sons being alive, and are carrying out funerals on ritual pyres.

As the priest makes final preparations for Raj Kumar Shrestha's funeral, his mother is weeping loudly inside the house. Raj Kumar's wife Gita gave birth to a girl a month ago, but the baby died. His father Bel Bahadur is assisting the priest. "Console yourself," the priest mutters in between chants. "The dead don't come back no matter how much we want them to." That makes things worse, and the weeping is louder. Raj Kumar's five-year old son Amrit and his younger brother are playing marbles with a friend nearby, oblivious of what is going on.

"Three weeks after the incident there were rumours that they had been killed, another three months later the contractor called us to Kathmandu and gave us their wages," recalls Bel Bahadur. "It was then that we finally believed our son was dead." The private contractor also gave them Rs 3,300 each for funeral expenses. The government hasn't shown any such concern.

Eight of the dead are Praja families, and they still don't accept the deaths of their loved ones. They refuse to carry out the funeral rites, and hope against hope that their sons will one day appear. "Kumle had promised to come back by the mid-April, in time to help with sowing corn," says his mother Ninna Praja, tears welling up in her eyes. "We will wait for him forever, there was no reason for him to die."

Fourteen-year-old Govinda Praja lost his 60-year-old father Chitra Bahadur. "I still hope my father escaped, maybe he could have been delayed because of the difficulties of coming back," Govinda told us. "We had tried to discourage him from going so far away." However, Chitra Bahadur, decided to go because there was no work, his debt was piling up and he had no more cattle, goats or crops to sell. Govinda's mother Sukmaya is so torn by grief and worry that she hasn't spoken to anyone for months. In addition to his four little borthers and sisters, Govinda now also has to take care of his mother.

Two young teenage widows, Kaman Maya Praja and Syani Praja, still have terrified looks. They are living with their joint families, unsure of what lies ahead. Indra Bahadur Thapa lost his 16-year-old son, Gyan Bahadur in Kalikot. "Before leaving he had asked us to take good care of the cattle and not to borrow too much money," Indra Bahadur told us before looking away to wipe his tears. "He wanted earn enough to pay for his schooling."  It was only after the news of the death of innocents rocked parliament in March that Singha Darbar took notice. Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba told parliament on 6 March that the government was taking care to ensure that the innocent were not killed, and that if that happened, they would be adequately compensated. The Prime Minister's Office also set up a special committee headed by Rishikesh Gautam to hear and investigate complaints. When we contacted the committee for comment, its members were still unaware of the men from Jogimara who were killed in Kalikot.

It was only after the news of the death of innocents rocked parliament in March that Singha Darbar took notice. Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba told parliament on 6 March that the government was taking care to ensure that the innocent were not killed, and that if that happened, they would be adequately compensated. The Prime Minister's Office also set up a special committee headed by Rishikesh Gautam to hear and investigate complaints. When we contacted the committee for comment, its members were still unaware of the men from Jogimara who were killed in Kalikot.

Shree Kanta Regmi, secretary of the committee, told us that his office had not received any application from the families of the deceased. The bureaucracy's wheels don't start turning until a formal application is received, and Regmi told us that newspaper reports were not enough. "We will look into the cases as soon as we receive complaints," he assured us.

However, two former MPs, Prem Bahadur Singh and Rajendra Pandey, said that they have handed over the claims from the families of the dead to Gautam. The two also say that they personally informed the prime minister about the incident. The contractor who hired the workers, Subha Karki Nirman Sewa took the matter up with the National Human Rights Commission and the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal. But even the NHRC was not able to get help for the families, nor did it deem it necessary to conduct an independent investigation into the issue.

Shocking as the tragedy is, what is even more appalling for the families in Jogimara is the government's indifference to their plight. As we prepared to leave, one villager told us: "We've not just lost our children, but the government has branded them terrorists. Where is justice?"

(With additional reporting by Bhup Raj Khadka)

Killed in Kalikot  . Of the 17 killed in Jogimara, nine were under 21. The dead left 10 widows, 18 orphans, and 14 bereaved parents.

. Of the 17 killed in Jogimara, nine were under 21. The dead left 10 widows, 18 orphans, and 14 bereaved parents.

. Of the nine workers from Sindhupalchok, two survived.

. Eight villagers were killed, including the Nepali Congress ward chairman and two Sherpas from Solu Khumbu.

. Three others, including the sub-contractor, also died.

Names of the Jogimara dead, 17 from 15 families.

Chitra Bahadur Praja, Budha Bahadur Praja, Kumle Praja, Sher Bahadur Praja, Dilli Praja, Ram Bahadur Praja, Bikas Praja, Kanchha Praja, Gokarna Gurung, Tek Bahadur Gurung, Gokarna Thapa, Manju Thapa, Bhim Bahadur Thapa, Gyan Bahadur Thapa, Jhakka Bahadur Balchhane, Raj Kumar Shrestha, Raj Kumar Biswokarma, Tek Bahadur Biswokarma, Sanu Biswokarma and Bel Bahadur Biswokarma.