The woman had visited the health post with her sick baby. The health worker gave her some tablets and told her to give them to the child after meals. Two days later, the health worker asked her how the baby was doing. "I haven't been able to give her the medicine because you had told me to give it after food," the woman replied. "I have no food at home, and we haven't eaten for days."

The woman had visited the health post with her sick baby. The health worker gave her some tablets and told her to give them to the child after meals. Two days later, the health worker asked her how the baby was doing. "I haven't been able to give her the medicine because you had told me to give it after food," the woman replied. "I have no food at home, and we haven't eaten for days." The Maoist insurgency in western Nepal is taking its toll on the health of villagers, and the conflict is eroding many of the gains of the past decades in immunisation, maternal and child health. But the crisis goes beyond lack of medicines and vaccines: there is a danger of widespread malnutrition as the conflict makes food scarce, with repercussions on children and their mothers.

We were in Doti to organise a follow-up training of auxiliary midwives and staff nurses and also run a health clinic. (See "Women are dying in the far-west" by Aruna Uprety, #52). Thirty-five health workers from Accham and Doti were to take part. Only half of that number attended because they just didn't get the message. The phones are down, the postal service doesn't work, the buses don't ply.

And then the poignant question put to us by a nurse from Achham, for which we had no answer: "As a health worker, am I of any use in this situation? Most of my patients don't need medicines, they need food." The mule trains that traditionally transported food to Accham are stopped by both the security forces and the Maoists. "They should leave the locals alone," said one nurse. "We don't know what will happen when the potato and grains are exhausted."

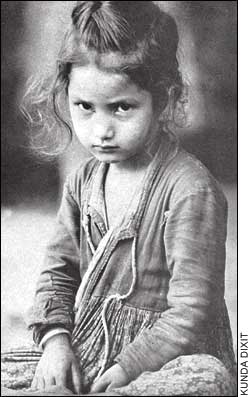

Most health workers say they will abandon their health posts once food supplies run out. They have no choice. This could create a humanitarian crisis in a region where services were poor even at the best of times. Even by Nepal's dismal human development standards, the west is the worst. The far-west has traditionally had the poorest maternal and infant mortality statistics in Nepal. The status of women in society is lower here than elsewhere, and female literacy is only nine percent. So, although no one is healthy here, the burden of disease tends to be heavier for women because of lack of access to health care. All this is now made much worse because of the conflict.

There is an epidemic of gynaecological problems, but either there is no health care, or the hospital is not accessible, or women hesitate to visit male doctors. But today, all these problems have been made far worse by the direct and indirect effects of the conflict. The one with the most serious implications for health is the food shortage, which is reaching crisis proportions. "Helicopters bring in food for government officials and security people, but there is nothing for us," says a midwife from Achham.

Among the women at the health camp is a woman who used to run an eatery last year at Mangalsen. "I closed it," she told us. "The Maoists kept asking for money, and the security people accused us of feeding the Maoists." It is the same story everywhere: as the conflict drags on, ordinary people like her are caught in the middle. Most of the time at the health clinic, we were counsellors and not doctors. Listening to the patients' problems with the lack of food for themselves and their children, all we could suggest were simple remedies and prevention methods.

Travel has become difficult and dangerous. There are checkpoints everywhere. There is no food, so you have to carry your own provisions. But there is no guarantee that your food won't be confiscated at a checkpoint. There are unofficial dawn to dusk curfews in every town, "unofficial" because it they aren't announced anywhere, news of them travels by word of mouth. Curfew violators are taken in, even shot. The lodge-owner in Doti warned us to eat and go to bed by 7PM. Outside there is a deep silence punctuated by a barking dog, and the rustle of leaves. There is "peace" here in far-western Nepal, but it is a deathly peace.

And as in all conflicts everywhere, it is the women and children who are most vulnerable. At last year's clinic in Doti, we were swamped with 2,000 patients. The VDCs had been mobilised to spread the word, and sick women came from surrounding districts, some walking or being carried for 10 hours. Others came all the way from Dailekh district, carrying their own food.

This time, with the VDC network all but non-existent, word of the camp couldn't get around. And even if it did, the difficulties of travel kept most sick women at home. The logistical difficulties in getting to us, and the lack of communications meant that we were able to treat less than 600, all people from nearby villages. It's not that there weren't more sick people-they just couldn't get to us. We brought back half our medicine supplies to Kathmandu because we could not dispense them to the sick and needy.

In the government's scheme of things, the security emergency takes precedence over medical emergencies. "We just pray to god that nothing happens to anyone at night when there is a curfew," says one social worker from Kailali, and adds with a hint of sarcasm in her voice: "No emergency is more urgent than the state of emergency."

(Dr Aruna Uprety is women's health and reproductive rights activist.)

(Dr Aruna Uprety is women's health and reproductive rights activist.)