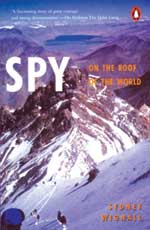

Spy on the Roof of the World

Sydney Wignall

Penguin Books India 2002

Price: Rs 495  By the light of a flickering candle stub I wrote up my diary of the day's events, to wit the intensive interrogation I had been subjected to.One of my interrogators spoke passable English. I and my companions in incarceration, John Harrop and Damodar Narayan Suwal, called him \'Smoothy' because of his oily, unctuous manner. I sat up in my quadruple-layered down-filled sleeping bag. It was identical to those used on the ascent of Mt Everest two years earlier. That bag should have kept me warm, but the temperature inside my unheated mud-walled prison cell often dropped to 20 below and rarely rose above freezing point, and most nights I shivered and slept badly. Occasionally I had to visit the lavatory in our prison yard, which consisted of a couple of deep holes dug into the hard ground. I would climb out of my bag, put on my boots, walk bent double to the cell door (because the ceiling of my cell was so low I could not stand upright), knock hard, and eventually a Chinese guard, clad in khaki quilted jacket and trousers with a padded greatcoat on top would open the cell door and conduct me to the prison's primitive thunder hole. At all times the guard would keep his 7.65 mm PPSh assault rifle pointed at me.

By the light of a flickering candle stub I wrote up my diary of the day's events, to wit the intensive interrogation I had been subjected to.One of my interrogators spoke passable English. I and my companions in incarceration, John Harrop and Damodar Narayan Suwal, called him \'Smoothy' because of his oily, unctuous manner. I sat up in my quadruple-layered down-filled sleeping bag. It was identical to those used on the ascent of Mt Everest two years earlier. That bag should have kept me warm, but the temperature inside my unheated mud-walled prison cell often dropped to 20 below and rarely rose above freezing point, and most nights I shivered and slept badly. Occasionally I had to visit the lavatory in our prison yard, which consisted of a couple of deep holes dug into the hard ground. I would climb out of my bag, put on my boots, walk bent double to the cell door (because the ceiling of my cell was so low I could not stand upright), knock hard, and eventually a Chinese guard, clad in khaki quilted jacket and trousers with a padded greatcoat on top would open the cell door and conduct me to the prison's primitive thunder hole. At all times the guard would keep his 7.65 mm PPSh assault rifle pointed at me.

Harrop Damodar and I regarded toilet paper as the one facet of civilised society we greatly missed. I decided to tell Smoothy at my next Thought Reform Session that I had used all the toilet paper for the abstersion of my fundament. In the meantime, after completing my notes on the day's interrogation session, I duly rolled up a thin sheet of paper and pushed it down the inflation tube of the pillow of my inflatable mattress. The diary was written not just in toilet paper, but also on chocolate wrappers and also our Chinese guards' cast-away cigarette packets. I was eventually to take it with me, out of Tibet, after my release from imprisonment.

Sometime in the night, I was conscious of something warm on my forehead. I switched on my torch, and shone the beam onto my head I could espy a ball of black wool on the mouth of Megan, a good Welsh name. Megan was a pregnant Tibetan snub-nosed tail-less rodent, and she had entered my bag while I was asleep bitten into my woollen sweater and retreating into my forehead was in the process of winding in wool, rotating it in her mouth, for the nest she was preparing for her offspring...

I couldn't get back to sleep. The wind was getting up and we were now deep into winter. All the passes to the South into Nepal and India, were closed until the spring. I shivered. "Christ, if they ever let us go, how the hell will we get back over the top in winter?"

Wignall, Harrop and Damodar trek back into Nepal after being freed by the Chinese. After traversing the Urai Lekh in winter, they descend to the wild gorge of the Seti River.

The ground became steeper and the track narrower, as we climbed away from the Seti River bed. There was a huge rock overhang just beyond the gully facing us, and icicles ten to fifteen feet in length hung from it, poised over an ice bulge. Ice walls are one thing, but ice bulges are another. One of the main principles of rock and ice climbing is to maintain correct posture, and thus ensure safe balance. With an ice face two to three feet from one's chin, one can stand upright in footholds, and hold oneself in a vertical position by placing hand or ice axe against the face. But ice bulges demand chipped-out footsteps, and no face to balance against. The trick is not to lean in towards the face, for if you do, your feet are prone to shoot out into space.

Harrop ducked under the icicles, leaving a perfect set of cut steps behind him for Damodar and me. Then he was onto the ice bulge, and Damodar and I watched, unable to offer any assistance, as Harrop gradually chipped his way round the corner out of sight. Then we heard his voice. "Back on the track again."

Damodar and I let out a cheer, for the delay caused in cutting steps across those two gullies had taken more than half an hour of our precious daylight. I heard Harrop, out of sight now, chipping away with his axe, and below the ice bulge I saw the ice flakes he was cutting out, sparkling and tinkling down the gully wall, until they vanished from view.

Harrop was waiting round that corner ready to give advice. If any one of us slipped, there was nothing the other two could do to arrest his fall. We were back on the track for a hundred yards or so, just flat rocks placed on top of saplings jammed into crevices and cracks on the cliff face. Ahead lay another section of vanished track. We were back cutting steps in the ice. Midway across this section, the angle eased in a shallow snow-filled gully. There was danger here.

Gingerly kicking steps in the snow, standing straight upright, ice axe held almost horizontal against the snow face, Harrop worked his way quickly across, to be followed by Damodar, with me in the rear. I took a lower line than Harrop and Damodar, with the intention of not making too deep a single line of steps across that snow slab. I made it with a sigh of relief, but no sooner had I reached a rock stance on the far wall of the gully, than I heard a rushing-swishing sound, and looking behind me, I watched a thousand tons or so of snow avalanche clown that gully, until it vanished over an overhang. If any one of us had been in the middle of that snow slide, he would have gone down into the river Seti, more than a thousand feet below. I followed Damodar, and across another gully I could see Harrop chipping steps round another of those interminable bloody corners.