If Keshav Sthapith, mayor of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, had his way he would send out his bulldozers and demolish all the new concrete eyesores that have come up in his town.

If Keshav Sthapith, mayor of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, had his way he would send out his bulldozers and demolish all the new concrete eyesores that have come up in his town. His dream city is a mix of Kathmandu's medieval glory combined with the needs of a modern and cosmopolitan capital. When he has his mind set on something, naysayers better get out of the mayor's path. The way he sent bulldozers out to Tinkune and the Maitighar intersection two weeks before the SAARC Summit in January to create an impromptu mandala garden raised eyebrows in a country where nothing ever gets done.

Sthapith's critics-and there are many-point to the desolate and dusty Tinkune as a symbol of his failure. Others say he is a megalomaniac in the North Korean mould. In fact, the mayor is visiting Pyongyang next week for the birthday celebrations of Dear Leader Kim Il Sung. Obviously he will return with fresh inspiration.

We caught up with the mayor during one of his forays to the Valley rim. He points at the city below and tells us: "From here you see all that is still possible to do with Kathmandu. There is still enough greenery and open space in the Valley, and all we now need to do is manage future development properly."

thapith, whose name means "established" in Sanskrit, is passionate about the need to re-inject life into Kathmandu's dying bahals and resurrect the vibrant social life of the inner city. But he is also passionate about building a four-lane highway along the banks of the Dhobi Khola and Bishnumati to relieve the congestion in the city core.

Sthapith talks with feeling about his pet project, a special bicycle track from Maiti Ghar to the airport. But in the same breath he waxes eloquent about his plan for a megamall under Ratna Park, an entertainment centre like Sentosa Island in Balaju, and a shopping complex at Tinkune with underground parking and a huge figure of Manjushree on top.

Sthapith, at 42, looks like a man in a hurry. Technically he only has three months to go as mayor unless extended for a maximum of one year. "This was my probation period, I still have much to do," he says.

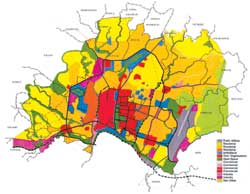

Sthapith's problem has been that he is from the Marxist-Leninist (M-L) faction of the CPN, which did not have a single seat in parliament and which recently re-merged with the main-opposition UML. National-level politicians find his style abrasive, and his high-profile populist projects in the capital a threat. Then there is a problem of jurisdiction. Kathmandu Valley is not a single administrative entity as the mayor would like it to be. It is a conglomeration of about 100 Village Development Committees and five municipalities. This makes it almost impossible to carry out effective planning of land use, zoning and transportation on a valley-wide scale.

But the mayor is doing what he can within the boundaries of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City. He has begun to enforce the strict building codes enacted 20 years ago and never really implemented. New settlements and housing schemes are now moving out into the suburban villages which is good because it spreads the economic activity around. What it isn't very effective in doing is imposing uniform land-use rules.

But the mayor is doing what he can within the boundaries of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City. He has begun to enforce the strict building codes enacted 20 years ago and never really implemented. New settlements and housing schemes are now moving out into the suburban villages which is good because it spreads the economic activity around. What it isn't very effective in doing is imposing uniform land-use rules. "The population density in the city core is too high," says Padma Sunder Joshi, National Program Manager of the Kathmandu Valley Mapping Project. But the trouble is that powerful people who have moved to new housing schemes on the city's outskirts, like Bhaisepati or Budanilkantha have sucked away government grants for infrastructure.

The mayor's office would like to go for infrastructure building through a more egalitarian land-pooling formula. After the successes of one such scheme at Naya Bazar, it has requests from communities seeking help. Land owners contribute a portion of their land which is collected and reallocated after taking some away for building roads, open spaces and meeting development costs.

There is some talk of creating an umbrella body to plan and oversee valley-wide land use, zoning and implementation in the form of a bill in parliament. However, local bodies fear the bill may just create another central-level bureaucracy.

