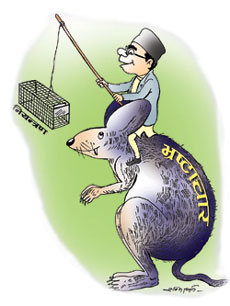

Parliament hurriedly passed two important anti-corruption bills on the last day of its 21st Session-one on Corruption Eradication, and the other on the powers of the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA).

Parliament hurriedly passed two important anti-corruption bills on the last day of its 21st Session-one on Corruption Eradication, and the other on the powers of the Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA). The two bills were in addition to two others that were presented at the Lower House in the last week of the winter session: one each on Special Courts and Impeachment Procedures. An all-party team was formed to rush these bills through-without enough time to listen to, let alone sort out, differences of opinion. Not surprisingly, the two anti-corruption bills were flawed when they arrived at the Upper House, and a number of amendments were proposed. Most of these were accepted by the Minister of State for Home Affairs in the Upper House. The amended Bills were sent to the Lower House on the last day of its sitting, but all the amendments from the Upper house were rejected.

Consider the following:

. Tipping a waiter at the Hyatt could be interpreted as corruption, punishable by three month's imprisonment.

. The house and land you've owned for years may be confiscated because the person from whom you bought it had in turn bought it from a person who engaged in an act of corruption 15 years ago.

. A government officer driving a government vehicle has an accident and causes damage worth Rs 5,000 but that too could be interpreted as an act of corruption attracting three months in jail.

. An employee of yours has been made to pay a bribe of Rs 100 to clear a consignment of calendars from the airport without your knowledge. You could get a three-month prison term for that.

. An ex-member of parliament does not return the government vehicle or vacate official residence but he can get away with a fine of Rs 5,000 and no jail term.

When the anti-corruption Bills receive the royal seal and become law each of the above become possible and the bills could have even more diverse and far-reaching ramifications.

The trouble begins with the definition of "public entity", which is spread across six subsections, each increasingly all-encompassing, from a private company to universities. The other problematic definition is that of a rastra sewak or a public servant-this would be anyone appointed, nominated or elected by His Majesty or the government or by any public entity, receiving or not receiving salary, allowance, remuneration, facility or status thereof.

The third and final definition which will create problems is that of "acts of corruption". There will now be restrictions on obtaining, without prior permission, any goods or services at discounted prices from anyone with whom a public servant has any dealing or could have in future. So, if a public servant seeks a discount or bargains while making a purchase for himself or for anyone, this could lead to a prison term of six to twelve months and confiscation of the goods bought. The law also prohibits, receiving for oneself or anyone else, any donation, gift or financial contributions. So if a public servant invites acquaintances for his daughter's wedding and guests bring presents, as is the custom, the official could face between three and six months in prison. Interestingly, if a public official receives Rs 1 million as a bribe or commission, the jail term is up to four years, receiving the same amount as a gift or donation gets you six months.

I had proposed that the scope of the term "public entity" be narrowed, to include only those entities fully owned or controlled by the government, or those in which it had at least one-third stake. I was accused of trying to keep the Nepal Bank Limited (NBL) out of the reach of law. I was also accused of trying to keep private organisations outside the purview of the CIAA. This is certainly how it should be. Even in the process of privatisation, ownership would pass from the hands of the government to the private sector. In such a situation, the private sector holding the majority ownership would ensure that there is no corruption and their methods would probably be more effective. We hear far more about corruption in government banks than in joint ventures. The authority to supervise and regulate banks irrespective of their ownership lies with the Nepal Rastra Bank. Handing over that responsibility to an agency that doesn't know much about banking isn't wise. Granting a loan without fixed-asset collateral, for instance, shouldn't automatically be an act of corruption, as is being implied by the agencies investigating corruption in the NBL and the RBB. This would be a major set back to commercial banking. These amendments were rejected by the Lower House.

The anti-corruption bills are very stringent in terms punishment, but not uniformly so. If a rastra sewak does not return a house, vehicle or physical asset, upon the expiry of his term, the maximum punishment is a fine of Rs 5,000. My suggestion, that the upper limit of the fine be increased to Rs 500,000, was rejected.

