The big issue dominating national politics this week and next will be whether or not the state of national emergency is going to be extended after its 22 February deadline. Parliament must endorse the emergency by a two-thirds majority for it to be extended by another three months, otherwise it will automatically lapse.

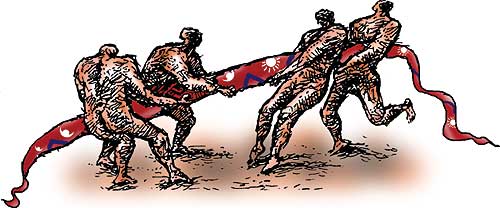

The ruling Nepali Congress would like it endorsed, but the dissident faction within it led by Girija Prasad Koirala is bent on giving Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba as hard a time as possible. The main opposition UML, euphoric about its impending reunion with the ML, will need to show a token of its opposition status by throwing a tantrum. The UML holds the swing vote in parliamentary arithmetic, and (rhetoric notwithstanding) will be expected to extract its pound of flesh for letting the extension sail through. They will probably boycott the session and thereby support the extension while seeming to be opposed to it.

The Maoists, for their part, also favour an extension since it shows them to be at par with the Royal Nepal Army, and a force to be reckoned with. The comrades know that the longer the emergency drags on the better it is for the cause. Their call for a national strike on 22-23 February is aimed at keeping the populace in a state of panic. Time, after all, is on their side, whereas the army wants to have this thing wrapped up quickly one way or other.

But this entire debate on whether or not to extend the emergency is getting to be a fairly academic exercise. Either way the country is facing an emergency situation. We have an economic emergency, a fiscal emergency, an emergency of capital flight, a development emergency, we have emergencies in export and tourism.

Many people had different expectations of the emergency when it was declared on 26 November. Some thought it would be like Indira Gandhi's emergency: civil servants would go to office on time and there would be a crackdown on corruption. But the government seems to think the emergency has absolved it from action. "The soldiers are taking care of things, we'll sit back and relax," seems to be the motto. Well, as it turns out, all the emergency did was spook tourists, muzzle the media, and make the civilian leadership extinct in large parts of the country. In fact, except for the capital and the district headquarters, there is no sign of government anywhere else. The Maoists would be foolish not to step into this vacuum.

The lesson of the past 90 days is clear: if the government is serious about countering the Maoists, then its military campaign must go hand-in-hand with a drive to bring the people on its side. This hasn't happened so far. The war will not be won by alienating the citizenry and curtailing their rights.

As the army carries out its cordon-and-destroy operations on Maoist hideouts with increasing effect, there is little sign of a government machinery being mobilised to deliver the goods in liberated areas. If the extension of the emergency means an extension of this state of affairs, then it does not matter that the emergency is extended.

We don't know how else to put this. Nepal is facing an unprecedented crisis. There is a deep sense of foreboding that something is going to give. The leadership is oblivious: bickering in the back rooms, threatening signature campaigns, back-stabbing, horse-trading, and all the other shenanigans of a mutiny-minded cabinet. In short, everyone in the game is carrying on as they have for the past 12 years: which is what brought us to the present crisis.

For once, can we have a prime minister who is less worried about the magic number 57 and more concerned about the country's long-term development? Can we have dissidents within his party less focussed on unseating him and more on working with him to resolve the crisis? Can we have an opposition not gloating at the sight of a squirming government, and pondering that a similar fate awaits it when they come to power?

If this infighting carries on for much longer, there will be nothing left to fight over.