Even if his future plans never materialise, Sthaphit has already done to Kathmandu what none of his predecessors have managed. A former engineering student, Sthapith took up his task by setting up a planning office which functioned almost independently of government bureaucracies that most other municipalities had inherited. He fought hard to keep this office even during the worst times as mayor, when bad blood after the UML-ML split caught the metro in the crossfire. This unit sketched some of his early plans-building parks at intersections, restoring medieval temples and patis and roping in the private sector to contribute money to his clean-up efforts.

The City Planning Commission, as it was known has now been replaced by the KVMP, which is supported by the European Union. It is this sprawling office at Tripureswor that helps Sthapith translate some of his dreams into GIS maps and action plans. And with technocrats taking care of implementation details, the mayor concentrates on fighting the larger political battles.

The City Planning Commission, as it was known has now been replaced by the KVMP, which is supported by the European Union. It is this sprawling office at Tripureswor that helps Sthapith translate some of his dreams into GIS maps and action plans. And with technocrats taking care of implementation details, the mayor concentrates on fighting the larger political battles. Sthapith can be a shrewd operator. When he had to convince Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba to clean up Tinkune before SAARC, he told him that demolishing houses in the city would take media attention away from the Maoist insurgency ahead of the summit. Deuba immediately saw the logic, and gave the go- ahead.

Sthapith's planners have a lot of projects on the drawing boards: land pool schemes on the banks of the Bishnumati and Bagmati, a road along the Dhobikhola, a pilot project to rejuvenate the city core, and another to see if Ghattekulo can be made more liveable. Then there are the high-profile plans to re-build Tinkune, landscaping the open space around the Rani Pokhari at Ratna Park, resettling squatters and, of course finding a permanent landfill site for the city's garbage.

Sthapit can be stubborn, and doesn't want to listen to those who don't agree with his plan of a shopping complex in Tinkune. Urban planners say the area should be converted into a park with tall trees and flowering bushes, as part of a green belt planned for the Ring Road.

Rani Pokhari, like Tinkune and Maitighar, was another difficult one to tackle because it had a fairly large number of stores that needed to be demolished amid growing political pressure. Sthapith was mourning his father's death when he was told that government had asked municipal officials to defer the demolition. He rushed to Rani Pokhari and personally led the charge with bulldozers.

"The home and local development ministers had asked to postpone demolition," he explained to us. "I knew it was now or never." Now he is under pressure to rebuild, largely because the project is very visible. The plan is to make a leafy park, get rid of the ugly iron railing around the pond and give a Rani Pokhari Park across the road from Ratna Park back to the city. The negotiation to demolish some of the blocks of Tri-Chandra campus north of Rani Pokhari is proving more difficult. Sthapit's plan to move the college to the former cement factory at Chobhar is meeting stiff resistance.

"The home and local development ministers had asked to postpone demolition," he explained to us. "I knew it was now or never." Now he is under pressure to rebuild, largely because the project is very visible. The plan is to make a leafy park, get rid of the ugly iron railing around the pond and give a Rani Pokhari Park across the road from Ratna Park back to the city. The negotiation to demolish some of the blocks of Tri-Chandra campus north of Rani Pokhari is proving more difficult. Sthapit's plan to move the college to the former cement factory at Chobhar is meeting stiff resistance. The mayor says money is not an issue when it comes to doing things that matter. With land pooling for housing, private-public partnerships to maintain traffic triangles real estate values rise as neighbourhoods get developed and gentrified and everyone benefits. "I see myself only as a facilitator of progress," says Sthapith modestly. "Once people believe I am not siphoning away their money they come and participate in the projects without me telling them what to do."

The dreamer in Sthapith takes over every time he's on his own, and he says his life's work will not stop with Kathmandu. If given the chance, he wants to launch a job-creation campaign for Nepalis that could remove the frustrations of unemployed youth that lie at the root of the Maoist insurgency.

Besides being mayor, Sthapith is also an amateur poet and has to be restrained from bursting into verse at inauguration ceremonies. He dabbled in tai-chi, but gave up after he was unable to maintain a training schedule. Now, he's learning the fearful Kal Bhairab dance. He finds the vigorous traditional dance routine strenuous, but a great stress-reliever. Don't be surprised one of these days to see our mayor alighting from his olive-green Mercedes Benz to try out a few twirls near one of his recently-beautified traffic islands.