Perhaps there was really no doubt that this SAARC Summit would ultimately go ahead. Perhaps all the sabre-rattling of the past weeks between India and Pakistan was in fact carefully calibrated brinkmanship to make this summit happen.

Perhaps there was really no doubt that this SAARC Summit would ultimately go ahead. Perhaps all the sabre-rattling of the past weeks between India and Pakistan was in fact carefully calibrated brinkmanship to make this summit happen. Whatever the case, the two South Asian nations nearly went to war over the 13 December suicide attack on Parliament in New Delhi. They have now stepped back from the brink. Will Kathmandu be where they patch up? More importantly: will Kathmandu be where they will find some mechanism to prevent a risky escalation like this in future?

Not likely, say experts and officials from the region who have gathered in Kathmandu this week prior to the Summit. "We shouldn't be too ambitious," one senior South Asian diplomat told us, "The fact that the Summit is taking place is already a miracle." Indian and Pakistani officials are coy about the question on everyone's lips: will Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and General Pervez Musharraf shake hands in front of the television cameras after the Nagarkot retreat? "Let's wait and see," is all they say.

As the tit-for-tat cancellations of trains, over-flights and satellite transmissions show, things can get pretty petty between New Delhi and Islamabad. Even in Kathmandu, organisers said, there was at least one request for a change in seating arrangements by one of the countries which didn't want to sit next to another. Ironically, participants said the atmosphere during the preparatory meetings was one of surprising friendship and camaraderie. "Outside they are about to go to war, inside they are best of friends," one Nepali participants told us. "We have Pakistan seconding Indian proposals and the other way round. Despite everything everyone wants SAARC."

By all accounts, the draft declaration of the Summit and other conventions have seen surprisingly smooth sailing through the committees. "There are no hitches, no needlessly long debates about commas and brackets that we saw in previous summits," another delegate told us. The reason could be that everyone wants this on-again-off-again Summit to go without a hitch.

The meetings discussed giving the 1987 SAARC anti-terrorism convention more teeth by making it compatible with national laws, and agreed with provisions of post-11 September United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373. But what if one nation's terrorist is another's freedom fighter? The answer from one delegate: "We did not go into definitions."

Officials in the preparatory meetings also agreed on deadlines: having the SAFTA framework treaty ready by end-2002, re-starting SAARC meetings at different levels to keep dialogue open. More could happen by the time we reach the Summit because everyone, including leaders, seem to be under a lot of pressure to show that SAARC works.

"The timing may have worked perfectly for all because despite tension, the Summit provided an opening," says Sridhar Khatri, executive director of the Institute of Foreign Affairs in Kathmandu. "It looks like Churchill's jaw-jaw being better than war-war is at work inside the closed doors."

There is little doubt that the entire spotlight during this summit is going to be on Vajpayee and Musharraf. In fact, their every gesture and eye contact (if not shoulder contact) is going to be minutely recorded for signs of thaw. The danger is that the media glare in Kathmandu may tempt both to play to the domestic galleries. But for SAARC's sake, everyone is hoping for a truce.

Sixteen years of SAARC have made not just the leaders of India and Pakistan, but the smaller countries as well guilty enough to at least show they can meet during these annual summits-even if it is just to deliver speeches. This time, the added complication was India's ban on overflights by Pakistan International Airlines which forced Gen Musharraf to take a round-about route via China. India denied it is being petty, one senior Indian diplomat told us: "We have taken terrorism for so long, we just had to draw the line." But Pakistani officials say they have gone out of their way to assuage India on terrorism. "There is real mistrust. They don't want to believe we are acting in good faith," said one.

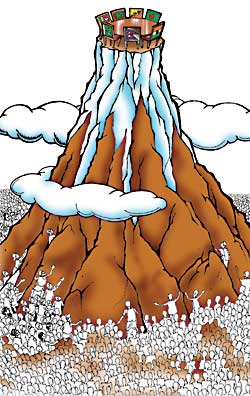

Former SAARC Secretary General, Nepali diplomat Yadav Kant Silwal saying most of this is posturing. He is a true-blue believer in SAARC: "This is the only answer to South Asia's troubles. There is no other road." But going on this road has been painfully slow, and SAARC appears to need new vision and commitment if it is survive its self-inflicted injuries. Kathmandu should mark the beginning of this process.