Remember those National Geographic specials where bearded scientists whispered, stooping over creepy crawly life forms thriving on bat guano in caves below Borneo's jungles? You can do that right here in Kathmandu Valley.

Remember those National Geographic specials where bearded scientists whispered, stooping over creepy crawly life forms thriving on bat guano in caves below Borneo's jungles? You can do that right here in Kathmandu Valley. Chobar, best known for its defunct cement factory, is where Manjushree is said to have drained the Valley's ancient waters with a swoop of his sword. It is also home to a vast network of underground tunnels. The womb-like subterranean passages have long served as playgrounds for village children, rent-free storage space for smugglers and dim rendezvous spots for amorous adventures. Now they are a haunt for amateur spelunkers.

But even the most determined caver should think twice about venturing alone into the eternal night below. The caves are full of hazards, not least, the danger of getting in too deep and not finding a way back out. A careless misstep could deliver you to a bottomless depth and an inattentive movement could mean a skull cracked against one of the innumerable, silent rock bulges. If ever you venture down, try throwing a rock into one of those dark pits and wait for the sound of the rock hitting bottom. You won't hear it.

The caves are also home to a shadowy lake revered by village folk as Chakun Tirtha, and even local experts haven't figured out its perimeters yet. Some of the rock projections that endanger human life and limb are worshipped as manifestations of Shiva. In days bygone, devotees bravely ventured inside every full moon of the first month of the lunar Nepali calendar and performed pujas. This practice has been abandoned for some time, but there remains evidence of pujas past on many stalagmites and stalactites. There are even rumours of a football field-sized space somewhere deep below, of smuggler's forgotten treasures and buried one-eyed Rudrakshas, the sacred seeds of Shiva.

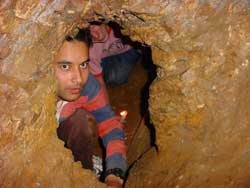

Before you dreaming about rescuing lost treasures be warned: even with help, you need great determination and concentration to make your way safely in and back out. The caves are not one long passageway, but a complicated network of child-sized tunnels leading along a plummeting, zig-zagging subterranean crawl. No one has even managed to explore the caves thoroughly enough to determine their exact depths and dimensions.

Before you dreaming about rescuing lost treasures be warned: even with help, you need great determination and concentration to make your way safely in and back out. The caves are not one long passageway, but a complicated network of child-sized tunnels leading along a plummeting, zig-zagging subterranean crawl. No one has even managed to explore the caves thoroughly enough to determine their exact depths and dimensions. There are dozens of entrances to the caves scattered around Chobar, the most prominent is atop the hill overlooking Jala Binayak. Chobar elders say the caves lead out as far as Patan, Swoyambhu and even Panchkhal in the east-though they strongly discourage village children from verifying these claims on trips below. Some young Chobar residents, including a disco bouncer and caving entrepreneur named Ravi Lama, have set out to defy their elders and make a name for themselves as the caves' in-house experts.

"These have been our playgrounds since we were little," says Ravi. "Every time we emerged, we'd have to wear our clothes inside out so no one would notice how dusty we were and scold us for going in." Ravi and his friends Prasun Thapa Magar, Umesh Manandhar, Roshan Shrestha and Chiranjiwi Nepal have joined together to explore the dark spaces of the rocky earth, and their twisting and squeezing around have transformed them from boyish miscreants to tourist guides. "We want to act as guides for any Nepali or foreigner wanting to visit these caves and make it our full-time profession," says Prasun.

Despite the modest success of their caving (ad)venture thus far, they still face opposition from village elders who look down on the idea of crawling through rocky spots to earn a living. "Why do you need to go in there?" scolds Ravi's grandmother as he emerges with a tour group. "Why don't you do something more productive?"

That is just what they are out to prove-that the caves can indeed be productive, and even productive.

(To go spelunking in Chobar, contact Prasun at 331069.)