Another amendment that was rejected dealt with corruption in the revenue service. According to the Bill, any act which results in collection of lower revenue automatically becomes an act of the corruption. On this point, the Bill will discourage the acceptance of the documents, bills and invoices submitted by taxpayers under self-assessment. Our revenue policies have undergone radical reforms over the years moving towards self-assessment, under which taxpayer submissions are final in normal circumstances. Revenue reforms must continue and so I proposed an amendment suggesting that the acceptance of documents, bills and invoices submitted by taxpayers under the self-assessment policy will not be deemed an offence. Those who rejected this amendment misunderstood the self-assessment policy to be the Voluntary Disclosure of Income Scheme or the VDIS.

The section on rastra sewaks doing business also merited more cautious consideration. Anyone who is, or might in the future be, a public servant is prohibited from engaging or participating in business or contract or auction and from ownership or partnership in any firm or company or industry. Non-compliance is punishable by three to six months imprisonment and confiscation of wealth earned from the venture. I had proposed prohibition of such activity only if the intention was to benefit from the public post held to avoid conflict of interest. The change was voted down.

The Bill attempts to tackle corruption by making bosses-chief executives, general managers, members of boards of directors-accountable for the actions of subordinates. But this provision could easily be misused to frame organisational heads, by enticing or coercing low-level employees, so I suggested making them punishable only if the act was carried out with their knowledge. This, too, was rejected.

The wording of the CIAA bill on the confiscation of property earned by corrupt means is, again, flawed, impractical and unjust. The first part states that the property of a person found guilty of corruption would be confiscated irrespective of who legally owns it. Two UML MPs proposed that this clause be amended, but this was also rejected. Some MPs proposed an amendment clause barring anyone found guilty of corruption from contesting elections for five years. There are already laws in place that prohibit anyone found guilty of a criminal act or of moral degradation from contesting elections for six years but an act of corruption is not necessarily covered by that. This, too, was rejected.

The submission of wealth and property statements seems to be a main strategy adopted by the Bills to curb corruption. The efficacy of this is dubious, given the context of prevailing tax policies, and modes of sale and purchase of property. We have tax deduction at source (TDS) for income earned as salary, interest and from rentals, but documentary evidence of tax deducted is not provided to the income-earner.

If a system of providing proof of TDS is initiated, that may help in future but it may not be possible to furnish evidence of all income earned in the past, even legal income. We don't have a capital gains tax, so there's no way of proving income earned from sale of land, building or stocks. Our economy allows for many ways to hide wealth. Such provisions might simply fuel the black or parallel economy. Wealth declaration hasn't worked even in countries with more organised economies and tax systems. In our case, with the lack of confidentiality, it might just become another tool to harass political enemies.

The first version of the Bills contained a section imposing a statutory time limit of two years after retirement for a rastra sewak to be investigated and prosecuted. The Lower House removed this, exposing retired public officials to possible investigations for the rest of their lives. The experience of persons investigated by the CIAA show that such interrogations are punishing even if those accused are eventually found innocent. I suggested changing the statutory limit to six years, with a proviso to waive this if the charge was one that could result in imprisonment of more than five years. It was rejected.

Finally, I proposed an amendment to shield from prosecution all acts undertaken with good intentions. I was accused of trying to protect the corrupt. According to the Bills, in almost all cases malafide intention has to be proven to establish corruption. Of course it is important to deal strongly with those who engage in corruption, but it is equally vital to protect those who are not guilty.

Corruption results in bad governance, but good governance can only come about if rastra sewaks are encouraged and empowered to make the right decisions. Moreover, only a court can decide good or bad intentions behind an act. Also as it would be the responsibility of the prosecution to establish malafide intention, it would also be the responsibility of the defendant to establish bonafide intention. It cannot therefore be deemed as a loophole. This type of provision already exists in many of the other laws. Rejected.

Amendments are needed to remove the flaws in the anti-corruption acts. Prof Samuel P Huntington, in his book Political Order in Changing Societies says: "In a society where corruption is widespread the passage of strict laws against corruption serves only to multiply the opportunities for corruption."

(Dr Roop Jyoti is vice-chairman of the Jyoti Group and member of the Upper House.)